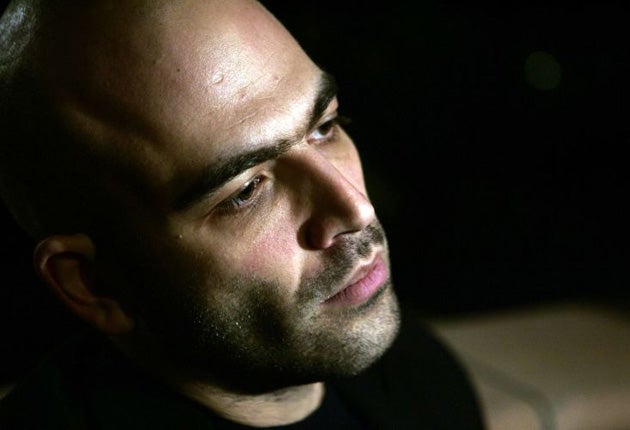

Roberto Saviano: Author of 'Gomorrah' the book exposing the Naples mafia

He dared to expose the truth about the Naples mafia in a book that has been turned into an acclaimed film. Now he is facing death threats

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This was the week Roberto Saviano drank the bitter wine of his success to the dregs. The Neapolitan author is only 28, with a single blazingly vivid and courageous book to his name. This is Gomorrah, the "non-fiction novel" about Neapolitan mafia, the Camorra, which has sold 1.8 million copies in 32 languages, and is now an acclaimed film.

Garlanded with the Grand Jury Prize at Cannes, tipped for a foreign picture Oscar, Gomorrah the film has just opened to rave reviews in Britain. Shot in the degraded Naples hinterland in a gritty, documentary-like style using local people – one of whom, a Camorra gangster on the lam, was arrested this week – the film shows a mafia bereft of glamour and style but brutally masterful in its control of the Naples economy.

But this was also the week when the mob turned on the author: a supergrass reportedly told police that the Camorra planned to kill Saviano "before Christmas". The supergrass later denied the story, but the most feared Camorra killer, Giuseppe Setola, is still on the loose, and was reported to be seeking to buy explosives and a detonator to do the job properly.

The rest of the world was very vague about the Camorra until Saviano came along. Sicily was the home of the real mafia, the ones we cared to know about, whose sadistic brutality could be refined into thrilling romantic nonsense for the big screen. Sure there must be bad people in Naples, too, but the sort of miserable low lifes you find everywhere if you look hard enough.

Saviano, who was born and raised in Casal di Principe, the most mafia-ridden town in the whole Naples area, made the Camorra grimly fascinating. Much of the power of the book comes from the fact that, in the advice given to every starting novelist, he wrote about what he knew.

His father, now dead, was a doctor in this town north of Naples, home to 20,000 people and temporary host to 500 soldiers of Italy's Thunderbolt parachute regiment, dispatched there to assert the power of the state against that of the mob. His mother is a teacher from the north of Italy, whose critical distance from the chaos and infamy of the south taught her son a different way of seeing his surroundings.

"I was 13 when I saw my first body," Saviano says. He was to see many more, and by his tally 3,600 people have been killed by the Camorra during his short life. One of those was still alive, the victim of a shooting, when his father reached him and called an ambulance. For that faux pas he was given a fierce beating. "For a long time he didn't want to show his face in public," Saviano remembers. If a mobster is cut down on the street, you leave him where he is, to give the hitmen the opportunity to finish the job. That was the lesson of the beating.

Growing up in Casal di Principe, stronghold of the Casalesi, the most sanguinary of all the Camorra clans, Saviano learnt the bitter lessons of complicity. A person may live his life here with no connection to the mob, never talking about them, never paying them pizzo or protection, kidding himself they don't even exist. But if someone is shot, no one saw anything, and everyone with any sense vanishes from the scene.

Two weeks ago the uncle of a pentito, or supergrass, whose squealing had led to dozens of Camorra arrests and the confiscation of €100m worth of mob property, was playing cards in a social club in the town centre, under the noses of the paratroopers, when Camorra hitmen burst in and killed him with 18 rounds from an automatic pistol. Everybody fled. Nobody saw a thing.

Saviano and his friends learned the potency of the name of Casal in the area: they would ride their bikes to nearby towns and put local kids to flight merely by mentioning where they came from. "For people in my town," Saviano said recently, "Corleone" – home of the Sicilian Corleonesi clan – "is like Disneyland. I grew up in a cut-throat reality. And I often say that, fortunately or unfortunately, I am made from the same clay as the people I write about. I don't feel any difference in our formation, but in our choices. I didn't choose a different path because I thought that what [the Camorra] do is morally revolting. What I'm trying to do is to understand where their world begins and the legal world ends – and I've understood that they often coincide."

This is the nightmare of southern Italy: you have normal, decent, civilised life and then you have the activities of the gangs, and they seem to be two utterly different realities that have nothing to do with each other. But Saviano learned that in Casal those two worlds are two sides of the same coin. He speaks of a neighbour, a generous, kindly man who invited Saviano to his wedding and who had paid for another neighbour to study abroad. But he was also a gang leader. "It's hard to think that that same clever, generous and kind man could one day kill a guy ... by making him swallow sand, just because he had been flirting with his niece."

These were the realities that any Casal boy with an eye on a prosperous and tranquil future would instinctively put out of his mind. But Saviano was a gifted writer. He grasped that no one before had ever attempted to put these realities on the printed page, and so he set to work. He took part-time jobs that brought him into contact with the low-level punks who deal drugs or keep watch for the gangs. He kept up with his school friends – 40 per cent of young people in the Naples region are unemployed, and for many of those the gang is the only show in town. He burrowed in police and court records, and he produced his book.

And now he is suffering the consequences. He last appeared in public in his home town two years ago this month, when at a meeting in the town piazza he told the town's young people, "Don't let them take away your right to be happy!" The same day, on information received, Italy's interior minister granted him a bodyguard and ordered him into hiding, and he has been living out his Rushdie-esque fate ever since – though, as Salman Rushdie justly remarked this week, "The mafia poses a much more serious problem than the one I had to face. Saviano is in terrible danger, worse than me."

The Camorra may or may not plan to assassinate him "before Christmas", but there is no doubt that Saviano has deeply irritated them. Yesterday Francesco Schiavone, the Casal gang boss who rules the clan from his prison cell, declared through his lawyer that "this great romancer, the spokesman of who knows who, had better shut up".

But Saviano knows that shutting up is no longer an option: he has already said too much, and now his fame and his peril are increasing exponentially and in tandem. And he is tasting the bitter gall of both. Because fame and wealth have come at the expense not merely of personal safety but of everything of value to him: of friendship and love, of belonging, of the raw material to write about.

"I've decided that to give in to the temptation to go back on what I've done would not be a good idea," he told La Repubblica this week. "I feel it would be rather stupid, not merely indecent, to renounce what I've done, to bow before the 'nothing men', people I despise for what they think, how they act, how they live, for what they are in their innermost being." So there will be no repentance, no attempt to unsay what has been said. But his present life, living in a flat in the Carabinieri barracks in Naples when not moved around by his five Carabinieri bodyguards, is intolerable. Saviano has decided to leave Italy, at least for a while.

"Schiavone is in a cell, watched by Carabinieri, and he deserves it for his crimes," Saviano said. "But what is my crime? Why must I live like a recluse, a leper? ... I merely wanted to tell a story, the story of my people, my land, the story of its humiliation ... I don't see any reason for insisting on continuing to live this way, as a prisoner of myself, of my book, of my success. Fuck success, I want a life! I want a house. I want to fall in love, to drink a beer in public. I want to go for a walk, to take the sun, to walk in the rain, to see my mother without fear and without scaring her. I want to have my friends around me and to be able to laugh and not to have to talk about me, always about me, as if I was terminally sick and my friends felt obliged to pay me a dutiful, tiresome visit. I'm only 28!"

A life in brief

Born: 1979, in Naples.

Early life: The son of a doctor, Roberto Saviano grew up in Casal di Principe, a town in the Naples area. He went to school there, before studying philosophy at the University of Naples.

Career: After graduating Saviano became an assistant for a photographer who specialised in mob weddings. This introduced him to mafia life, and he wrote 'Gomorrah', a "non-fiction" novel on the subject, in 2006. The book resulted in death threats from mafia bosses he had exposed, and Saviano had to be relocated from Naples and given 24-hour armed police protection. Since the book's publication he has written for a number of Italian newspapers and magazines about the mafia.

He says: "What I'm trying to do is to understand where the Camorra world begins and the legal world ends – and I've understood that they often coincide."

They say: "The mafia poses a much more serious problem than the one I had to face. Saviano is in terrible danger, worse than me." – Salman Rushdie

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments