After years of trying, scientists finally find our sense of direction

Our internal compass is in the brain's entorhinal complex

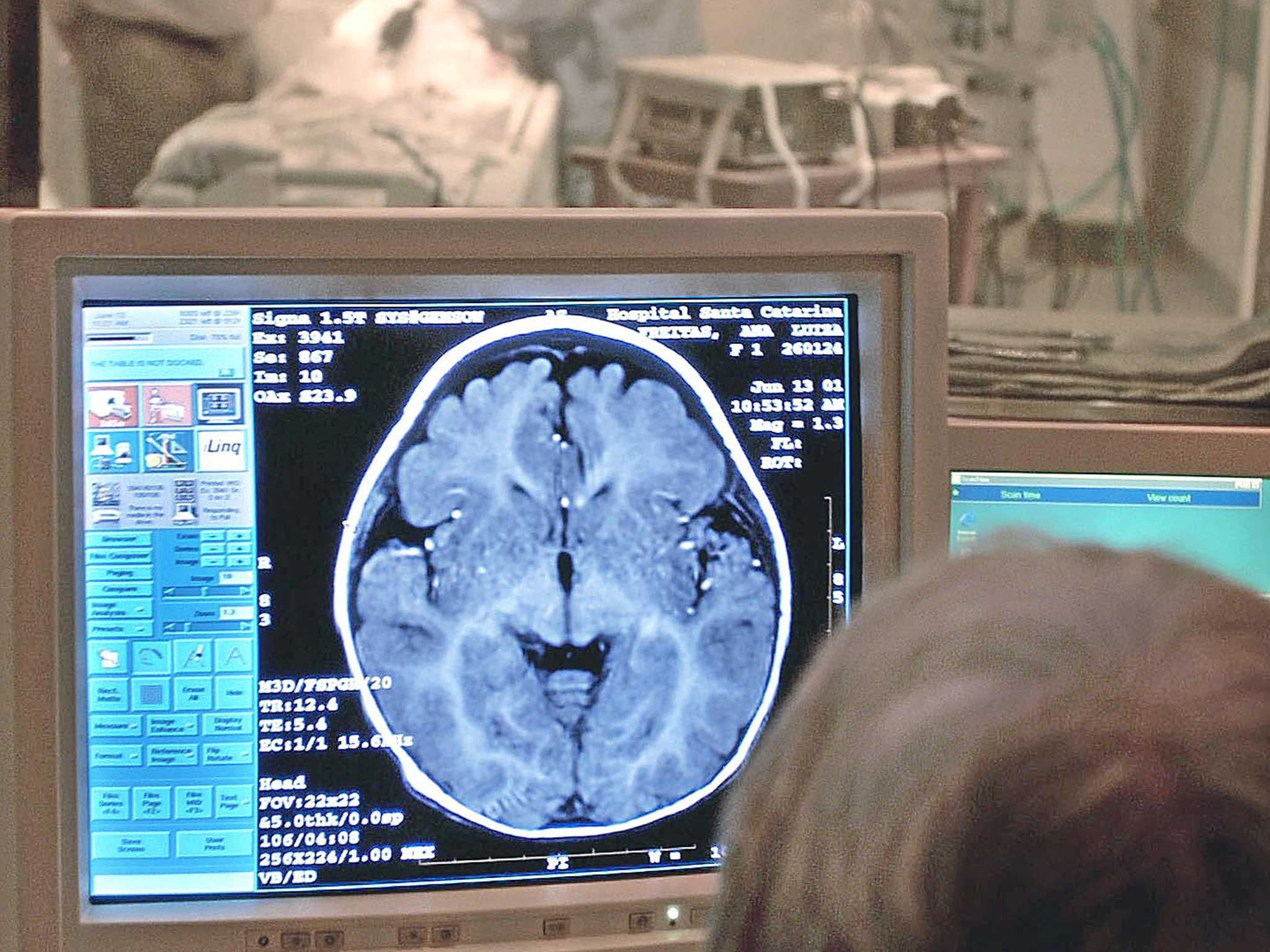

The internal compass of the brain that tells you the direction to go in order to reach your final destination has been found by scientists using an MRI machine that measures nerve activity inside the head.

Researchers have found that a brain region known as the entorhinal complex is responsible for making the key calculations of how to navigate from one place to another – a critical feature of a person’s sense of direction.

Tests on 16 healthy volunteers, who were asked to navigate around a simple “virtual” environment on a computer screen, revealed that the entorhinal region became significantly more active than other brain regions, according to a study published in the journal Current Biology.

“This type of homing signal has been thought to exist for many years, but until now it has remained purely speculation,” said Hugo Spiers of University College London, who led the study.

“In this simple test, we were looking to see which areas of the brain were active when participants were considering different directions,” Dr Spiers said.

“We were surprised to see that the strength and consistency of brain signals from the entorhinal region noticeably influenced people's performance in such a basic task,” he said.

The entorhinal region is one of the first parts of the brain affected by Alzheimer's disease, so the findings may help to explain why people start to get lost in the early stages of the disease, the researchers said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments