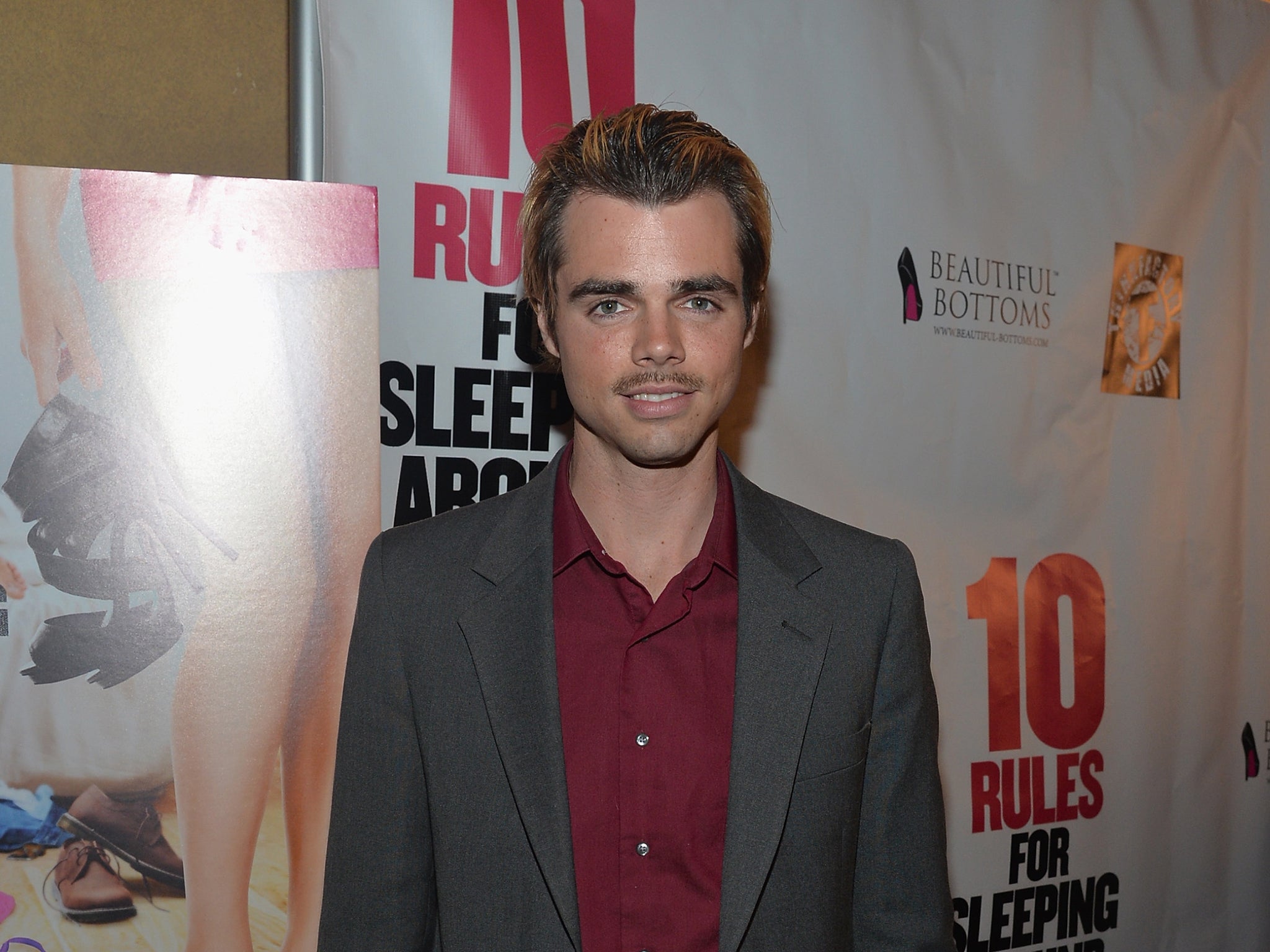

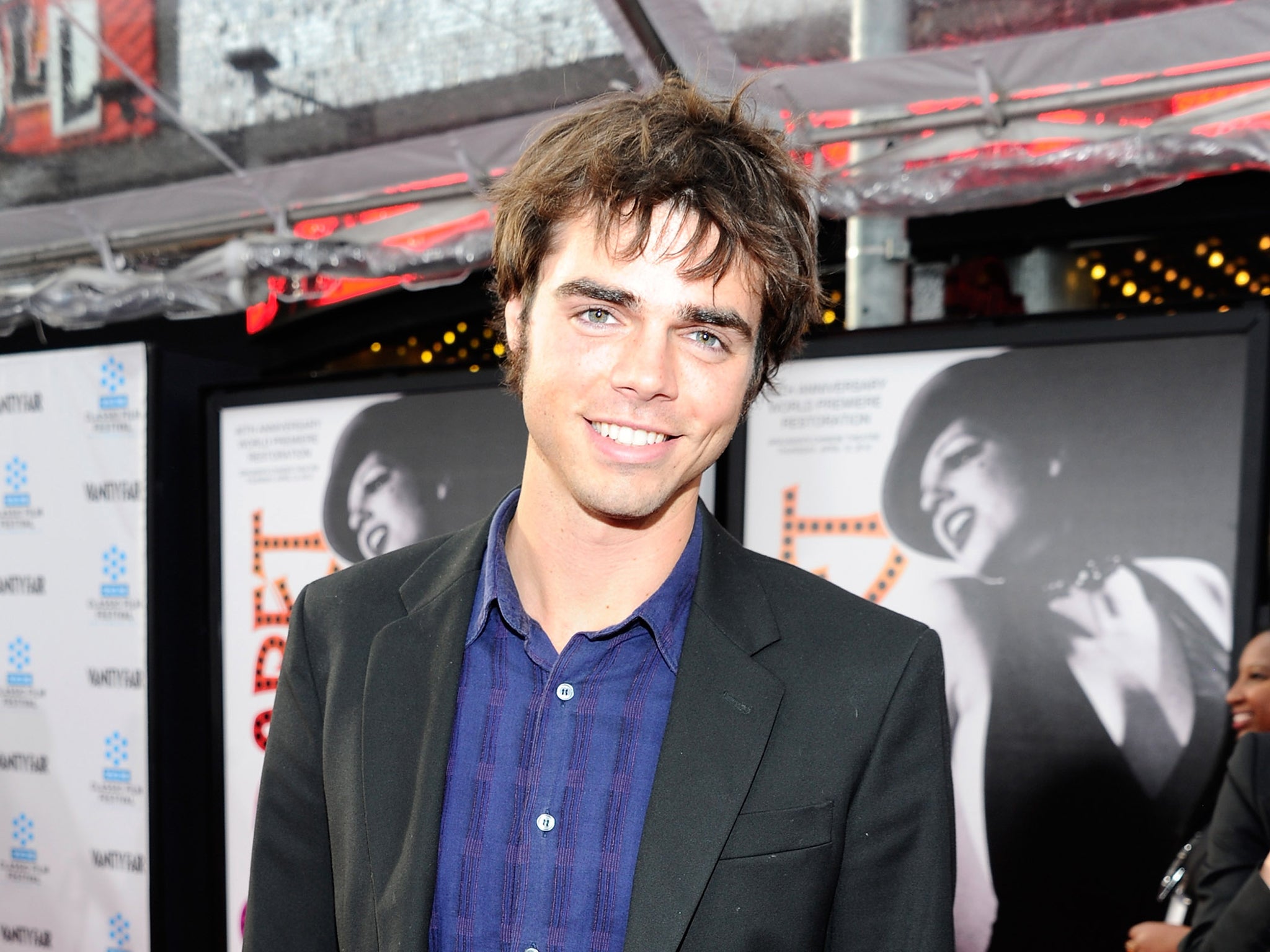

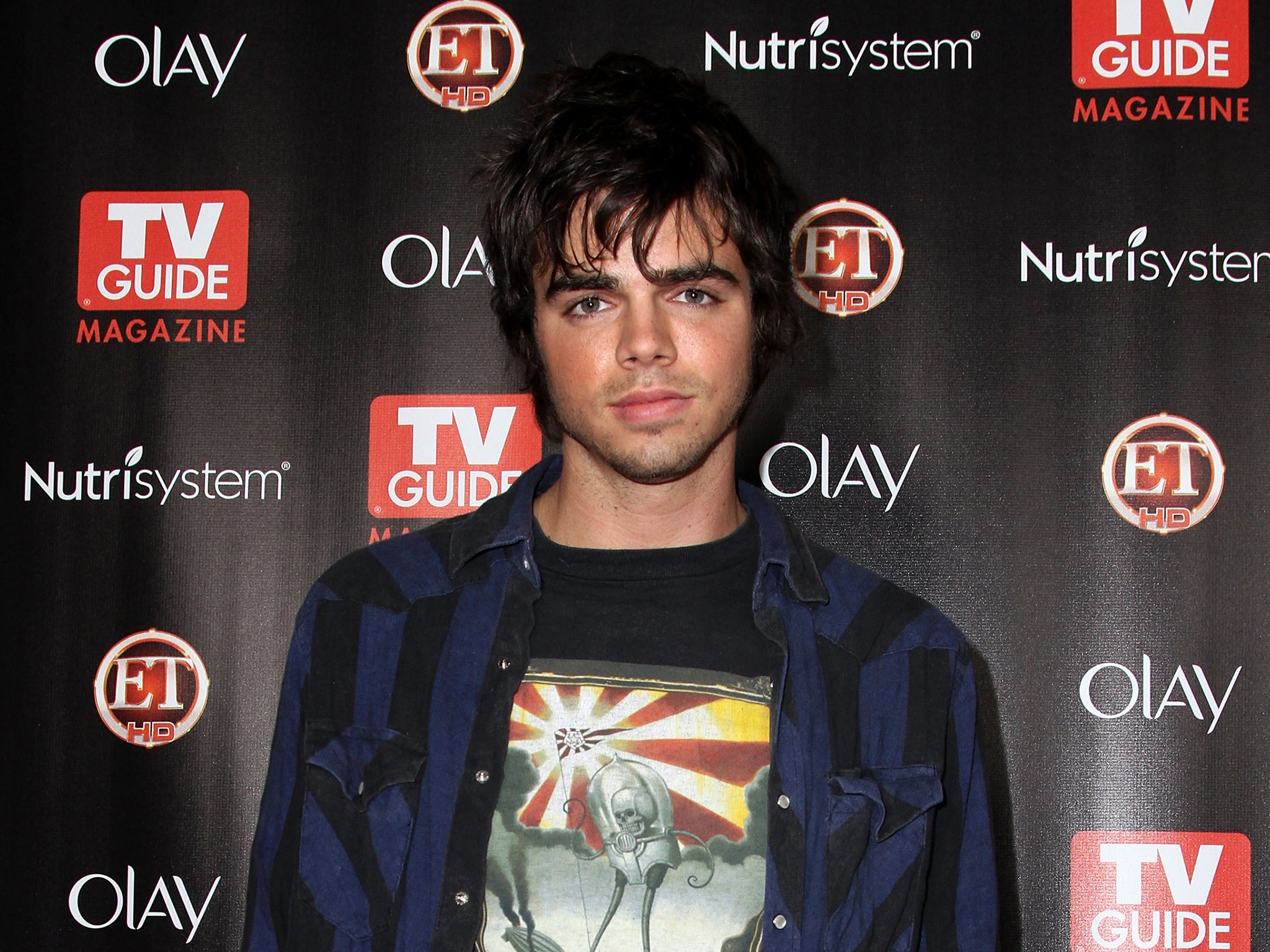

Reid Ewing: The Modern Family actor's cosmetic surgery agony

Ewing suffers from body dysmorphic disorder, and believed surgery would be his lifeline

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Reid Ewing believed cosmetic surgery would be his lifeline.

Then 19 and still new to Los Angeles, the “Modern Family” actor spent much of his time alone in his apartment, taking photos of himself from every possible angle and then analyzing them in torturous detail. Poring over the images, his traced familiar routes across the planes of his face — down the jawline, along the ridges of his profile, across the expanse of his cheeks — always ending at the same conclusion: “No one is allowed to be this ugly.”

So Ewing made an appointment with a cosmetic surgeon, believing the procedure would turn him into Brad Pitt and put a stop to the camera sessions, the loneliness, the irresistible impulse to catalog his flaws.

Instead, Ewing said in a essay for the Huffington Post published Thursday, it launched a cycle of painful procedures that left him even more distressed about his appearance, necessitating further surgery.

Ewing suffers from body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), he wrote, a little-known but relatively common mental illness in which worry about looks becomes an a debilitating obsession. People with BDD may pick at a skin defect only perceptible to them until a real scab appears. They might lose hours in front of a mirror, meticulously working to camouflage their purported flaws, or they might compulsively avoid mirrors at all costs, terrified of what they’ll see. Some develop eating disorders or social anxiety. And studies suggest that more than half of BDD suffers seek out cosmetic surgery, which, as in Ewing’s case, often leaves them as tormented as they were before.

“Before seeking to change your face,” Ewing cautioned in his essay, “you should question whether it is your mind that needs fixing.”

Anxiety over how one looks in the mirror is as old and ubiquitous as reflections themselves. But BDD is something else. It is to grooming what anorexia is to dieting — an anxiety that has become all-consuming, a preoccupation that ruins a life.

Still, the psychiatric condition is surprisingly common: according to the Body Dysmorphia Disorder Foundation, one in 50 people has it. The advocacy group lists several famous names who may have had the disorder, though none were ever diagnosed, including Sylvia Plath, Michael Jackson and Franz Kafka.

“I was afraid of mirrors, because they showed an inescapable ugliness,” Kafka, “The Metamorphosis” author, wrote in his diaries.

Even if Kafka did not suffer from BDD, the story of a man who finds himself turned into a giant cockroach seems an apt metaphor for the illness.

Like most mental illnesses, the causes of BDD are difficult to decipher — usually, a troubling cocktail of genetic predisposition, individual traumas and broader social pressures. According to a report in the journal Nature, people with BBD are more likely to show abnormalities in the visual processing centers of their brain, things that lead them to focus on tiny details rather than examine a bigger picture. In the U.S., men are about as likely to suffer from the disorder as women, the young as likely as the old.

And it’s not a new phenomenon, something that can be blamed on unrealistic modern advertising or 21st century ennui, said Brown University professor Katherine Phillips, one of the leading experts on BDD.

“There are descriptions from over 100 years ago of patients just like those I was seeing in the 1990’s,” she told the New York Times in 2003. “The descriptions were nearly identical.”

One of the earliest comes from turn of the century French psychiatrist Pierre Janet, whose patient was convinced that her face was disfigured by a horrible mustache. The woman refused to leave her house for five years, convinced that her neighbors would yell “Hairy! Hairy!” as soon as they saw her. He poetically termed her ailment “obsession of shame of the body.”

“Dysmorphia phobia” as a psychological diagnosis dates back to 1891, when it was coined by Italian psychiatrist Enrico Morselli. He in turn borrowed the word dysmorphia (literally, “bad body”) from an ancient Greek storyabout a deformed young girl who was hidden from the world by her parents. She was ultimately taken to a shrine and blessed by the goddess Helen, who turned her into a beautiful woman.

In real life there are no goddesses lurking at shrines to free BDD sufferers from their bodies’ shortcomings. But there are cosmetic surgeons, to whom many with BDD ascribe near god-like powers — at least, until their first procedure.

According to a 2010 report in the Annals of Plastic Surgery, people undergoing cosmetic surgery are roughly four times as likely to be BDD sufferers than the general population. But patients are very rarely happy with the outcome — one study put the number whose BDD was alleviated at 9 percent. Another put it at just 2.

“It was a bit like moving the furniture around,” Minnie Wright, 47, told theBBC. “The underlying problem was still there, it just all looked a bit different.”

For Ewing, the failure of his first procedure drove him to total isolation. His doctor seemed “curt and uninterested in [his] worries” and laughed when Ewing woke up in pain, he wrote. Ewing drove from Los Angeles to Joshua Tree, a national park in the desolate California desert, terrified of being seen in Los Angeles bearing the effects of cosmetic surgery. A man he encountered at a gas station “drew back in terror,” when he saw Ewing. A cop took a picture of his swollen face.

In his essay Ewing doesn’t say how much of his memory from that time was colored by his illness — was the man at the gas station really so terrified by his appearance, or was Ewing just convinced that he would be? Regardless, Ewing writes that the cosmetic surgeries he underwent over the course of the following four years were painful and invariably disappointing, both because his doctors seemed unqualified and his face was never really the problem in the first place.

Finally, in 2012, “All the isolation, secrecy, depression, and self-hate became too much to bear,” he wrote. Ewing quit surgery. He sought a psychological solution instead.

With some distance between himself and his surgeries, he is now indignant that his doctors never administered a mental health screening before putting him under their knives. It’s a concern shared by many in the BDD field, including some surgeons.

Lisa Ishii, a plastic surgeon at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, has called on doctors in her field to refuse to operate on BDD patients. She and her team use a questionnaire and clinical interview to distinguish people who simply want to change a particular physical trait from people with BDD.

“They don’t need cosmetic surgery. They need psychiatric care,” she toldNature.

This concern is for the good of surgeons as much as their patients: Asurvey of cosmetic surgeons found that 29 percent were threatened with a lawsuit from an unhappy patient with BDD. Two percent had been physically threatened. In one horrible case, a woman who underwent 12 operations “in the quest for a perfect breast” killed her cosmetic surgeon. Psychiatrists for the defense and the prosecution diagnosed her with BDD (she was ultimately convicted of murder and sentenced to life without parole).

Instead of cosmetic fixes, according to Nature, psychiatrists increasingly recommend cognitive behavioral therapy — a treatment strategy that exposes people to the thing that makes them anxious, then talks them through how to change their response. Depression and anxiety medications can also help treat the disorder.

Ewing, for his part, just wishes he could take his operations back.

“Now I can see that I was fine to begin with,” he wrote. “I didn’t need the surgeries after all.”

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments