Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.'My first memory of Cook," mulls Richard Ingrams, "is him walking into The George pub in Seven Dials in the early Sixties, dressed in a beautiful suit, and telling my wife Mary, 'I have reason to believe there is a very rare bee lodged in your knickers and I wonder if I could investigate further'. Later he helped Mary – who adored him – with her own alcoholism and manic depression, although Peter had issues with AA's [Alcoholics Anonymous] higher power aspect. He'd refer to 'God's blessed gift of cancer'. Which was perfectly fair, I think."

Ingrams had co-founded Private Eye and Cook – who died 20 years ago this Friday – became its proprietor, its real-life 'Lord Gnome'. Ingrams admires him for publishing dangerous things, such as the names of the gangsters Reg and Ronnie Kray (while Ingrams was on holiday) but it's Cook's words of whimsy which most echo. "They still run through my head and cheer me. Like when Dudley [Moore] sang, 'How Beautiful Are The Feet' in falsetto, the exquisite way Peter added, 'Ooo, what lovely feet, I don't think I've ever seen such beautiful feet'. And after Dudley – portraying Spiggy Topes of The Turds – said of a London hotel, 'We went in there perfectly normally dressed, wearing gold lamé knickers and feathers up our bottoms', Peter replied, 'Yet still they turned you away'. That's such a brilliant remark."

During his random visits to the Eye (where his ceremonial chair remains, kept empty), Cook would phone up various authorities, such as the Ministry of Technology, to object to "all these bloody machines everywhere". "I once heard him phoning the Foreign Office to discuss how Russians were listening to him through his drainpipes," says Ingrams. "Such mad fantasy is sadly lacking today."

It was long – but unsuccessfully – Cook's desire to write a regular strip in Private Eye entitled 'The Holy Bee of Ephesus'. Elizabeth, Cook's youngest sister, born when he was 14, explains, "Peter imagined a bee that had buzzed around the Cross – was witness to the crucifixion – and became holy.

It's a family tale that Peter once smuggled a terrapin home from Gibraltar – where our father, after being a colonial Political Officer in Nigeria, became Financial Secretary. Peter wept uncontrollably when his terrapin poked its head out of a teapot and was confiscated by customs."

When Peter was three months old, both his mother and father mainly lived abroad, so – report his biographies – Peter was raised by his nanny, granny, aunt or boarding school staff. Yet previously unreported has been the influence of his aunt's husband. "Uncle Roy," explains Elizabeth, "used to tie cotton very gently around the waists of bees. Roy was fond of pond life; was an eccentric, wine connoisseur and old-fashioned Tory anarchist who believed in nature's law and had wonderful ideas, but also ruthless ones – almost eugenicist". (Peter, when at Radley public school, wrote an essay calling for castration of the working classes. "Although not surgical castration, just chemical," he later cringed.)

"As a child I used to go into Peter's bedroom, to try and piece him together," says Elizabeth. "The things I most enjoyed were his beautiful sea-shells packed in cotton wool in aromatic soap boxes and his large collection of ties – especially a wonderful pale blue satin tie with musical notes on. Whenever he phoned me up he'd always begin 'Herrein Doktor Cook?' – formal old-school German. He'd often talk in a Cold Comfort Farm way about the implacable skies and used enormous grandiose adjectives. He enjoyed the deep pleasure of words and getting them slightly off-key. Usually straight-faced on stage, he actually laughed a lot, but I mostly remember the beginning of his chortle. His cheeks would puff in and out, like they had blow-holes, and I'd know something very funny was on the way out."

Cook's parents, after (post-colonial) retirement, kept a visitors' book in their hall and one inscription reads, 'Curtains down, curtains up, son exhausted' – a reference to Peter's bi-annual job of changing his mother's summer and winter curtains. "The stateliness of the curtain hangings was hilarious, the whole rigmarole," says Elizabeth (who still has the faded pink winter curtains). "Peter enjoyed getting stuck in, loved having a project. One Christmas I couldn't eat turkey, so in the sort of sudden rush Peter relished, he set off to find an alternative and ended up in a nursing home – where our father had been with Parkinson's disease – and raided their kitchen for fish."

Elizabeth notes that their parents – often characterised as blimpish – were "frightfully proud" of Peter's success and humour, except for his dig at war sacrifice in Beyond the Fringe.

Was there humour between Peter and his father, after the latter's Parkinson's took grip? "You know how in Waiting for Godot, Estragon says, 'That wasn't such a bad little canter'?" reflects Elizabeth, "Well, yes, there were good little canters." Members of the family believe that Alexander Cook's vulnerability allowed Peter to finally get closer and that the way he portrayed the infirm Lord Stockton/Macmillan in a mechanical wheelchair in 1986 was "uncannily" like his father. "Peter had our father's Nigerian diaries typed up, with spiral binding and a little cover window," says Elizabeth. "Then he investigated the mystery of the death in Kuala Lumpur of our colonial officer grandfather Edward, and discovered it was suicide."

Rather than just being, as some claim, 'the world's greatest slacker' in the 1980s, those are things which occupied Cook's mind. Sister Elizabeth feels "Peter was terribly sensitive to changes in the moods and responses around him in a way that was intolerable to him, so often drank to excess to blunt this".

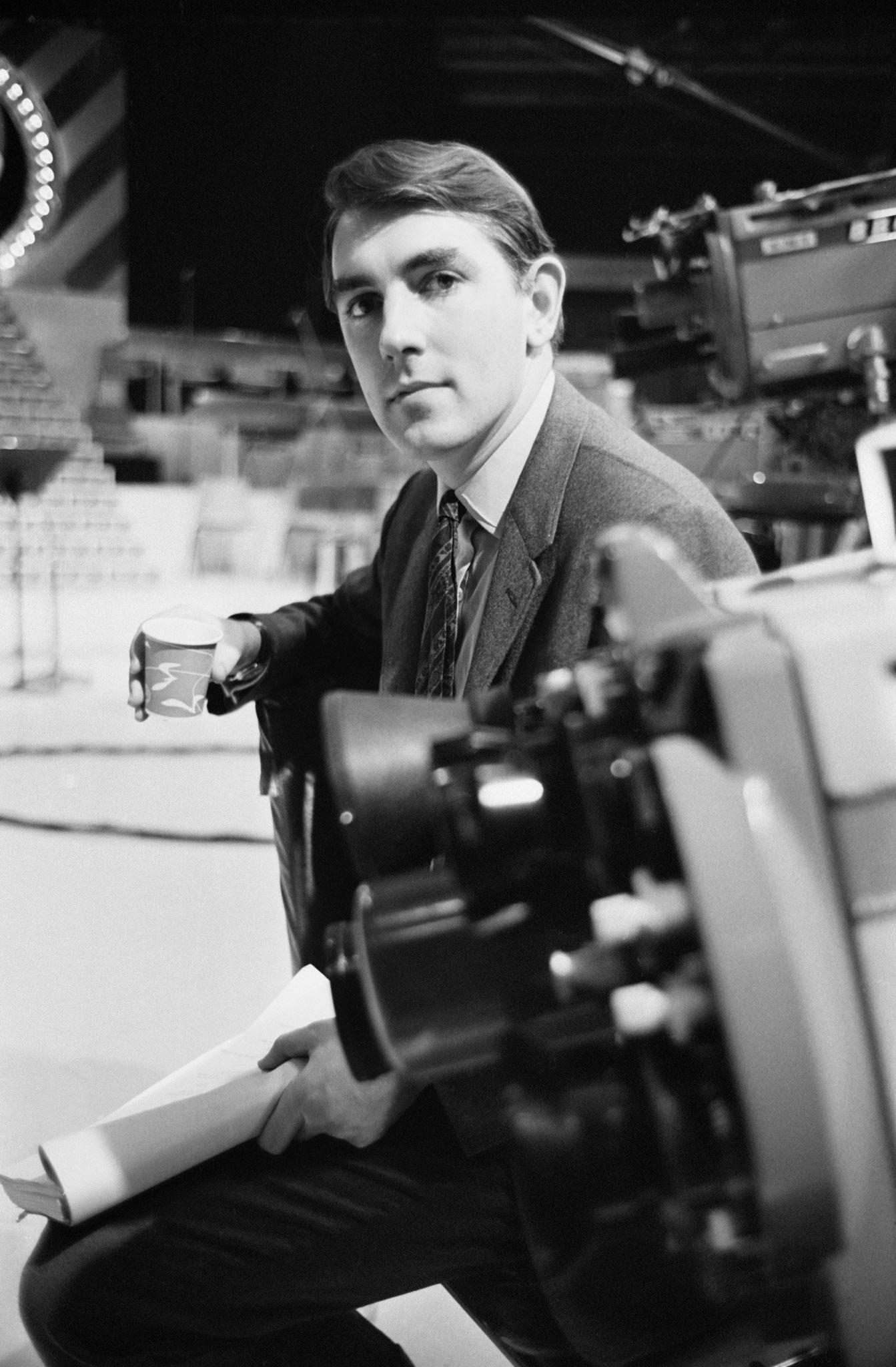

'He was clairsentient," insists Cook's first wife Wendy. "Peter could enter into another's being and reproduce their character and tone in the most uncanny way." Wendy met Peter at Cambridge, where he went to study Modern Languages (in order to become a diplomat) after his 'gap year' working as a beach photographer and travelling in France and Germany.

In West Berlin, he'd been inspired by the literary cabaret club Die Stachelschweine (Porcupines) and in East Berlin he'd got drunk, arrested and informed the police he wished to defect, because "Your cells are sooo much nicer than ours in the West".

"I believe he was sent abroad to get deflowered," says Wendy, who, while at Cambridge, Peter told of his escapades with the daughter of a top Milanese shoemaker. "He'd seen this girl, fancied her and – because he could never do anything straightforwardly – gave her a ticket to access a railway station locker where there'd be a tape she had to bring to him in a hotel room. I mean, everything had to be conducted in this MI6 way."

Cook became the most celebrated wit at Cambridge. But when visiting his father (then working for the UN in Tripoli) to spend time revising for his finals, Peter succumbed to raging jaundice. Recalls Wendy, "On his return, he quickly borrowed Eleanor Bron's notes, laid them on the floor, walked around them and seemed to photograph them directly into his extraordinary mind".

Just before his subsequent Foreign Office entrance interview, Cook was approached to perform in (and write) Beyond the Fringe. "When Harold Macmillan came to the theatre and Peter parodied and insulted him, it marked the end of the age of deference," concludes Wendy.

Yet Peter later insisted he liked Macmillan. "Well, he liked me too," sniffs Wendy, "but that didn't stop him ripping me apart. But this was a huge watershed of expansion, taboo-breaking and permissiveness. I find it amazing that with Peter I went from being a young art student to dancing in New York with Bobby Kennedy at the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis." Wendy says Cook had "a very strong sex drive" but feels he "wouldn't have dared" to have an affair with President John F Kennedy's wife Jacqueline, who often visited him. (Fellow-Fringer Alan Bennett has said he's convinced Cook did.)

Cook was carefree in his professional dealings too, when the Kray twins threatened to burn down Cook's Establishment club if protection money wasn't paid. "Peter courageously told them to piss off," reflects Wendy.

Wendy believes "Peter grew up with upper-middle-class manners and taboos and his only way to exist in that framework was humour. But later that became filth, pornography. The Derek and Clive stuff came from real repression and rather a sick mind, I think."

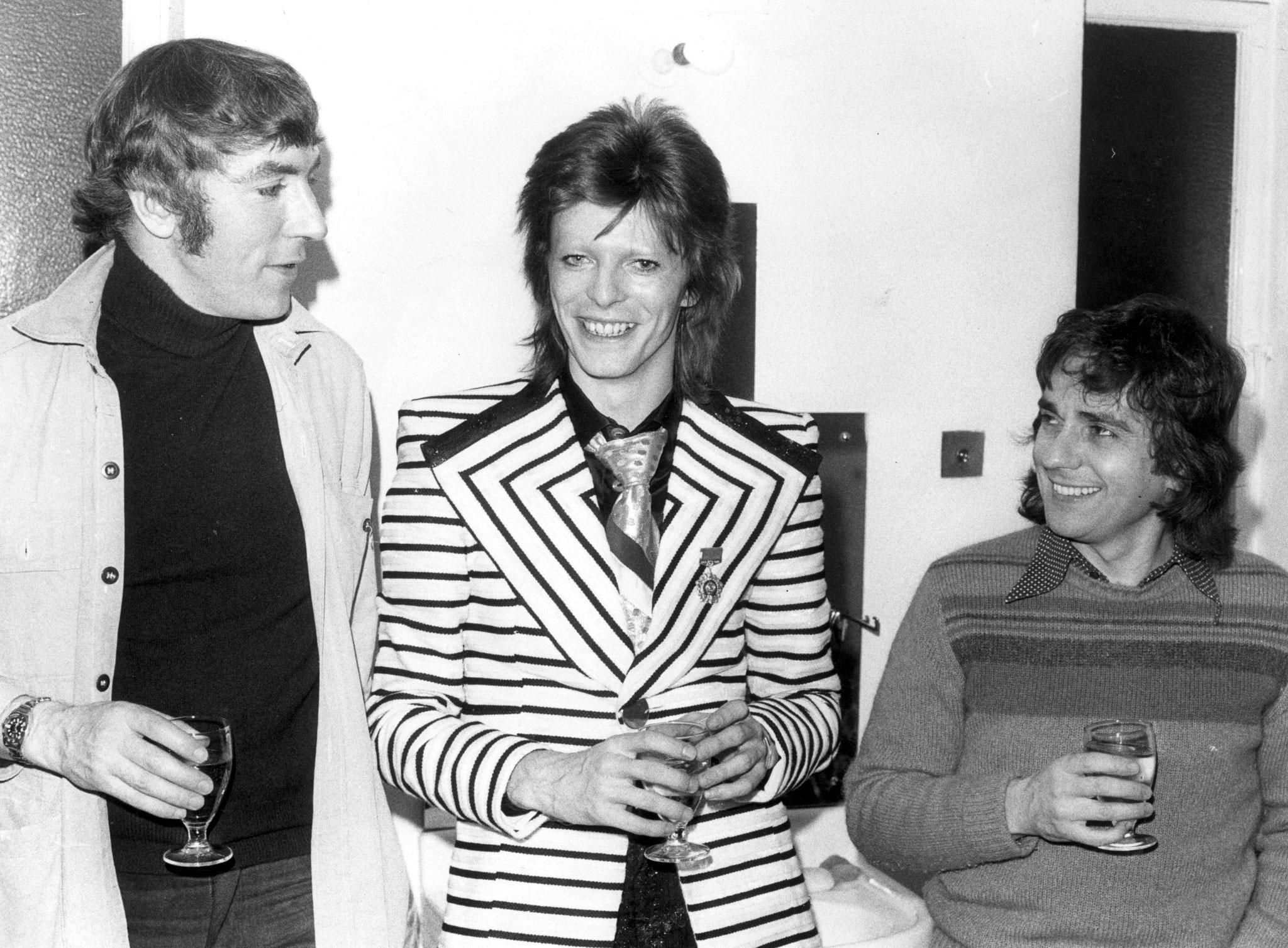

"If that was porn, it was lyrical," argues Ronnie Wood of The Rolling Stones.

"Soft and lyrical pornography which always had a point to it," stresses fellow Stone, Keith Richards. "In fact, I won't go with 'pornographic' because porn has only one point and we all know what. I think Peter was one of those guys who wanted to amuse and shake everybody up by offering the realisation of what crap we go through in life, what really goes on. And how people really speak."

Describing the Derek and Clive records as "beautiful", Wood adds, "And timeless. They're absolutely poignant; hit the nerves still. All that cancer – so terrible but so funny. They were long part of our staple daily diet. We practically lived off them – and the outtakes he sent us."

"In the middle of Oklahoma, thousands of miles from the root source," says Richards, "you can put on Pete and Dud's material, lie on the floor and say 'Talk to me, boys'."

"Peter came on my stag night," recalls Wood. "Then at my wedding to Jo he had his hand up her dress for much of the time, Jo going, 'Ooohh, Peter'. Then Peter, Keith and [Keith's father] Bert came on what constituted our honeymoon – we watched a lot of snooker in Chiswick, sound off, with Peter doing an endlessly funny rolling commentary. I especially remember him describing the audience as 'like a sedated wrestling crowd'."

"My dad [Bert]'s sense of humour was reserved for special occasions, and Peter's company was one of them," says Richards. "One day the old sod, chuckling away, explained that while I was downstairs nailing a song, he and Dud – ha, I mean he and dad – had been imagining a snooker game played entirely nude."

"Rod Stewart and I went to pick Peter up once, on the way to an Arsenal match which he pretended was Spurs," says Wood. "He'd told us he'd be by a red post-box wearing a green suit, but when we got to Hampstead he was in a red suit next to a green post-box. Peter got in the sliding door on one side of the van, then exited the other side and went straight into a pub. I used to take my secretary Doreen round to his house and with a name like Doreen she stood no chance at all. Once he threw an orange at her and I said, 'That's horrible of you, Peter'. Normally with Peter, though, I can't explain just how much he made me laugh."

Barely heard – or even heard of – are tapes of Baby Oil and The Seychelles, a group Cook formed with Ron and Jo Wood. "Baby Oil and The Seychelles were fantastic," enthuses Ron. "We did covers of The Beach Boys and his harmonies were fabulous. Or he'd take crass, horrible Jonathan King records out from his collection and we'd do covers of the B-sides. He'd change the words in funny, romantic ways, with bits of his Elvis thrown in. He'd draw, print and fax me poster ideas for our gigs – which never came off, but it was lovely."

"There was a part of Peter that wished to be a rock'n'roller, but he could never quite find the right slot," reflects Keith Richards.

Despite copies of Cook and Moore's video Derek and Clive Get the Horn having been originally seized by police, it was re-launched in 1993 – 16 months before Cook's demise – at a party at Cobden Gentlemen's Club (motto: 'Free Trade, Peace, Goodwill Among Nations'), attended by Richards and Wood.

"While most guests – loads of comedians – were waiting in the main room, we found Pete and Dud in the inner-sanctum bar downstairs drinking with working men," notes Richards. "In life, Peter generally was trying to close the gap, in himself – from where he came from and what he was about. He wanted to be one of the lads. And everybody knew he wasn't but they liked him because in a way he actually was."

"I remember us shuffling through the packed audience with Peter and Dud, to the stage and piano, for them to do their thing," says Wood. "Just as we got to the stage, Peter said, 'I don't want to do it now'. And Dudley said, 'Nah, nor do I'. And so we shuffled back to the old bar again and left the crowd with nothing. It was great."

Later that year Cook introduced some new characters on a now-famous appearance on Clive Anderson Talks Back on Channel 4. They included the rock star Eric Daley of The Corduroys and football manager Alan Latchley ("'Cause football is about nothing, unless it's about something and what it is about is football.")

Another character was Norman House, an alien-abducted biscuit quality controller who markedly resembled Cook's own neighbour 'Rainbow' George Weiss.

A decade earlier, Cook, in the guise of EL Wisty, had invented the What Party, recorded a Party Political Broadcast on Venice Beach, and recruited Weiss as his 'Minister of Confusion'.

"I could meet Peter three times in a day and be meeting three different people," says Weiss. "I did get his jokes, but I didn't really find them that funny. But once, outside in the mews, he said something which really made me laugh – I can't remember what – and then he cheered, 'I am the funniest man in the world!' and went back in his house."

Cook played a psychiatrist, "stuck in this fucking basement", to help rehearse Weiss's visit to a (real) psychiatrist, and Weiss encouraged Cook's late-night calls to LBC radio under the guise of 'Sven from Swiss Cottage', a Norwegian attempting to escape the subject of fish. In Sven's final call, Cook suggested "Give Plaice a Chance".

Weiss retains a collection of little messages sent to him by Cook on postcards. One from Mallorca complained, "Far too many fish here. Love, Sven & Jutta"; another, from Scotland, insisted "Please ignore this card". One, from the Hyatt La Manga in Murcia, advised "Re this: please see to that. Suggest you act on this later rather than sooner". Another, addressed to 'Wicked Weiss' from Porto Pollenso, reported "We're at this pesky little place preparing for Team Levy's Invincible Grand Prix Challange [sic]".

Indeed all of the cards were sent while Cook was off golfing – a passion which few grasped. "We at the Eye didn't get his golf thing, at all," says Private Eye editor Ian Hislop.

In Golf World magazine in 1993, Cook made a rallying cry for the 2001 Ryder Golf Cup to be staged across a domed Hampstead, through Highgate Cemetery, along the North Circular, then – by taxi – up to Stanmore.

One man who has fond golfing memories of Cook is Bruce Forsyth, who says "The funniest thing I've seen in my life was around the course in Gleneagles. Peter arrived carrying a bowl containing a goldfish he called Abe Ginsberg, his golfing coach. Abe was placed down beside every hole, with Peter talking to it about his technique. Peter always had strange tips of the week and once got me and everyone to play with our toes in the opposite direction to where they're supposed to point. And, frankly, it wasn't a bad way of doing it."

At Highgate Golf Club, near to his home, Cook refused to take off his baseball cap, claiming "as an Hasidic Jew" he must keep his skull-top covered. "People could get very upset by sartorial issues," says Forsyth. "Peter was very, er, relaxed, in his mode of dress. And most players will wait until the halfway hut for a drink, or hide their little flask, but Peter might carry six, eight, 10 cans of Bacardi and Coke."

In the mews (Perrin's Walk) in Hampstead, where Cook developed a fatal gastrointestinal illness in late 1994, his third wife Lin has continued to feed the pond-life which gave him such pleasure and reflection. Here, too, are his beloved Tiffany lamp, on the desk where he typed humour with two fingers, and his vast collection of sunglasses. Lin saw "at least three Wonders of the World" with Cook and is appalled by biographers' inaccuracies, such as that Cook would walk to the off-licence in slippers. "He didn't have any slippers."

Lin had met Cook at Victor Lownes' country house in 1982. He'd stumbled in late, while she was playing backgammon, and messed up her board. "Then we met again in Hampstead High Street and became friends. I had a key and would come in and do things like feed his fish. It was a pleasure whenever I made him laugh. Peter's brain was impossible to comprehend – he seemed to know about everything." (Including the names and vital statistics of every Page 3 girl.)

"Once he got satellite, Peter was rooted to the screen day and night, enjoying every sport around the world. One day he told me that, despite supporting the golfer Greg Norman, he'd had a bet against Greg, and I realised Peter always did reverse-betting. That way, if a boxer, golfer, sumo-wrestler or football team won, he'd be happy. And if they didn't he'd be happy."

Lin recalls a visit to a casino with Peter in which he lost £1,000 on a colour at a roulette table, then won £1,200 back in £25 increments.

"Afterwards, a waitress serving him a cola asked, 'Mr Cook, can you come with me? The kitchen staff are big fans'. So off he went with her and for the next few minutes laughter could be heard through the door. It turned out he'd been betting on whether scrubbing brushes, thrown in the air, would land on the bristly or wooden side."

Lin notes many opportunities and projects Cook had before his demise, including an autobiography (to be titled Tired & Emotional or 3-D Lobster), a reborn Establishment Club (in Hampstead) and a radio programme about Gibraltar. He'd been weekly improvising with Eleanor Bron for a stage show and was keen to make Peter's Hampstead, a TV show in which he'd walk around his beloved village.

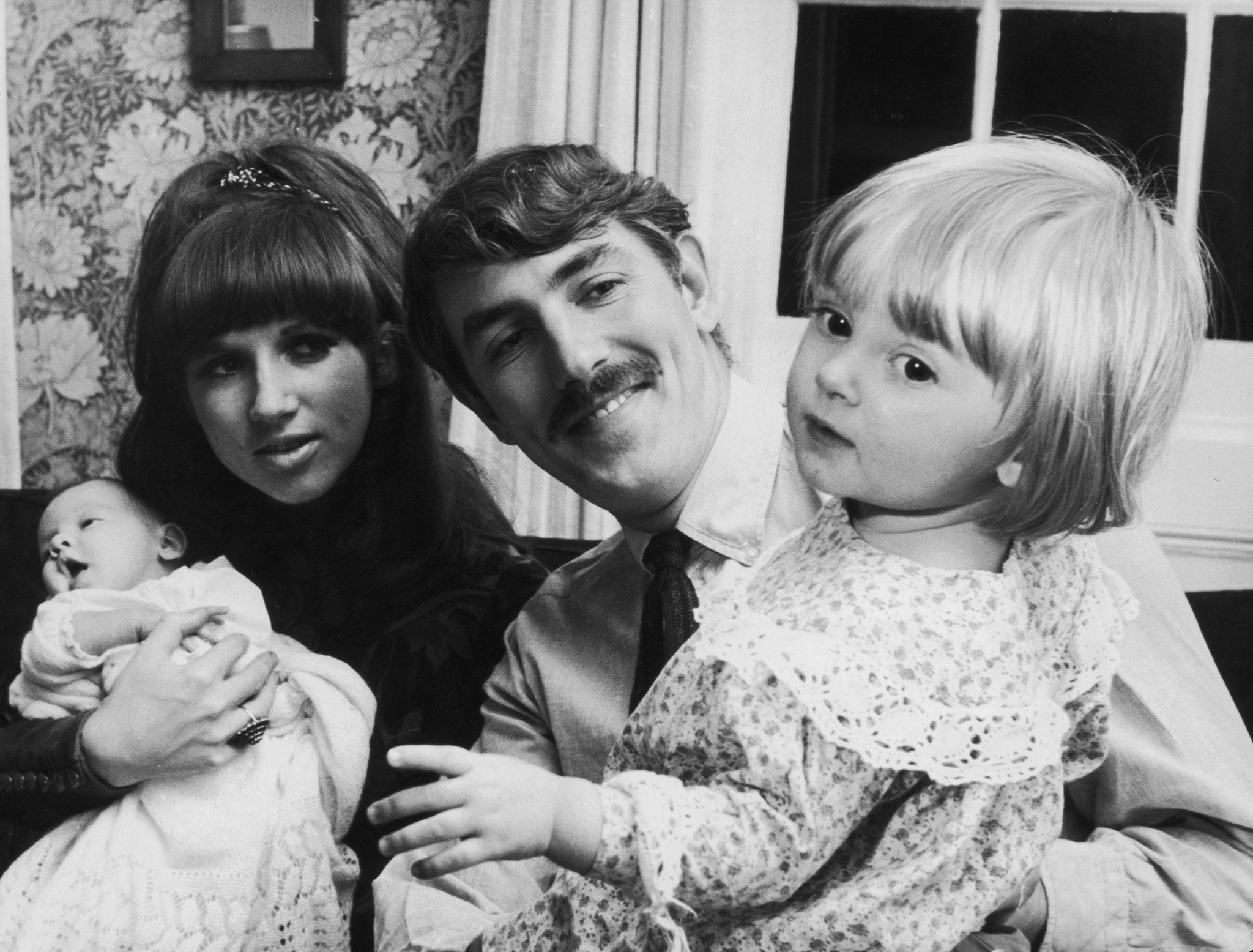

Daisy Cook, Peter's youngest daughter, has sweet childhood memories. "I remember baths in Hampstead with my sister and my dad, wearing a pair of knickers as a bath-hat, and us all collapsing in giggles. I remember him being incredibly jolly and loving. He was a very good father and would have been even better if he'd had the time and opportunity. Judy, his second wife [in the Seventies], used to call me 'Shoelaces' because I'd dissolve into tears, unable to do them up, when saying goodbye to him."

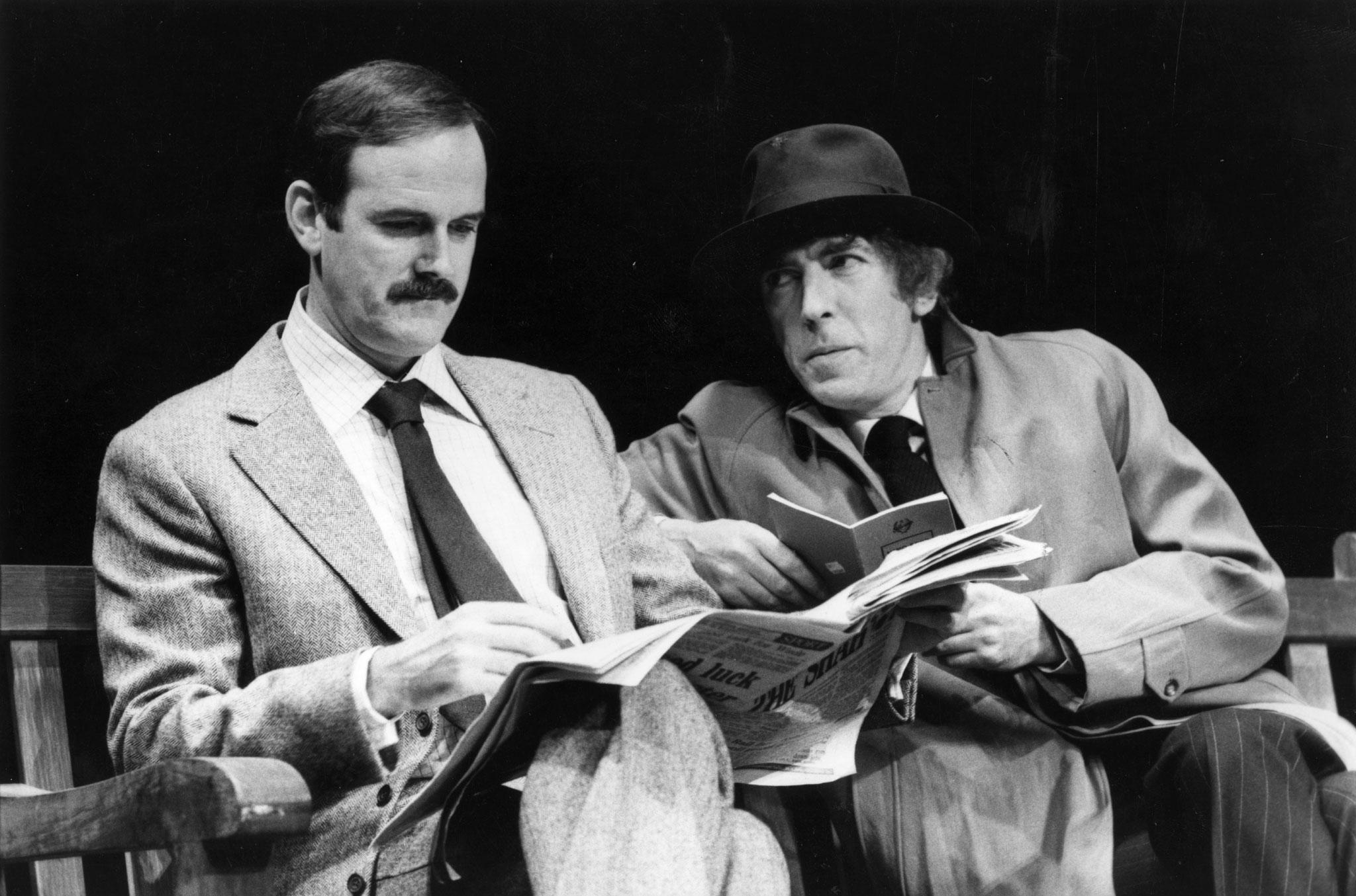

Daisy – a landscape artist with a keen laugh and also "Dad's sticky-out ears" – sits at the dinner table preserved from their years in Hampstead's Church Row, where dinner-party guests ("famous gregarious bottoms") included Peter Sellers, Kenneth Williams, Peter Ustinov, Steven Heller, John Hurt, Tariq Ali, Kenneth Tynan, Malcolm Muggeridge, John Cleese, Paul McCartney and John Lennon. When young Julian Lennon drew a portrait and was asked by his father who it was of, Julian inspired a Beatles song by replying, "It's Lucy, in the sky, with diamonds", a reference to Daisy's sister Lucy.

"She was 'Lucy Bee' and I was 'Daisy Bee'," says Daisy. "I continue the tradition with my daughter, Ellie Bee – I wanted the sound in there. Dad was always joking about bees. Judy, his second wife, believed in stroking bumble bees' bottoms.

"Dad was always up for something. There was a phase when he got into skateboarding, both on a normal-size board and a surfboard on wheels. He was very competitive but it was a hoot. We'd go [skate-]boarding with him on little windy paths around the circumference of the graveyard of St John at Hampstead, right near where we lived. We also took dolls and had nice little tea-parties, using the graves as tables."

This is the church where Cook's memorial service was held in 1995 and where he's said to be anonymously buried. Cook's demise had followed a few months after the death of his own mother ("It completely devastated him," says Daisy), but in the intervening time he'd attended – and jived at – Daisy's wedding.

"Dad did a little improvised speech in the marquee and I wish I'd taped it. He said, 'Oh, this is amazing, so lovely... the first traditional wedding I've attended' and 'All Daisy has to do now is take the tent down. But I'll be dancing until January'. In retrospect that's a bit odd, because he died that January."

As Daisy suggests putting the kettle on again, a huge bee, somewhat out of season, enters her kitchen from the garden and flies around the table, before exiting. "Look at that," she exclaims. "Was that his spirit? I wonder what it was. Because it wasn't just any bee, it was so bloody big, green and metallic. It was a killer Russian spy-bee".

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments