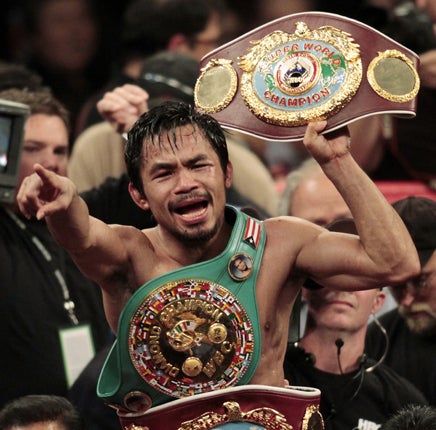

People's champ: Manny Pacquiao

He's the best boxer in a generation, and so popular Filipino guerrillas call a truce while he's in the ring. But can he be a winner politically too?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Even for a sport as famous for its hucksterism as its athletic skills, it was brave talk. Shortly before trading punches with Manny Pacquiao in the Las Vegas MGM Grand Hotel in May, Ricky Hatton attempted an ill-advised verbal KO.

The man known to millions as Pac-Man was a one-dimensional boxer, said the Pride of Hyde, unvarying and "there to be hit". "He's never met a man as fiery, ferocious or rough as me, and certainly not as big and strong," Hatton said.

As usual, Pacquiao let his fists do the talking, with a typically clinical six-minute demolition that clinched him the world light-welterweight title and helped cement his reputation as the finest boxer on the planet. A blur of crunching punches and lean, oiled power, he landed four times as many blows as Hatton, flooring him twice in round one, then knocking him out in the second round. Hatton was sent to hospital, and into a career crossroads. For the Filipino it was another day at work: "I'm just a fighter, doing my job," he said afterwards.

That typically low-key assessment vastly underestimates his lethal skills – and his status at home. Last month's destruction of Puerto Rican boxer Miguel Cotto made Pacquiao the only fighter in history to win seven titles in seven different weight divisions, and again brought his native country grinding to a halt. Crime in the Philippines plummets every time the diminutive (5ft 6.5in) boxer steps into the ring as hoods and cops huddle around TV sets, briefly united in their love for a national hero. The Philippine government, which once put him on a postage stamp, even claimed that years-long fighting between its army and Islamic rebels in the troubled south of the country stopped during the Cotto bout.

Credited with helping to resurrect a sport that had become mired in corruption and a labyrinth of competing governing bodies, Pacquiao is one those rare sportsmen, like Tiger Woods and Muhammad Ali, who transcends their profession and seems to hover in a stratosphere above other mere mortals. Now 30, he knows that rock-star popularity won't last forever, so he is re-launching a political career that could either bring him down to earth with a bump, or fulfil his promise to help the ordinary Filipinos who made him rich. Some believe he could go all the way to the presidency.

It's a long way from his humble beginnings on the southern island of Mindanao, where Emmanuel Dapidran Pacquiao was born into a typically poor Filipino family in 1978. When aged 8 he wrapped towels round his hands as if they were boxing gloves, and at 12 he happened past a television screen showing James "Buster" Douglas defeat Mike Tyson. It led him to dream. Yet the family were so poor they slept on cardboard boxes. His biographers say he ran barefoot in the hard-scrabble city of General Santos selling flowers and doughnuts until the age of 14, when he left home after his drunken, farmhand father Rosalio cooked and ate a stray dog his son had brought home.

It was also the fear of being a burden on his mother Dionisia (who hoped he would be a priest) that caused him to stow away on a boat bound for Manila, 500 miles away, where he trained in a city gym and sold ice water and doughnuts (again). He sent home whatever he earned, to help feed his five siblings. He wrote regularly to his mother, explaining that, like it did for so many poor kids, boxing offered him salvation – and an outlet for the ferocity that lurks beneath his deceptive geniality. He worked as a labourer, and fought in the illegal underground scene, where several fighters died, including friends of his. He practised using a cardboard box stuffed with discarded clothes. Two years after leaving home, and weighing a puny 106 pounds, Pacquiao won his first professional bout.

Hampered by raw, sometimes erratic performances and fluctuating weight (he has fought at everywhere from 7st 8lb to 10st 7lb), his career was not all plain sailing. After settling at 112 pounds, he won his first World Boxing Council flyweight title, then lost it in a third-round knockout. Ten pounds heavier and fighting as a super bantamweight, he took the IBF world title from South African boxer Lehlohonolo "hands of stone" Ledwaba in 2001, starting him on the road to national superstardom.

With trainer Freddie Roach by his side at the Wild Card Gym in Los Angeles, Pacquiao honed his skills, perfecting a steely left hand that has helped earn him titles in flyweight, super bantamweight, featherweight, super featherweight, lightweight, light welterweight and welterweight divisions. Those who know him say that after 14 years of professional boxing, he remains the same, slightly puzzling dichotomy: when not fighting, he is modest and easy-going, a regular church-goer and devout Catholic who rarely engages in the "dissing" of opponents so typical of the sport. Unleashed inside the ring he turns almost feral, dishing out savage punishment that is sometimes difficult to watch – one ringside commentator said Miguel Cotto's face was like "raw hamburger" after 12 rounds with the Filipino.

Like all great boxing narratives – real and fictional – success has brought the one-time barefoot street hawker wealth he once dared only dream about. He shares a huge, gaudy mansion in General Santos City on the island of Mindanao with his wife Jinkee (who met Pacquiao while selling make-up in a shopping mall), four children and a sprawling team of minders, servants, security guards and hangers-on. The commercial property he owns includes cafés, a convenience store and a souvenir shop that sells all things Manny, from dolls to DVDs.

He is a personal friend of President Gloria Arroyo (who knows the value of being photographed with him) and has met world leaders and Hollywood superstars, including Sylvester Stallone, who reportedly wants to make a movie about his life. Time magazine recently called him one of the world's 100 most influential people. As his fame grows, the purses have grown richer – the Cotto fight earned him a reported $22m before tax. Forbes magazine this year said he is the world's sixth highest-paid athlete.

After stints as an unsuccessful soap actor and even a pop star, there seems nowhere left for him to go except into politics. Few doubt his personal appeal or charisma: in one of the poorest countries in Asia, politicians and the media have lined up to praise Pacquiao for restoring some semblance of national pride. His demigod status is partly a warped reflection of the miserable lives endured by so many of his countrymen, 4,000 of whom went to the airports every day last year – about nine million Filipinos are forced to live abroad as nurses, cleaners, construction workers and prostitutes (and around 10 per cent of the national GDP comes in remittances from émigrés). But it is also a function of his generosity: he is known to spend tens of thousands of dollars entertaining guests. Ahead of a recent fight, he distributed $800,000 in tickets to friends. President Arroyo calls him "an inspiration to Filipinos around the world", a winner who returned home to share his good fortune.

Pacquiao often nods in the direction of the wretched lives he left behind. "I fight for the people," he said this year. "I want to please them and give them hope. I'm fighting for my country." But his wealth and celebrity has opened up a huge gap with the vast bulk of ordinary Filipinos, a third of whom struggle below the official poverty line of $3 a day for a family of five. Icon status or no, few observers think he has any chance of denting in the country's enormous problems unless he goes to war with its endemic corruption, and the handful of wealthy families that block reform or the redistribution of wealth.

Undaunted by a failed political bid two years ago, Pacquiao this week registered his candidacy for Senate elections, pulling up at the election office of Alabel town on Mindanao island with a convoy of supporters and 20 vehicles to register his own People's Champ Movement. As if to emphasise the corruption and political sclerosis that blights his homeland, his fellow candidates included former Philippine first lady Imelda Marcos, whose husband Ferdinand murdered opponents, imposed martial law and pilfered billions before fleeing to exile in 1986. Once a pariah, the 80-year-old matriarch is again the head of a political dynasty.

Pacquiao's friends say he is motivated less by personal ambition than a mixture of genuine concern and guilt for the people he has left behind. Above all, he knows that every boxer needs a second act. To remind him, he only has to look at skid row a few miles from his General Santos mansion, where another former world boxing champ who rose from the slums, Rolando Navarrete, now lives in embittered poverty. Trainer Roach says Pacquiao has perhaps two fights left in him, including the long-promised match-up with Floyd Mayweather Jr, likely to be one of the richest fights in history. "I would love to see Manny knock this guy out and then retire," Roach said last month. "There's no place to go after that."

If his senate bid is successful, he will then trade the ring for the infinitely more complicated world of politics. Only time will tell if he tackles it with the same ferocity he now reserves for his gloved opponents.

A life in brief

Born: Kibawe, Bukidnon province, Mindanao, December 17, 1978.

Early life: Grew up on the streets of General Santos City with five siblings. Ran away to Manila aged 14, where he worked as a labourer.

Career: Made professional debut in 1995. In June 2001, he stepped in at the last minute in an IBF super-bantamweight fight in Las Vegas, winning by TKO. Met coach Freddie Roach as a result in the Wild Card Gym in Hollywood. Beat Marco Antonio Barrera in Texas in 2003 in featherweight division. Proceeded to win world titles in seven weight categories, most recently against welterweight Miguel Cotto. Ran for a congressional seat in 2007 but was defeated.

He says: "I want to please them and give them hope. I'm fighting for my country"

They say: "He'll throw a combination at you. You'll think he's done, but then he'll keep pounding you. And there's not a dense hardness to his punch. It just jumps on you. It explodes" – coach Freddie Roach

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments