Two lifeforms merge into one organism for first time in a billion years

‘The first time it happened, it gave rise to all complex life,’ scientists say

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

For the first time in at least a billion years, two lifeforms have merged into a single organism.

The process, called primary endosymbiosis, has only happened twice in the history of the Earth, with the first time giving rise to all complex life as we know it through mitochondria. The second time that it happened saw the emergence of plants.

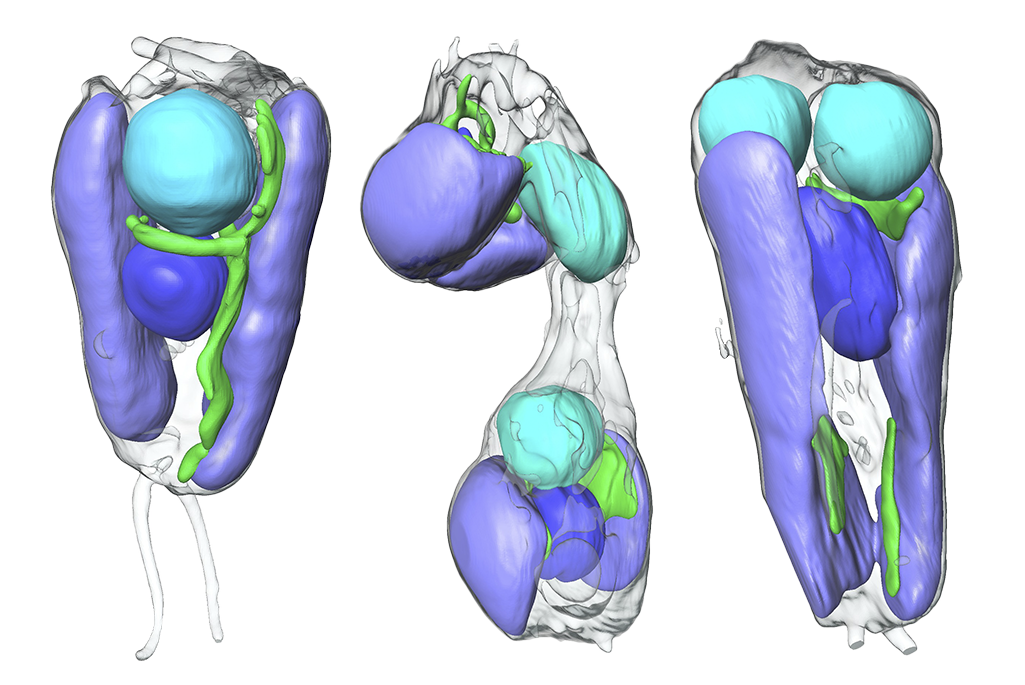

Now, an international team of scientists have observed the evolutionary event happening between a species of algae commonly found in the ocean and a bacterium.

“The first time we think it happened, it gave rise to all complex life,” said Tyler Coale, a postdoctoral researcher at University of California, Santa Cruz, who led the research on one of two recent studies that uncovered the phenomenon.

“Everything more complicated than a bacterial cell owes its existence to that event. A billion years ago or so, it happened again with the chloroplast, and that gave us plants.”

The process involves the algae engulfing the bacterium and providing it with nutrients, energy and protection in return for functions that it could not previously perform – in this instance, the ability to “fix” nitrogen from the air.

The algae then incorporates the bacterium as an internal organ called an organelle, which becomes vital to the host’s ability to function.

The researchers from the US and Japan who made the discovery said it will offer new insights into the process of evolution, while also holding the potential to fundamentally change agriculture.

“This system is a new perspective on nitrogen fixation, and it might provide clues into how such an organelle could be engineered into crop plants,” said Dr Coale.

The papers detailing the research were published in the scientific journals Science and Cell.

The scientists involved came from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), the University of Rhode Island, the University of California, San Francisco, UC Santa Cruz, the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Institut de Ciències del Mar in Barcelona, National Taiwan Ocean University, and Kochi University in Japan.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments