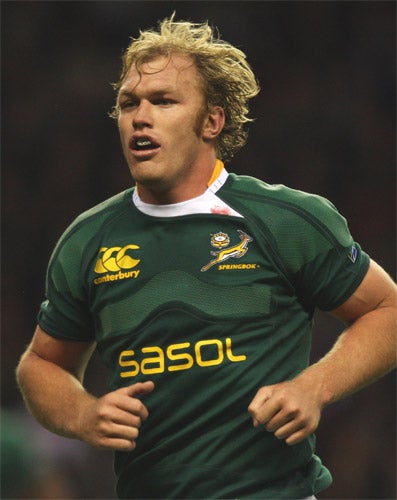

Schalk Burger: 'I have never seen myself as a dirty player'

Two sides of The Incredible Schalk: capable of violent gouging of a British Lion but gentle giant off the field. Richard Wilson speaks to Schalk Burger

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is in the great tensions of confrontation, those small battles to overcome your own limits, that Schalk Burger has found so much of his meaning. That has always been his way, since he infuriated his cricket coaches as a teenager by injuring himself in a local rugby match and then decided to change to the oval-ball game. He has accumulated a few dark smirches along the way, when his blood has risen so ferociously that it dispelled the last of his restraint, but then perhaps we might at least allow that the edge of things is a difficult place to keep your footing.

There is a profound separation in his life, the certain distinction between that looming, grimacing presence on the rugby field – when it seems as though that 6ft 4in frame is the very essence of all our distilled rage – and the insouciant, almost languid figure off the pitch. Burger, of course, is not the first performer to be so utterly transformed in taking to the field, and sport is nothing if not a means to reimagine so much of yourself.

But then how do we reconcile the man who is so generously polite, whose voice is so soft and gentle that it lilts so soothingly, with the flanker who showed such callous disregard for the ethics of his sport when he appeared to gouge Luke Fitzgerald's eye in the second Lions Test in Pretoria last June? Maybe we can only accept that Burger, too, still strives to resolve these two aspects of his character.

He has never spoken about the Fitzgerald incident, for which he received a yellow card at the time then a subsequent eight-week ban, and a reluctance emerges when we ask about it directly. It is enough, he tries to say, that it happened, that it was dealt with, and that he wishes to put it behind him. He has only spoken to Fitzgerald once, at the hearing that followed the Second Test, and his voice trails off after revealing this, as if doubtful about what more might be said.

"I've been looking forward to putting that all behind me," he says. "The first two or three weeks [of the ban] weren't great, but after that I played a bit of golf and had long weekends for the first time in two-and-a-half years. So despite the massive negative, I had some positives as well. We saw each other briefly [the next day], but not too much was spoken between us. I think enough's been said, I don't think there's much to add to it."

But his was already an uncompromising reputation, hardened round the edges by previous indiscipline and given such depth by feats of endurance that suggested a gruff fearlessness. He once played on against Scotland after suffering a spine compression that caused his left arm to go numb and later kept him out for six months after an operation to repair the damage. The South Africa coach at the time, Jake White, remarked that "it's like losing three players".

Yet this might, this ferocity, that is so much of Burger's name that he is known back home as The Incredible Schalk (his first name is pronounced in the same way as Hulk), seems darker when set against the violence that seems such an inevitable, and saddening, part of rugby's close-quarters combat. Burger, now, might never escape the shadow of that confrontation with Fitzgerald.

"I've played rugby a certain way for as long as I can remember, so that's my style," he says. "Off the field I'm pretty relaxed, I don't get too worked up. And I've never seen myself as a dirty player, just someone who wants to enjoy it and play 100 per cent. I've just got to be aware that I've maybe got a bit of history now and people are going to be looking out for it. You've got to remind yourself every now and then to calm down and take it easy."

Through suspension and injury – including two ribs damaged during the Tri-Nations – Burger has played little rugby during the past six months. Life on his parents' farm in Port Elizabeth, where his family runs a wine business, has its own compensations. But then the forward named world rugby's player of the year in 2004 can only accept the relaxation – and its reviving effect on a body pushed beyond reasonable demand during the past two- and-a-half years – for so long.

He is 26 and the game still represents the central emphasis of his life. We have heard the talk, too, that he is on the verge of joining Saracens, either on a long-term contract or as part of a tie-up with his current employers, Western Province. He admits to a desire to one day play abroad, to take advantage of those horizons that rugby spreads out for those at the forefront of the game, but not in the immediate term.

"It's always an option, but I'm contracted to Western Province until 2011," he says. "I've always wanted to come overseas and spend one or two seasons here, so it's something I want to do. I think the next phase of my life might be coming over here and playing a bit of rugby. But I want to stick in South Africa until 2011, play the World Cup, then I'll start moving after that."

It has been a difficult series of autumn internationals for South Africa, beating Italy but losing to France and Ireland. Burger, who scored the only try of the game in Dublin, insists much of this is sluggishness in a side who currently hold the World Cup and the Tri-Nations. The international calendar can come to feel like a grind, particularly now that professionalism has separated the players from the social side of a sport that for so long considered the interaction away from the field as just as integral to the playing of the game.

During the Lions series, the visitors declined invites to share beers after matches, a practice that has become routine in the Super 14. For Burger, joining up with the Barbarians for The MasterCard Trophy match against New Zealand at Twickenham next Saturday provides an opportunity to return to some of rugby's older traditions.

"The biggest thing in the profes- sional era is probably the lack of characters to come into the game," he says. "Maybe you don't get as many opportunities to truly express yourself off the field. With the Barbarians, you meet the guys on a different level. When you meet them in the bar, just having a beer and being themselves, that's when to really make some friends."

He might regret the lack of characters, but a player whose father was a lock for South Africa and who built a cricket pitch on the farm for his sons, and who has himself become a figure of fierce contradictions, is not lacking in identity. In confrontation, we see the best and the worst of Burger.

Schalk Burger was talking ahead of the Barbarians v New Zealand match at Twickenham next Saturday

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments