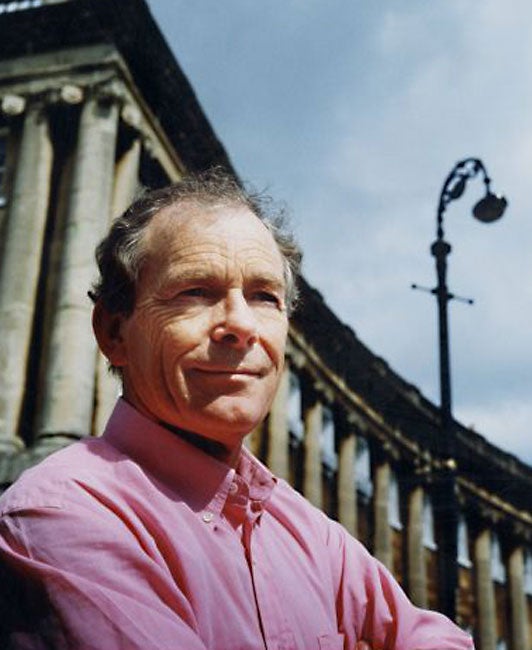

Sir Simon Jenkins: History man

After more than 40 years in journalism, he will become the public face of the National Trust

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sir Simon Jenkins is so grand that he really should be bought and preserved by the National Trust, so that successive generations can admire the wondrous architecture and exquisite furniture of his mind. Instead, the trust has chosen him to be its next chairman.

After more than 40 years in journalism, Sir Simon will now become the public face of an organisation with a membership several times the combined size of the Conservative and Labour parties – a £300m a year charity that ranks with the Ministry of Defence and the Church of England as one of the country's three biggest landowners. Seven hundred miles of coastland, 615,000 acres of countryside, and 10,000 buildings housing 5,000 tenants, including 300 palaces, 4,300 employees and more than 52,000 volunteers will have Sir Simon to speak for them.

It might seem a strange appointment. The words "National Trust" convey an image of huge old houses set in parkland somewhere miles from town, inhabited by families who trace their lineage back to the Plantagenets, whereas Jenkins is a Londoner through and through, a Sixties liberal turned conservationist, for whom the countryside is somewhere to visit for pleasure and self-enlightenment.

For all his urban sophistication, Jenkins loves good architecture and anything that is old and beautiful, particularly if it is an old building with a history. People who have spent their lives in the study and preservation of old buildings are said to resent him because he does what they do, but makes much more money out of it. If so, they will have all the more reason after this week's announcement.

But within the National Trust there is a certain relief that, from 1 November, he will be metaphorically inside the tent. "Mr Jenkins has long been a public friend and occasional critic of the National Trust, and claims to have visited every one of the trust's houses in England and Wales," said the official announcement of his appointment.

He has certainly been an "occasional" critic. The National Trust and its younger twin, English Heritage, he once wrote, "are reaching old age – arthritic and bureaucratised. Their staff occupy quantities of space with private offices and flats, space that could be let profitably to others if not used for display. Both of these organisations could usefully let lesser properties to custodians on long leases and free them from bureaucracy. As for the Trust's guidebooks, they are academically splendid, but for the casual visitor hopelessly difficult...".

He has not forgiven the trust for its £4m "publicity stunt", launched 10 years ago, to "save" Snowdon, Wales's favourite mountain. A hill farmer was selling his sheep farm, because his legs could no longer cope with the daily climb to where his flock grazed. The trust spotted an opening to raise money and generate publicity, and persuaded a lot of people to part with money to prevent a private sale when, according to Jenkins, Snowdon was never under threat, because of its status as a national park, whereas the less known but equally beautiful Cambrian mountains had no such protection. The hilltops are now decorated with rows of wind turbines. Jenkins thinks the trust should have directed its money to protecting its skyline.

"The National Trust is run from London like a nationwide dukedom," Jenkins wrote, on another occasion. "Its factors, the land agents, dominate its command structure. Round them hover a privileged chaplaincy of aesthetes who worship the buildings in their charge. Other ranks are certainly of less account: the Trust's multitudinous advisers, wardens, members, even titled tenants seem slightly below the salt." This, believe it or not, was part of an essay defending the National Trust, as the approach of its centenary in 1995, against an American journalist who had attacked it as an anachronistic reflection of Britain's former class system. Yes, the trust is ridden by class, Sir Simon concurred. That is its charm.

"Only inverted snobs need apologise," he wrote. "The pleasure of the past is always the pleasure of illusion. But the illusion conveyed by most Trust properties is more vivid and true to their past than other forms of public ownership... To accuse the Trust of being effete, a little bumbling and slow to embrace change is really to accuse it of being what its public likes it for being."

Jenkins himself is certainly not an inverted snob. He loves a smart party. When the former chairman of English Heritage, Sir Jocelyn Stevens, threw a £300,000 bash for 380 guests at Eltham Palace, Jenkins praised him for making excellent use of an interesting old building. The parties thrown by Sir Simon and Lady Jenkins are a highlight of the London social scene, at which the location is as important as the elite guest list. One of the first that people remember was in the Battersea power station in the 1980s, after it had been decommissioned by the Central Electricity Board. As well as treating their friends to champagne and canapés, they helped to promote the case for conserving the building, which still stands.

"Parties such as the Jenkinses' burst upon our recession-darkened firmament with the brilliance of a firework," Clive Aslet, the editor of Country Life, wrote after being invited to another of these events, in an 18th-century palace in St James's Square, London. "Like the corporate parties which try to imitate them, the Jenkinses have a concealed seriousness of purpose."

Born in 1943, the son of a doctor, Jenkins joined The Times a few months after graduating from Oxford University. He was editor of the London Evening Standard from 1976 to 1978, but lost out when the paper was merged with its rival, the Evening News, and went off to be political editor of The Economist. He edited The Times from 1990 to 1992, but was axed after failing to increase sales to the level his proprietor, Rupert Murdoch, required. Neither of his stints as an editor matched his success as a writer. For more than 15 years, he has been a regular columnist, principally for The Guardian and The Sunday Times.

He was knighted in 2004, but does not regularly use the title. His wife, better known as Gayle Hunnicutt, is a Texas-born actress who played Vanessa Beaumont in the TV soap Dallas. They have one son, and a stepson by her first husband, the actor David Hemmings.

In some respects, Jenkins has swum with the stream of intellectual fashion. In the 1990s, as a member of the Millennium Commission, he was an enthusiast for the Greenwich Dome, pleading with the Government not to abandon it. Later, he was a scathing critic of the Iraq war and the Government's record on civil rights. But at other times, he has been prepared to be deliberately unfashionable. Although he says he could never understand how anyone could find pleasure in seeing an animal being torn to pieces, he fought a rearguard battle against the abolition of hunting with dogs, because of its place in rural culture.

He loves churches. Anyone who doubts that need only glimpse at the massive tome he published in 2000, entitled England's Thousand Best Churches, full of notes on the treasures and architecture of 1,000 churches, organised by county, with maps and star ratings. This is not, however, matched by any such reverence for the church – which he once described as "like the Conservative Party and the BBC – overcentralised, overwrought and losing market share" – its bishops or its commissioners. Indeed, he once suggested that the one useful thing that the Archbishop of Canterbury could do with the church's vast assets is spend the whole lot on its architectural infrastructure. "If Dr Williams cannot revive the Church of England, he can at least revive the churches of England," he suggested.

It could also be true that he has been to all 300 big houses and palaces run by the National Trust. He has certainly visited a lot of stately homes, particularly when researching his 2003 tome England's Thousand Best Houses – the follow-up to the highly successful church guide. He wants them preserved and opened to the public, but not for anything so vulgar as education.

"I love museums in their place, but museumitis and its politically correct henchman 'education' are now a raging disease in English country houses," he once complained. "Filling old rooms with signs, captions, notices and waxworks does not amount to a 'lifestyle message'. This tendency is no longer confined to local council houses, but is seeping, like dry rot, through the rooms of National Trust and English Heritage, infecting them with video rooms, staff quarters and health and safety signs."

No, what an old stately house needs is not gimmicks to pull in the tourists, but an old stately family living within its walls. A few years ago, he put up a remarkable defence of the eighth Marquess of Bristol, who was furious when the National Trust would not allow him to move into his ancestral home in Suffolk. The trust had accepted the house to spare the family from death duties, but had allowed them to continue living in it until the drug-addicted seventh Marquess sold them the lease to pay his debts. Not many Sixties liberals would have taken up the Marquess's cause, but Jenkins did, on the grounds that "a house lived in by the family which built it, or at least whose story can be traced in its walls, furniture and pictures, is worth a dozen sterile museums. The sight of a child's pushchair on the lawn is worth £5 on the ticket price".

The trouble with the National Trust, he complained, is that it was that it had become thoroughly "Blairised". He added: "Its highly centralised bureaucracy runs what amounts to a nationalised stately home industry. The trust's leadership is currently taking a leaf from Downing Street's book by trying to fix elections to its ruling council. It probably refers to the Marquess of Bristol as Mr Fred Hervey."

So, an encouraging message to the old aristocrats of England: the National Trust's new chairman knows how to address you correctly, and he wants you to be at home.

Born 10 June 1943.

Education Mill Hill School, London, and St John's College, Oxford.

early life Began career in journalism at Country Life magazine. Moved to the Times Education Supplement, before editing The Sunday Times's investigative Insight page.

Career Became editor of London's Evening Standard while still in his early 30s. Moved to The Economist as political editor in 1979, holding the post until 1986. Edited The Times from 1990 to 1992. Has also taken up numerous posts outside journalism, including a place on the board of British Rail for 11 years. Deputy chairman of English Heritage between 1985 and 1990. Named Journalist of the Year in 1988 and Columnist of the Year in 1993. Currently writes for The Guardian and The Sunday Times.

He says "I have attended many Stonehenge consultations. They are raving madhouses."

They Say "Simon is a hugely respected public figure with a deep understanding of what we do." Fiona Reynolds, outgoing director-general of the National Trust

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments