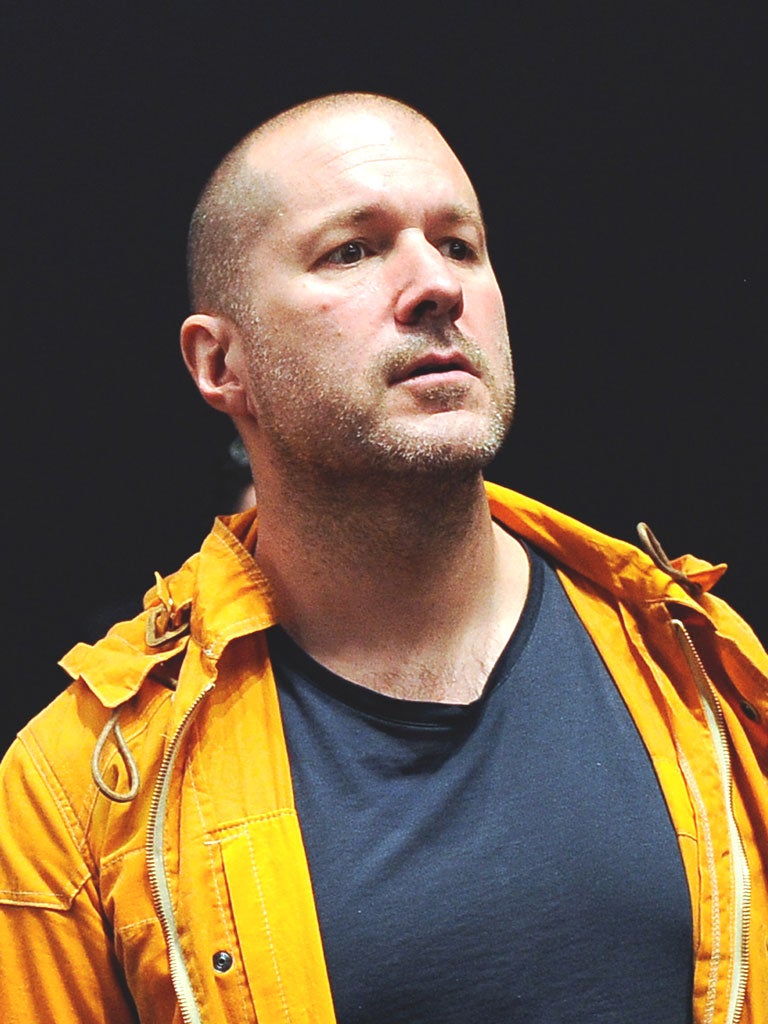

Sir Jonathan Ive: Knighted for services to ideas and innovation

Sir Jonathan Ive, Apple designer, has been the driving force behind some of the best-loved gadgets of our age. Mark Prigg asked him about his methods and motives

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sir Jonathan Ive, "Jony" to his friends, is arguably one of the world's most influential designers. The 45-year-old was born in Chingford, London, and went to the same school as David Beckham. He met his wife, Heather Pegg, while in secondary school. They married in 1987, have twin sons and now live in San Francisco.

As Apple's senior vice-president of industrial design, he is the driving force behind the firm's products, from the Mac computer to the iPod, iPhone and, most recently, the iPad.

He spoke to The Independent at the firm's Cupertino headquarters.

Q: You were recently knighted for services to design – was that a proud moment?

A: I was thrilled, and at the same time completely humbled. I am aware I'm the product of growing up in England, and the tradition of designing and making, of England industrialising first. The emphasis and value on ideas and original thinking is an innate part of British culture, and in many ways, that describes the traditions of design.

Q: Why did you decide to move to California?

A: There is a remarkable optimism, and an attitude to explore ideas without fear of failure. There is a simple and practical sense that a couple of people have an idea and decide to form a company to do it. I like that practical, straightforward approach. There's not a sense of looking to generate money, its about having an idea and doing it – I think that characterises this area.

Q: What makes design different at Apple?

A: We struggle with the right words to describe the design process at Apple, but it is very much about designing and prototyping and making. When you separate those, I think the final result suffers. If something is going to be better, it is new, and if it's new, you are confronting problems and challenges you don't have references for. To solve and address those requires a remarkable focus. There's a sense of being inquisitive and optimistic, and you don't see those in combination very often.

Q: How does a new product come about at Apple?

A: What I love about the creative process, and this may sound naive, but it is this idea that one day there is no idea, and no solution, but the next day there is an idea. I find that incredibly exciting and conceptually actually remarkable. The nature of having ideas and creativity is incredibly inspiring. There is an idea which is solitary, fragile and tentative and doesn't have form. What we've found here is that it then becomes a conversation, although remains very fragile. When you see the most dramatic shift is when you transition from an abstract idea to a slightly more material conversation. But when you make a 3D model, however crude, you bring form to a nebulous idea, the process shifts. It galvanises and brings focus from a broad group of people.

Q: What makes a great designer?

A: It is so important to be light on your feet, inquisitive and interested in being wrong. You have that wonderful fascination with the what-if questions, but you also need absolute focus and a keen insight into the context and what is important – that is really terribly important. It's about contradictions you have to navigate.

Q: What are your goals when setting out to build a new product?

A: To design and make better products. If we can't make something that is better, we won't do it.

Q: Why have Apple's rivals struggled to do that?

A: Most of our competitors are interested in doing something different, or want to appear new – I think those are completely the wrong goals. A product has to be genuinely better. This requires discipline, and that's what drives us – a genuine appetite to do something that is better. Committees just don't work, and it's not about price, schedule or a bizarre marketing goal to appear different – they are corporate goals with scant regard for people who use the product.

Q: When did you first become aware of the importance of designers?

A: The first time I was aware of this sense of the group of people who made something was when I first used a Mac – I'd gone through college in the Eighties using a computer and had a horrid experience. Then I discovered the Mac, it was such a dramatic moment and I remember it so clearly – there was a real sense of the people who made it.

Q: When you are coming up with product ideas such as the iPod, do you try to solve a problem?

A: There are different approaches – sometimes things can irritate you so you become aware of a problem, which is a very pragmatic approach and the least challenging. What is more difficult is when you are intrigued by an opportunity. That, I think, really exercises the skills of a designer. It's not a problem you're aware of, nobody has articulated a need. But you start asking questions, what if we do this, combine it with that, would that be useful? This creates opportunities that could replace entire categories of device. That's the real challenge, and that's what is exciting.

Q: Has that led to new products within Apple?

A: Examples are products like the iPhone, iPod and iPad. That fanatical attention to detail and coming across a problem and being determined to solve it is critically important – that defines your minute-by-minute, day-by-day experience.

Q: Your team of designers is very small. Is that the key to its success?

A: The complexity of these products really makes it critical to work collaboratively, with different areas of expertise. I work with silicon designers, electronic and mechanical engineers, and I think you would struggle to determine who does what when we get together. We're located together, we share the same goal, have the same preoccupation with making great products. We've been doing this together for many years – there is a collective confidence when facing a seemingly insurmountable challenge, and there were multiple times on the iPhone or iPad where we had to think, will this work? We simply didn't have points of reference.

Q: Is it easy to get sidetracked by tiny details on a project?

A: When you're trying to solve a problem on a new product type, you become completely focused on problems that seem a number of steps removed from the main product. That problem solving can appear a little abstract, and it is easy to lose sight of the product. I think that is where having years of experience gives you that confidence that if you keep pushing, you'll get there.

Q: Can this obsession with detail get out of control?

A: It's incredibly time consuming, you can spent months on a tiny detail – but unless you solve that tiny problem, you can't solve this other, fundamental product. You often feel there is no sense these can be solved, but you have faith. This is why these innovations are so hard – there are no points of reference.

Q: How do you know you've succeeded?

A: It's a very strange thing for a designer to say, but one of the things that really irritates me in products is when I'm aware of designers wagging their tails in my face. Our goal is simple objects that you can't imagine any other way. Simplicity is not the absence of clutter. Get it right, and you become closer and more focused on the object. For instance, the iPhoto app we created for the new iPad, it completely consumes you and you forget you are using an iPad.

Q: What are the biggest challenges in constantly innovating?

A: I am still surprised how difficult it is, but you know exactly when you're there – it can be the smallest shift, and suddenly transforms the object, without any contrivance. Some of the problem solving in the iPad is quite remarkable, there is this danger you want to communicate this to people. I think that is a fantastic irony, how oblivious people are to the acrobatics we've performed to solve a problem – but that's our job, and I think people know there is tremendous care behind the finished product.

Q: Do consumers really care about good design?

A: One of the things we've really learnt over the last 20 years is that while people would often struggle to articulate why they like something, as consumers we are incredibly discerning, we sense where there has been great care in the design, and when there is cynicism and greed.

Q: Users have become incredibly attached, almost obsessively so, to Apple's products – why is this?

A: It sounds so obvious, but I remember being shocked to use a Mac, and somehow have this sense I was having a keen awareness of the people and values of those who made it. I think that people's emotional connection to our products is that they sense our care, and the amount of work that has gone into creating it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments