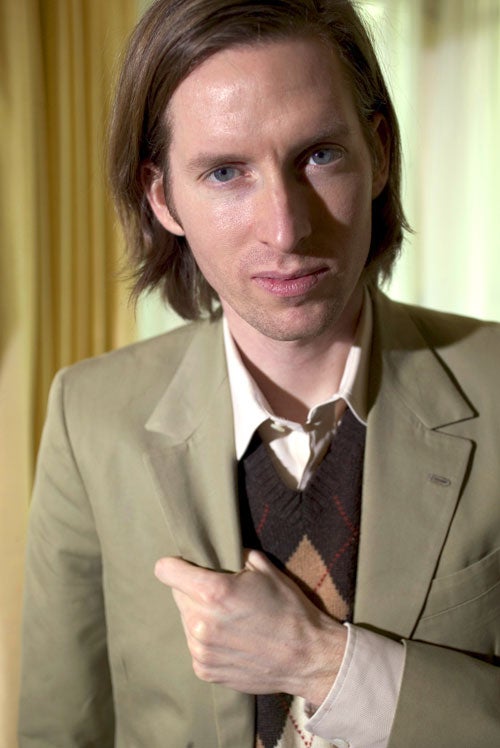

Wes Anderson: The man in the ironic mask

He seems every bit as detached and downright odd as the characters in his films, but this is Anderson playing Anderson. Emily Dugan meets Wes Anderson

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Wes Anderson wants us to think he's weird. He would probably be very happy to find himself staring out of the page under a dictionary definition of "weird". His life and career are all about his own studied brand of peculiarity, and he's not about to change that now.

Which is why, while the IoS interviews him, he is eating. Well, he is doing Wes Anderson's performance of eating. Spinach soup; a separate plate of spinach; a plate of bread and a bowl of baby potatoes are brought at his request. He takes one arch forkful of each, chewing each morsel in slow motion, before pushing his tray aside and announcing he's "quite full".

It is an odd vignette in the series of strange moments that comprise an encounter with one of Hollywood's oddest auteurs. He enters the room, swamped in a furry-hooded green parker, shuffling along with his eyes locked on the floor. "Oh hello, I'm Wes," he says softly, one of America's most celebrated film directors playing the role of a shy schoolboy.

The good manners and bashful demeanour lack sincerity. For a start, he doesn't need to introduce himself: his acclaimed, off-beat films including The Royal Tenenbaums; Rushmore and The Life Aquatic have already brought him two Oscar nominations and a loyal following. Like his cinematic style – credited with inspiring a new generation of indie films such as Juno, Napoleon Dynamite and Garden State – his quirkiness seems a little mannered: this is Anderson playing Anderson.

While for us, the performance began when he came into the room, for him, it began before he even entered the central London hotel where we meet. He tells me he has just missed his lunch because he sat waiting on a hotel reception bench for 45 minutes.

"Apparently the guy who was here before me checked out but left all his possessions," he explains, with a deadpan delivery that is instantly recognisable from his films. "I think it's an unusual situation for a hotel to deal with. I kept thinking, it's just going to be a moment." One can only imagine the sort of explosion a similar situation would elicit from, say, Quentin Tarantino. So, no hissy fit then? "Well, I wasn't wildly excited about it, but I could understand it was sort of an unexpected situation."

Each of his answers is delivered like a line from one of his scripts, with calculated timing and with his face almost expressionless. In fact, his demeanour is of one who's performing for a close-up. Even his posture has artifice, his bony hands motionlessly clasped over a crossed knee and his back bolt upright in an armchair that I am sure he has selected for its symmetry between two lamps.

His clothes look more like items raided from a costume cupboard than something an ordinary person has hanging in their wardrobe. In his bespoke orange-brown corduroy suit, neat yellow tie, pale blue shirt and evergreen sweater, he actually resembles his latest hero, Mr Fox, whose miniature outfit is almost identical. "Oh, I guess you're right," he says, letting out a small, almost girlish giggle of appreciation. There's nothing accidental about the clothes he's chosen. He commissioned the same tailor who made this suit to create a near-replica for Fantastic Mr Fox, which is out on DVD soon and is the reason he has consented to be interviewed. "I thought this would be a good colour for him," he muses.

Clothes play a big part in Anderson films: whether it's the matching adidas tracksuits of the neurotic Chas Tenenbaum and his twin sons, or the trademark red hats and powder-blue jumpsuits of team Zissou in The Life Aquatic, they set the ironic tone of his productions. "In animated movies or live action, the costumes often tell you a lot about the characters, and they're another opportunity to invent something that might be entertaining to the audience or might give something to the movie," he explains. "The costumes interest me as much as the sets, as much as the music; you spend 81 minutes watching a film and these clothes are a big part of what you see in the frame."

It is this all-consuming attention to detail that prompts admirers to describe Anderson as an auteur, but it, and a perceived misanthropic streak, has also brought him trouble. Last October, when it emerged that he had directed most of the London-made animation via email from his desk in Paris, the main criticism was not his distance from the set but his frightening micro-managing.

Despite the huge amount of labour involved in Mr Fox's painstaking stop-motion technique, he would demand (via email) that tiny arm movements be changed, that bread in the background of a supermarket should be kept in a shelf not a refrigerator, or that a pair of shorts should be worn a millimetre higher. "He has made our lives miserable," said Mark Gustafson, director of animation. Director of photography, Tristan Oliver was not much more complimentary: "I think he's a little sociopathic. I think he's a little OCD."

At the mention of this, he is both defensive and dismissive. "It's the sort of thing I don't even really think about, and it's certainly not something I feel I have to justify, because it's just my job. Some movies people make because they are absolutely driven to make it the best thing it could possibly be, then other movies are made for, um, different reasons. This was certainly a movie where everyone was putting their whole heart into it. And even though this is a movie where the frame is filled with details, it's a medium that requires detailed work, because everything has to be manufactured and there are no found objects. Everything has to be made. So someone has got to make those choices and they can either care deeply about them or not, but they're going to be made."

So, while his perfectionism may expose him to the sort of criticism usually saved for more typical Hollywood monster egos, his measured, banally pleasant speech make it a challenge to see signs of a real human being at all. But then we come to discussing his critics. Perhaps because the accusation is that he is too self-consciously quirky, he seems to fumble and drop the façade: he seems genuinely hurt.

"Making any of these movies takes a long, long time and it's sort of my whole life is about making these movies and I work with a group of people that I'm very close to so criticism's not something that I particularly enjoy. It's not my goal to provoke people, I just try to do what I think is good.

"Now the new thing is that your reviews aren't just a series of subjective viewpoints, they're also quantified into a number on a website and you say your reviews add up to this," he sighs. "The fact that one person gives it a 92 and 17, doesn't mean your movie is a 55, it means that you have to decide for yourself. They put a little label on advertisements and say 'certified 83 per cent', that's a bit crazy, because it's not like you're taking an exam when you make a movie."

Later, I check the figure. He hasn't plucked it out of thin air – 83 per cent is his overall rating on the Rotten Tomato film critics' website. Plainly, it has left a scar.

He once said that he could "take a subject that you'd think would be commercial and turn it into something that not a lot of people want to see". When I remind him of this, he denies it is an anti-Hollywood badge of honour. "Oh it's not something I'm proud of," he says, with just a hint too much sincerity. "My first priority is to make the movie that I feel good about, even though my experience isn't generally that you make the movie and then think 'gosh, this is the best'."

Fantastic Mr Fox is a classic example of this bloody-mindedness. While most other directors were turning to CGI and 3D for box-office pay dirt, Anderson chose stop-motion fur puppets for his first foray into animation. His latest project is remaking My Best Friend, a French comedy from 2006 about a misanthropic taxi driver. It is unlikely to trouble James Cameron for the box-office top slot.

But at least he makes films that he's happy with, that he would want to watch, doesn't he? Once again, the façade drops and there is a glimpse of the real Anderson. "No, I don't rewatch them at all," he says. "It's not really a fun experience, because all I see is things that I feel 'OK we did fix that and get that right, but that bit's not as I'd like'. That's no fun at all."

Then the mask is fixed firmly back in place. He thanks me three times, shakes my hand and adds with picket-fence politeness: "It was really so nice to meet you." I don't believe this for a moment but, like his quirky films, the sentiment has just enough charm to be endearing.

Curriculum Vitae

1969 Born in Houston, Texas. Second of three sons of Melver Leonard Anderson, an advertising executive and Texas Ann Burroughs, an archaeologist.

1974-88 Educated at Westchester High School and St John's School, a private school in Houston that inspired his second film, Rushmore.

1988 Begins philosophy BA at the University of Texas in Austin.

1990 Starts writing Bottle Rocket with his college room-mate, the actor Owen Wilson.

1992 13-minute version of Bottle Rocket released.

1994 Moves to Los Angeles.

1996 Bottle Rocket released.

1998 Directs and co-writes Rushmore with Owen Wilson.

1999 Moves to New York.

2001 The Royal Tenenbaums, with Anjelica Huston, is nominated for Best Original Screenplay Oscar.

2004 The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, starring Bill Murray and Owen Wilson is released.

2005 Producer on Noah Baumbach's The Squid and The Whale, which wins two Sundance awards.

2007 Just before The Darjeeling Limited is released, he produces adverts for AT&T, one of which sparks controversy for what is called an "ignorant" portrayal of the Lebanese political situation.

2009 Fantastic Mr Fox released in cinemas amid criticism of Anderson's obsessive direction style via email from his Paris apartment.

Fantastic Mr Fox is out on DVD and Blu-Ray on 1 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments