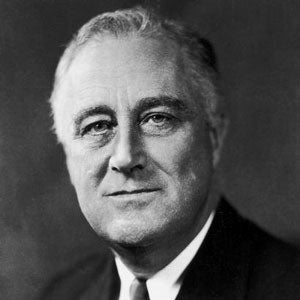

Franklin D Roosevelt: The man who conquered fear

32nd president - 1933-1945

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.

Americans celebrate Franklin D Roosevelt as the president who led them out of the Great Depression of the 1930s and through the greatest global conflict in history. He ranks alongside Jefferson, Lincoln and Wilson as an architect of dramatic change in his own society. For all his famous informality of manner, he was perhaps the most regal leader the United States has ever had, revelling in the exercise of executive power. From his first day in the White House, he showed himself undaunted by any challenge. He pursued a vision of social justice, and of restraint upon the unbridled capitalism of America's previous century, which was perceived as revolutionary, although he never addressed the great evil of racial segregation.

Today, as the world faces an economic crisis that some believe is as grave as that of the Thirties, Roosevelt's record in office is scanned and weighed by modern politicians, to discover whether his example has anything to teach them about how to climb back from the pit. The words of his inauguration speech on 4 March 1933 once more echo around the world: "The only thing we have to fear is fear itself – nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror that paralyses needed efforts to convert retreat into advance."

When he took office, nearly a third of America's workforce was unemployed. Many banks were closed and tottering on the brink of collapse. Business confidence was broken, the nation was rudderless. At his death, the US was the richest and most powerful nation on Earth, the position it has held ever since. Few historians doubt that Roosevelt deserves a large part of the credit for this achievement. Although some of his policies remain shrouded in controversy, he mobilised the American genius in a way few of its leaders have matched, either in peace or war.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt was born into the hereditary aristocracy of upstate New York, the inheritor of 17th-century Dutch immigrants whose descendants had ever since been growing a fortune based upon land speculation. His father, James, was a 52-year-old widower with one son when he married 26-year-old Sara Delano, whose family had made their own pile in the China trade. Franklin was born on 30 January 1882 at the Roosevelts' Springwood estate, beside the Hudson river at Hyde Park. He became his mother's adored only child. The family lived the lives of country gentry, surrounded by servants and estate workers. James repeatedly declined offers of public office, or indeed of any employment. He took his son on long summer trips to Europe and at home trained him to inspect herds, cherish trees and confine social exchanges to his own kind. The Roosevelts were famously snobbish.

Franklin was tutored at home until he was 14, then taken in his father's private railroad car to enrol at the exclusive Groton school, before moving on to Harvard. The boy had no contact with mainstream America, very little with its cities, and none with hardship. He sailed his own 21ft boat, collected stamps, shot birds that were then stuffed and mounted by a local taxidermist, and read voraciously and retentively. His social life was restricted to a tiny circle of those whom Sara deemed acceptable. In a letter home, he offered consolation for James's distress at losing his butler: "Don't let Papa worry about it, after all there are plenty of good butlers in the world." A lofty observation from a teenager of any social class.

He loved school, became a star debater, and displayed an early inclination towards a political life. He showed a hostility towards imperialism that would stick: "Hurrah for the Boers! I entirely sympathise with them." At university, he edited the Harvard Crimson, and joined all the "right" societies. Though his parents were committed Democrats, as was Franklin himself, his role model was his Republican cousin, Theodore, who became President in 1901. The young student's unfailing geniality made him popular enough, but there were those who found him, in the words of one classmate, "bumptious, cocky, conceited". How could a young man gifted with good looks, wealth and high intelligence be anything else?

On a trip to England in 1903, he flirted enthusiastically with every pretty girl he met at country house parties. Soon after his return to New York, he fell in love with his cousin Eleanor, the orphan niece of Theodore. The couple were married in March 1905, the bride being given away by the President. Sara presented them with a New York City town house, though Franklin was still attending Harvard Law School. On his graduation, he became a clerk with a New York law firm, though it was already plain that his ambitions were focused on political office.

Sara, who had become a widow when James died in 1900, still dominated her son's life and controlled the purse strings, to the deep and enduring resentment of Eleanor. When an upstate Democrat power-broker offered to help the gilded youth to a state senate seat in 1909, the man paused outside the local bank, where the party faithful were gathered to meet him, and said: "The men looking out of that window are waiting for your answer. They won't like to hear that you had to ask your mother." Roosevelt agreed to run.

For the first time in his life, on the campaign stump he began to encounter ordinary Americans. He met a house painter working at his half-brother's house who doffed his cap and said: "How do you do, Mr Roosevelt." The painter was a Democratic committee man. The candidate said: "No, call me Franklin. I'm going to call you Tom." He displayed a gift that he would retain for a semblance of instant intimacy with everybody he met. This masked a dislike for showing his hand, or revealing his real thoughts or intentions. Roosevelt was always a plausible liar, especially about his own and his family's achievements.

In this first election, he stormed home in a traditionally Republican area. As a freshman senator up at the state capital, Albany, instead of learning the ropes he plunged into hostilities with the New York City bosses of Tammany Hall. "There's nothing I love as much as a good fight," he told The New York Times. He lost his first battle with Tammany, as a would-be reformer.

Yet some of his contemporaries thought him a prig and hypocrite. He showed little interest when Frances Perkins, the pioneer campaigner for workers' rights, sought to enlist his aid. As a state senator, the only pitch for which he was later remembered was his fight against logging in local forests – he had a lifelong passion for trees.

Always vulnerable to infections, he was suffering from typhoid when he came up for re-election in 1912. He enlisted the aid of a tough political fixer, Louis Howe, to run his campaign – and won again. A few months later, to the anger of some of his constituents, he abandoned Albany for Washington.

At the age of 30, he was offered the plum post of assistant secretary of the US Navy. He held the post for seven years, among the happiest of his life. His superior, Josephus Daniels, was an ineffectual figure who proved happy to let Roosevelt have his head. His young assistant proved a whirlwind of energy and enthusiasm. "I now find my vocation combined with my avocation in a delightful way," Franklin wrote. His growing reputation survived such embarrassments as an interview given by the incorrigibly grand Eleanor to The New York Times about her contribution to the national food economy campaign, in which she said: "Making the 10 servants help me do my saving has not only been possible, but highly profitable."

Unlike Daniels, Roosevelt was impatient to see the US get into the First World War. When the nation at last entered the conflict in April 1917, he threw himself into enlarging the navy from 197 ships to the 2,003 in commission at the Armistice. Visiting Europe and its battlefields in the summer of 1918, he became so excited by the prospect of martial glory that he returned to Washington bent upon becoming a naval officer. Yet, once again, he succumbed to illness – this time, double pneumonia. He was still ailing when the war ended.

Thereafter, he found himself plunged into a succession of domestic and political crises. First, Eleanor discovered that he was having an affair with her 26-year-old social secretary, Lucy Mercer. Eleanor had never been enthusiastic about sex. Franklin indulged himself wherever he could, though his attachment to Mercer ran deeper than any other. After the revelation of his infidelity, Eleanor plunged herself into social causes and passionate friendships – perhaps unconsummated – with lesbians. She sustained a façade of marriage to her husband's death, but never again had sex with him.

He resigned his office at the Department of the Navy in August 1920, to take another political leap, standing as vice-presidential candidate in the campaign of James M Cox. The Democratic Party was divided, demoralised and unpopular amid the failure of Woodrow Wilson's presidency. Republican Warren Harding romped to the White House. Roosevelt was deemed to have performed poorly on the campaign trail, appearing to be a lofty, conceited East Coast elitist.

His political career was further damaged by revelations the following year about the so-called Newport Navy Scandal. In 1920, after reports of a homosexual ring at the Newport navy base, an officer appointed to investigate took the extraordinary step of ordering undercover enlisted men to offer their sexual services. If Roosevelt did not authorise this action, he certainly knew of it. When the scandal broke in 1921 and Congress investigated, anger focused less upon the accused than on those who subjected sailors to such experiences in order to expose them. Some of the mud stuck.

All this paled into insignificance, however, beside the blow which struck Roosevelt in August. Suddenly feeling ill, within days he found himself paralysed. Infantile paralysis (polio), a viral condition affecting the spinal cord that baffled medical science at the time, was diagnosed. This intensely energetic, chronically restless man succumbed to deep depression amid the horror of finding himself immobilised. The power of his legs was gone forever. He could stumble a few steps only with heavy steel braces and so he believed that his political career was over.

The years that followed were dominated by a struggle to come to terms with his condition. He founded a medical resort for polio sufferers at Warm Springs, Georgia, and began a business career on Wall Street, specialising in high-risk investments. He made occasional political speeches, the first in 1924. Roosevelt's closer friends saw a gradual change in his personality. He seemed cooler, more patient, but above all resolute. Once at Hyde Park, a visiting clergyman watched him crawl from his desk across the floor to a shelf, then crawl back, clutching a book in his teeth. Asked why he had subjected himself to such an ordeal, Roosevelt answered: "I felt I had to do it to show that I could."

He seemed more serious. His famous charm was succeeded by a more powerful magnetism. In 1928, he delivered the nominating speech for Al Smith's presidential candidature at the Democratic convention, to thunderous acclaim. He deliberately addressed himself to a national radio and newspaper-reading audience, rather than to delegates in the hall. He began to believe that his own political life need not be over. That autumn, he allowed himself to be persuaded to run for the governorship of New York. The Evening Post dismissed his candidature as "pathetic and pitiless". Yet he fought a fiercely determined campaign and won, by a majority of just 25,000 out of 4.2 million votes cast.

Roosevelt was a natural ruler, born to authority and wholly unafraid of its responsibilities. He took office as governor in 1929, the year of the Great Crash, and astonished many people by the populist, anti-capitalist spirit that he swiftly displayed. After 47 years spent assuming that bankers and business bosses knew what they were doing, he came to realise that they didn't. The great American myth of self-reliance, a Darwinian faith in allowing the strong to prevail and the weak to go to the wall, was tested to destruction by the crash. Roosevelt's tenure at Albany was characterised by a commitment to show that, contrary to deep-rooted national belief in personal endeavour, only government could solve the greatest problems that afflicted society. He undertook the regulation of utilities and embarked upon public projects designed to help New Yorkers help themselves through bitterly hard times.

Hoover's Republican Party's failure was terribly apparent. When people talked of Roosevelt as a possible Democratic candidate in 1932, he said dismissively: "I have seen so many presidents at close hand in the White House that I have come more and more to the conclusion that the task is the most trying and most ungrateful of any in America." Yet it was increasingly plain that a Democrat could win in 1932. Roosevelt's conviction that a vigorous government could lift the nation from the slough of despondency found growing support. The senator Henry Ashurst said: "Roosevelt is a man of destiny... He will lead this country out of the Depression and go down in history as one of our greatest Americans."

But plenty of sceptics remained. Some cited his physical infirmity, while others considered him an arrogant, privileged dilettante. The columnist Walter Lippmann wrote that Roosevelt was "without any important qualification for office". He knew nothing of economics and, by March 1932, had yet to devise a plausible platform for his own candidacy. But by the time of the Chicago convention in June, he had recruited a panel of economists to create a programme. He spoke of mobilising money, stopping mortgage foreclosures, making the banking system once more put its faith in "the forgotten man at the bottom of the economic pyramid".

During the convention's fourth ballot, the California delegation suddenly renounced its earlier support for rival John Nance Garner, and declared for Roosevelt. The switch was decisive. Roosevelt became presidential candidate, amid wild enthusiasm.

He was now 50 and a chain-smoker with a huge number of acquaintances, but few people who knew him intimately. For all his irrepressible cheerfulness and bonhomie, scarcely anyone who knew him claimed to know his real thoughts; such was his intense self-control. His family existence was a charade: his children grew up to lead uniformly unsuccessful lives.

After years of cherishing hopes that he might recover use of his legs, now he knew that he could never do more than pose standing for pictures and shuffle a few steps before reverting to his wheelchair. But he possessed a genius for reaching out to millions of people whose circumstances were utterly remote from his own experience. He conveyed a serenity, optimism and strength that touched hearts. It seemed entirely appropriate that a suffering nation should entrust its fortunes to a man who had also known suffering.

The Republicans made the 1932 election campaign easy for him, by adopting a platform based on laissez-faire capitalism. Roosevelt travelled 9,000 miles across the country on his personal train, preaching a gospel of salvation by government action – though he also sought to calm affrighted businessmen by promising to cut government spending. In Baltimore in October, he denounced the Republicans' "Four Horsemen... Destruction, Delay, Deceit and Despair". Walter Lippmann, whose columns wielded much influence, changed his mind and endorsed the Democratic candidate. Felix Frankfurter, a Harvard Law School professor who would become a celebrated Supreme Court Justice, wrote to Lippmann: "If Roosevelt is elected, I think he will often do the right thing, as it were, on inadequate and not wholly sturdy grounds."

On election day, Roosevelt carried the country by 23 million popular votes to 16 million for the Republican candidate, taking 42 states. It was widely said that he won simply because he was not Herbert Hoover, but such sentiments decide many elections. A fortnight before taking office, he gained a stark insight into the hazards of his new job. Landing in Miami after a yachting holiday, he was approached by the mayor of Chicago, Anton Cernak, who had come to seek a political reconciliation.

An Italian bricklayer, Joseph Zangara, fired five pistol shots from a range of 10 yards, intended for Roosevelt. Yet it was Cernak who fell dying. Roosevelt was not only untouched but, to the amazement of his entourage, almost preternaturally calm in the face of an experience that might have terrified him. Zangara went to the electric chair, Roosevelt to the White House.

His first months of office were characterised by a display of presidential activity unmatched in US history. With his overwhelming national mandate and control of both houses of Congress, he thrust through a stream of revolutionary legislation that was rubber-stamped with scarcely a delay or voice of dissent. "The house is burning down," the congressional minority leader told his fellow-Republicans, "and the President of the United States says this is the way to put out the fire."

Roosevelt had declared in his inauguration speech his commitment to lead the nation out of its valley of woe, in such terms that many of his audience wept, and his aide Ray Moley said to the new labour secretary, Frances Perkins: "Well, he's taken the ship of state and turned it right around." This is exactly what Roosevelt did in his first term of office.

At the heart of the "New Deal", the phrase inseparably identified with his presidency, was a commitment to use government as an engine of economic recovery. He created an Emergency Banking Act, which within weeks enabled the struggling bank system to function again. One of his first projects was the Civilian Conservation Corps, which put unemployed men to work in forestry under army supervision for a dollar a day – 239,644 people had enrolled by June 1933.

He cut federal employees' salaries and veterans' payments by $100m. To the fury of the army chief of staff, Douglas MacArthur, he slashed defence spending. He took America off the gold standard, and provided relief to struggling farmers. He created the Tennessee Valley Authority to generate cheap electricity and assist a large poverty-stricken region to regain its feet. He launched a $3.3bn public works programme directed by Harry Hopkins that enlisted the unemployed to build schools, bridges, hospitals – and even commissioned a Hebrew dictionary from workless rabbis. He sought to curb insider share trading by his Securities Act. The administration bore down upon the steel industry, business cartels and Wall Street's fat cats, notably JPMorgan, in a fashion hitherto unknown.

This storm of activity gave Roosevelt extraordinary popularity among the nation's "have-nots". Poor families set his photograph on their living room walls, and revered it as an icon. At the 1934 mid-term elections, the Democrats bucked every historic trend by increasing their support. Yet business leaders were increasingly hostile. They perceived his policies as socialistic, even fascistic. Through his time of office, Roosevelt polarised opinion. Scarcely anyone seemed indifferent to him. He was loved, or hated. Nor were all his policies successful. For all his claims to represent clean politics, he trafficked as much as any predecessor with the city bosses who controlled local party machines. A high-handed attempt to undercut US aviation companies' mail-carrying rates by using US Army Air Corps planes foundered when 12 crashed within a matter of weeks.

He dismayed the Europeans by refusing to join them in pursuing stabilisation measures by pegging currencies. And though Roosevelt was from the outset an opponent of Hitler – he had spent some months in Germany in his boyhood and formed an abiding dislike of German militarism – he showed a weakness for Mussolini, "the admirable Italian gentleman".

Budget director Lewis Douglas resigned in protest when Roosevelt's policies created a deficit of $6bn, an unheard-of sum. The President remained impenitent. To do something, he believed, even if imperfect, was always preferable to doing nothing. He conducted business with a country gentleman's informality. No minutes were taken even of cabinet meetings. Little was decided in writing. Roosevelt talked, decided, invited one or other trusted aide to implement his wishes, and moved on. Far from pursuing unity of purpose among the members of his administration, he kept every department and its chief in its own box. Each was told no more than they needed to know for their own part in the business of government and quite literally worked to death in a startling number of cases. Roosevelt raised to an art form the ability to allow any visitor to leave his office feeling warmed, flattered, assured of satisfaction; only to discover later that the President's intentions were quite different from those that they supposed. More than a few close associates deeply admired Roosevelt the President but deplored Roosevelt the man, evasive and often deceitful. Marguerite LeHand, the secretary who became a mistress and adoring confidante, said later that it was impossible for anyone to get close to Franklin Roosevelt. Yet this is, in some degree, true of all great men. And by 1934, many Americans were convinced that their President was a very great man indeed. He had given them hope.

Roosevelt was re-elected in 1936 by the largest popular majority in US history, almost 28 million votes to 16.7 for Alfred Landon, his Republican rival. Yet his second term was notably less successful than his first. He was frustrated by the resistance of conservatives on the US Supreme Court to his policies. Four judges were ex-corporate lawyers, and struck down his legislation to curb big business as if they themselves were still on company payrolls.

The President moved to get rid of them with unaccustomed clumsiness, introducing a bill enabling them to receive full salaries for life in exchange for resignation. The measure rang every alarm bell in a nation deeply wedded to the separation of powers. Roosevelt was successful in that the court became more tractable to his wishes, and he was later able to appoint liberal nominees to the bench, but he forfeited much goodwill, and exhausted himself, in the protracted battle with Congress and his political opponents. The Supreme Court fight was the worst blunder of his peacetime presidency.

He felt bitter that the great efforts and achievements of his first term were so poorly rewarded. Attacks on him became increasingly personal and virulent. It was claimed that he was syphilitic, that he played the dictator and abused US Navy warships for fishing trips. Fighting back, he displayed astonishing vindictiveness to political and media foes, mobilising against them the tax authorities, FBI and even the Secret Service. His deep-rooted faith in alumni of Groton and Harvard was damaged by a scandal when a former classmate, Richard Whitney, was found to have abused his position as president of the New York Stock Exchange to embezzle its pension fund. He was sometimes embarrassed by Eleanor Roosevelt's increasingly strident social campaigning for liberal causes – and by her indifferent housekeeping at the White House.

The New Deal was still forging ahead, with huge programmes of public works, minimum wage and union rights legislation. But in 1937, when he launched an attempt to balance the budget, the economy tipped into recession, the stock market fell and two million people lost their jobs. The financier Bernard Baruch testified to Congress that the recession was the fault of the New Deal. Roosevelt himself joined speculation that he might not run again in 1940 and that maybe Harry Hopkins could take over his job. He feared that at the next election, a conservative might carry the White House, calling a closure on his great project.

It was the mounting crisis in Europe that revived Roosevelt's flagging energy and enthusiasm for office. America in the late Thirties was deeply isolationist. Cordell Hull was a largely inert presence as Secretary of State. Some senior officials at the Department of State were more hostile to communism than to fascism, and strongly anti-Semitic. The nation instinctively sought to distance itself from fractious, violent, corrupt old Europe. Congress voted in June 1939 to maintain an arms embargo upon all the European powers. A senator, justifying his role in Congress's frustration of Roosevelt's desire for the US to sign up to the International Court of Justice in The Hague, said: "I am a believer in democracy and will have nothing to do with the poisonous European mess."

Roosevelt acknowledged overwhelming public sentiment when he said during his 1936 re-election campaign: "We shun political commitments that might entangle us in foreign wars." That remained his public position three years later, but he was privately convinced that the United States could not quarantine itself from European events. He worked tirelessly to convince opinion-formers that the US must play a part in the crisis.

By a notable irony, Europe's troubles did more to rescue the United States from the Great Depression than all the endeavours of its President. In 1939, the US gross domestic product was still below its 1929 level. The outbreak of the Second World War brought a dramatic surge of foreign investment, as the United Kingdom and France placed huge orders in the US for goods and commodities, then, when Congress relented, for arms. The liquidation of the entire gold and foreign currency reserves of Churchill's nation funded America's surge into wartime economic boom. Only when the British had exhausted their cash reserves did Roosevelt's legendary "Lend-Lease" programme kick in, at the end of 1941, providing the UK by 1945 with loaned arms and supplies worth $27bn.

Roosevelt's desire to assist the UK's survival, and to achieve the destruction of Nazism, was never in doubt. He initiated a private correspondence with Winston Churchill even before his premiership began. Between 1939 and December 1941, however, the President pursued interventionism with notable caution. One of his greatest qualities as America's leader was how he saw himself as the expression of a collective national will. He was by now scarred by many battles with Congress and hostile newspapers, acutely sensitive to the limits of his own power.

He was determined that America's role in the struggle against fascism should not outpace public opinion, in the fashion that had destroyed Woodrow Wilson's presidency back in 1919. As France fell in 1940, Roosevelt claimed to be still doubtful whether to seek a third term. He was feeling the strain of office. "I can't stand it any longer", he said. "I can't go on with it."

In May, isolationist members of his cabinet blocked arms shipments to the allies. Thereafter, however, as Britain stood beleaguered, he began to engage. He sacked the chief isolationists, replacing both the army and navy secretaries with Republicans committed to providing aid. The faithful Harry Hopkins stage-managed a draft for Roosevelt at the July Democratic convention in Chicago. He agreed to run again, loaned 50 old destroyers to Britain in exchange for US leases on British colonial naval bases, and in October pushed through Congress a $40bn appropriation for a dramatic increase in America's armed forces. On 5 November, he was re-elected by 27.2 million votes to 22.3 for the Republicans' Wendell Willkie. Thereafter, his efforts to aid the UK were assisted by the fact that Willkie supported them.

The Lend-Lease Bill passed Congress in March 1941. Roosevelt slowly but steadily increased the US Navy's assistance to the Royal Navy in convoying supplies across the Atlantic, even when American warships began to skirmish with German U-boats. The hawks in his cabinet, notably Henry Stimson and Harold Ickes, pressed him to move further and faster towards war, but he would not be hurried. "I am not willing to fire the first shot," he told Ickes. "I am waiting to be pushed into the situation." When Russia was attacked by the Germans in June 1941, Roosevelt overcame substantial domestic opposition to start shipping aid to the Soviet Union – very slowly between 1941 and 1942, but in vast quantities between 1943 and 1945. In August, he met Churchill at a dramatic naval rendezvous in Placentia Bay off Newfoundland. The British Prime Minister hoped to publicly bring the US into the war as a combatant, but was obliged to come away with only warm expressions of presidential goodwill.

Roosevelt was treading a cautious line, having been re-elected on platform of keeping America out of the conflict. He noted bleakly that renewal of the Selective Service Act, the US military draft, passed Congress on 13 August by just one vote. Many Americans were still desperate to avoid committing to a European war. However, they were much more supportive of tough action against the Japanese, who were already occupying half of China, and now plunging into Indochina. The single act that did most to bring the US into the war was Roosevelt's freeze on Japanese funds in July, and embargo on oil shipments to Japan. Contrary to persistent sensationalist myth, the US had no foreknowledge of the attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December, which Roosevelt memorably dubbed the "Day of Infamy". But it should not have been hard to anticipate, with the aid of decrypted Japanese signals, that war had become inevitable.

The British were deeply resentful of America's tardy entry, driven by circumstances rather than principle. Churchill almost alone embraced his new allies with the warmth that they deserved. Yet Roosevelt's handling of his people between 1939 and 1941 was masterly and brilliantly judged. Had he made a unilateral decision to fight before Pearl Harbor, he would have led to war a deeply divided nation. As it was, Japanese aggression and Hitler's obliging subsequent declaration of war on the US, ensured that the American people were united behind their President through the years that followed.

Roosevelt said exuberantly to a friend back in 1918: "It would be wonderful to be a war President of the United States." Though he was never as unguarded as Churchill in displaying enjoyment of his role from 1942 to 1945, there is little doubt that he found it exhilarating. Many, though not all, of his Congressional difficulties vanished overnight. He could direct the mobilisation of the nation's vast resources with a freedom he had not known since 1933, although unlike Churchill, he never led a coalition government. He was obliged to spend far more time than the British Prime Minister managing his legislature.

He relished his title as national commander-in-chief, but never exercised its functions anything like as comprehensively as did Churchill. Roosevelt's most important decisions were made early in the war. First, he endorsed the need to address the most dangerous enemy first, Germany. Second, he threw his full weight behind shipping supplies to Russia, against the opposition of those who deplored communists, and believed that Stalin would anyway be beaten. Third, in the summer of 1942 he allowed himself to be persuaded by Churchill – against the strong wishes of the US chiefs of staff – that a US army should land in French North Africa and fight a campaign in the Mediterranean. This became Operation Torch, launched in November 1942. In 1943, once again in the face of opposition from General George Marshall, then chief of the army, who wanted an early landing in France, the Anglo-American armies pressed on through Sicily into Italy.

Once it became plain that Russia would continue to hold Hitler's armies, and that eventual allied victory was assured, Roosevelt's chief attention was focused upon forging a new post-war settlement. Always a passionate opponent of imperialism, he dismayed Churchill by making plain his desire to prevent the old European nations from reoccupying their Asian empires. He sought to hasten Indian self-government and independence. Roosevelt was assured that the United States would emerge from the war the strongest and richest power on earth. He sought to use this might to create a new dispensation under a United Nations organisation, its deliberations and decisions dominated by the US, Russia, China and Britain.

Though not quite an Anglophobe, he showed little enthusiasm for British aspirations, nor much concern about her looming bankruptcy. He enjoyed Churchill's company in limited doses, but both men were increasingly prey to jealousy. It has been shrewdly observed that, by 1945, Churchill had grown envious of Roosevelt's power, and Roosevelt of Churchill's genius.

At their two summits with Stalin, at Tehran in November 1943 and Yalta in February 1945, the President brutally disappointed Churchill's hopes of presenting a common Anglo-American front towards the Russians. The President committed to co-operating with or outwitting Stalin, heedless of the Prime Minister's discomfiture. In this, he failed notably. The Soviet leader pursued his own imperial agenda for Eastern Europe with ruthless single-mindedness, exploiting Roosevelt's obvious indifference to, for instance, the fate of Poland.

Roosevelt's relationship with the British Prime Minister was always a friendship of state and never a real intimacy. Although both were patricians, sentimental about the old horse-and-carriage society in which they had grown up, their visions of the future were utterly different. Roosevelt, with his boundless optimism, believed that he could preside at the birth of a better world, while the Prime Minister cared chiefly for victory over Hitler and preservation of the old one. Roosevelt's expectations, for social change in Britain and the fall of Europe's empires, were fulfilled with astonishing speed after 1945. But Churchill's conviction proved justified, that Soviet ambitions were irreconcilable with European freedoms.

Roosevelt's 1944 re-election was never in doubt, but his health was visibly failing. In the last months of his presidency, more and more of his responsibilities were diverted to cabinet members and subordinates. Though a substantial part of the US business community remained implacably hostile to his presidency, most Americans perceived him as the living embodiment of their national purpose, and now also of their march to victory.

Roosevelt was beloved by a generation who perceived him, in considerable part justly, as having saved their society from poverty and despair, bringing government for the first time into a vast range of activities. He had promoted industrial recovery, bank regulation, reflation, workfare, rural electrification, farm support, workplace reform, utility and infrastructure development, environmental conservation and the repeal of the prohibition on alcohol. If the war had done as much as his policies to create the new wealth and power of the United States, he received credit as the leader who had presided over a national triumph.

Like Churchill, he possessed supreme gifts as a communicator, addressing the nation in his legendary radio "fireside chats" with a confiding assurance that no rival could match. He was, at heart, a cold man of the utmost ruthlessness. Yet he presented a façade of warmth and geniality, which his political artistry enabled him to exploit brilliantly. He made friends with his nation in a manner that he never attempted with any individual.

He was never as liberal as either his allies or enemies supposed. A senator was shocked, to hear the President speak carelessly of "the n***** vote". He showed himself largely indifferent to the plight of Jewish refugees struggling to enter the US. But he saw early and importantly the need to extend social justice among his own people, and to curb the hitherto untrammelled power of the industrial and commercial magnates. The New Deal's programmes were most effective socially. They gave hope to an entire generation of impoverished Americans who perceived themselves dispossessed.

Roosevelt died of a cerebral haemorrhage on 12 April 1945, at the Warm Springs, Georgia, home of Lucy Mercer Rutherfurd, his lifelong intimate. His passing shocked his nation, which he had led for longer than any other president. For days, the reporter Studs Terkel found it hard to keep his tears in check. "I can't stop crying," he said. "Everybody is crying." Roosevelt's state funeral became one of the most emotional occasions in Washington's history. He had wielded greater power than the US has ever conceded to a national leader, or is ever likely to again. Most Americans, and much of the world, remain profoundly grateful for the manner in which he exercised it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments