Nicola Sturgeon: Leader on slow road to her stone of destiny

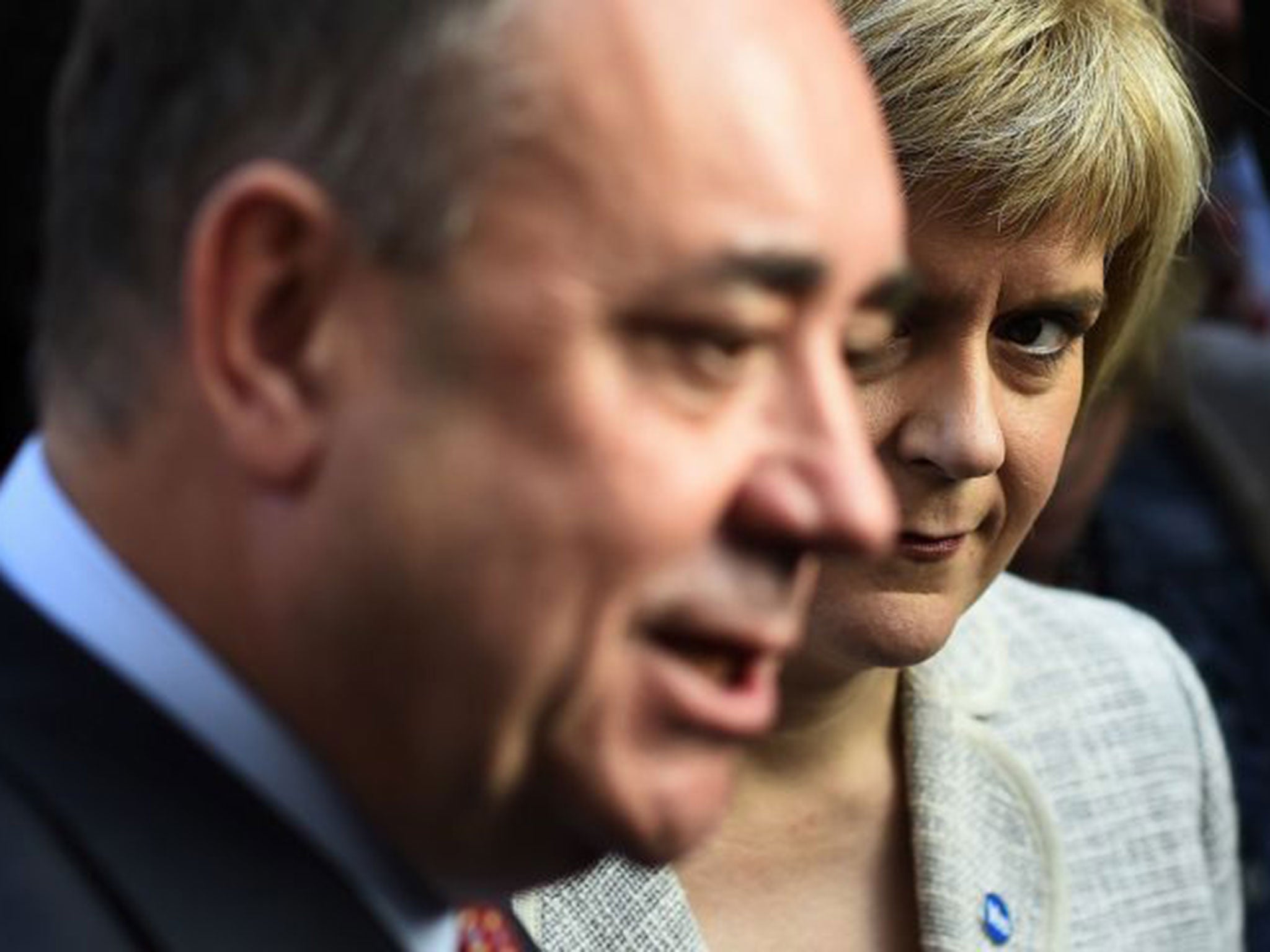

Alex Salmond’s successor as SNP leader is a less flamboyant figure, but poses an equally serious threat to the status quo

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Just a few streets away from the Perth kirk where the Reformation firebrand John Knox delivered a sermon in 1559 that sparked riots, Nicola Sturgeon will make her own history next month by becoming leader of the Scottish National Party and First Minister-elect of the Scottish Parliament.

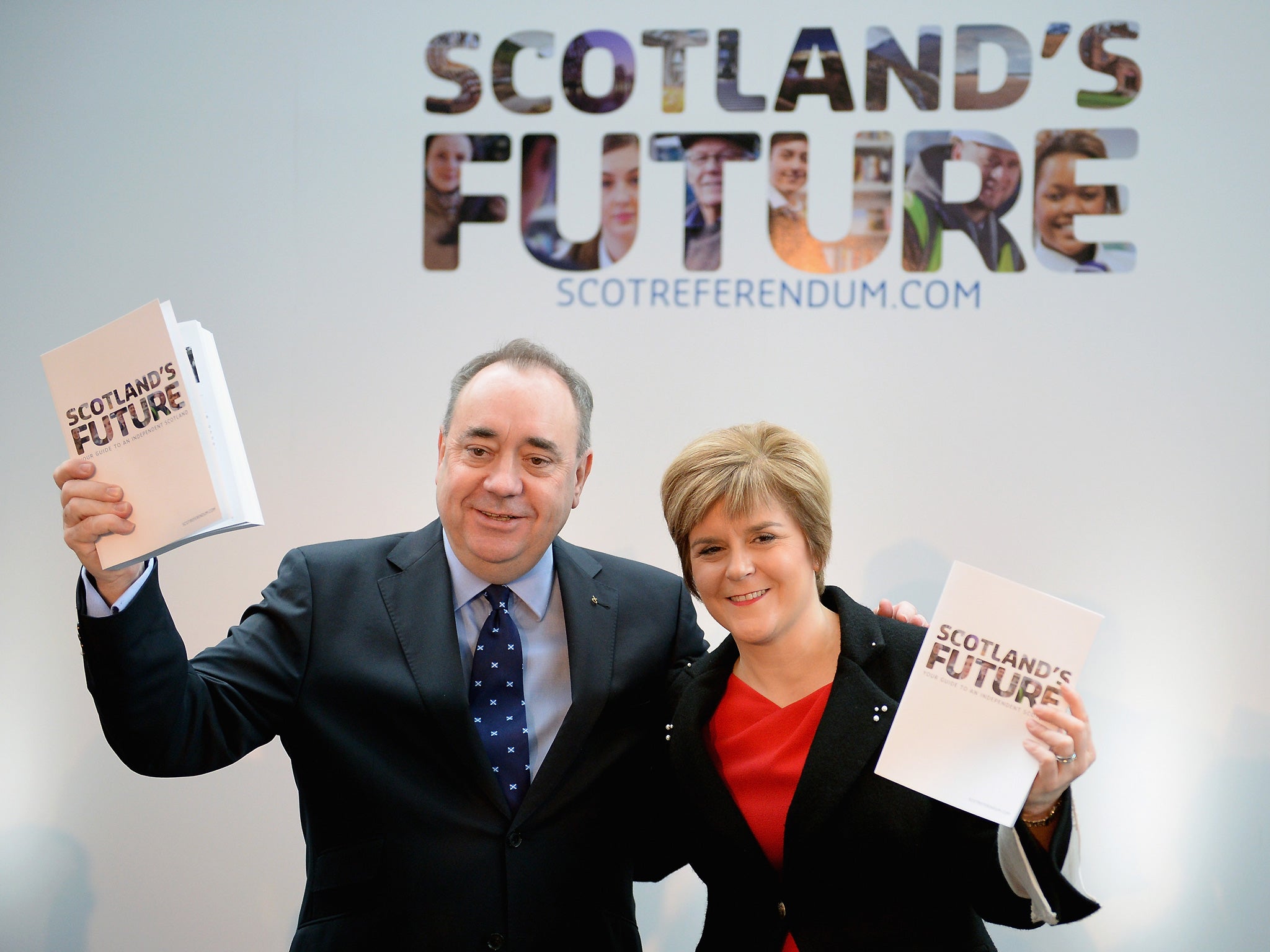

After Scotland’s rejection of independence in the referendum four weeks ago, and the surprise announcement by Alex Salmond that he accepted blame for the failed Yes campaign and was stepping down, the promotion of his time-served apprentice, Sturgeon, has been a foregone conclusion. That doesn’t make her rise to the top any less remarkable.

The unopposed coronation of Sturgeon in Perth’s Concert Hall at the SNP’s annual conference will be a blast of the nationalist’s trumpet and further evidence that another of Knox’s “monstrous regiment” has broken through to undo his warning that “the promotion of women” to rule a realm or nation is the “subversion of good order.”

Sturgeon would rather her party ignore Knox and the St John’s Kirk, and look instead across the River Tay to Scone Palace, where Robert the Bruce was crowned. If the soul of Scotland’s independence resides anywhere, Scone is an obvious candidate. It was once the home of the Stone of Destiny, the place where Scottish kings were anointed – before the English stole the stone and took it to Westminster in 1296.

The stone was returned in 1996. But Sturgeon, like Salmond, and the 45 per cent who voted Yes on 18 September, still want far more returned from Westminster than just an oblong block of sandstone or even the pre-referendum “vow” of beefed-up, enhanced powers. They still want Scotland’s sovereignty back – and one of Sturgeon’s first predictions when she learned that no one would be opposing her to succeed Salmon, was to declare: “I believe Scotland will become an independent country. That is the direction of travel… and that would be well within my lifetime.”

Sturgeon will be Scotland’s fifth First Minister since devolution was delivered by the Blair government in 1999. She’s the first woman to hold the post, completing a female trinity at Holyrood, alongside Ruth Davidson, who leads the Conservatives, and Johann Lamont, currently head of the Scottish Labour Party.

Salmond – her mentor and line-manager throughout most of her political career – predicted last week that Sturgeon would be an “outstanding” successor. Tellingly, he also said that he had no words of advice. “Nicola is well capable of dealing with any events.”

Those who have known Sturgeon since she first joined the SNP as a 16-year-old activist agree with Salmond. One of her more literary-leaning colleagues, paraphrasing Robert Burns’s poem Woman, said: “Nicola has always been ‘fix’d on mighty things”.

Others, including some opponents, point to her over-focus on political “mighty things” as a deficiency, describing her personal life, shared with her husband, the SNP’s chief executive, Peter Murrell, as a “political monoculture” where every newspaper is read and politics isn’t just a job, it’s everything.

Even in her switch-off time, Sturgeon admits that her favourite television programme is Borgen – the Scandinavian drama where the main character Birgitte Nyborg becomes the first female prime minister of Denmark.

In an interview a year after she became Holyrood’s deputy first minister in 2007, intended to show a softer side of her life with Murrell (the couple don’t have children), she nevertheless admitted that there was “downside” to the power couple’s almost total immersion in Scottish politics: “You just end up talking about it all the time, and you never leave it outside.”

“It” – the business, ambition and delivery of politics – has been with Sturgeon for most of her life. She was born in the Ayrshire new town of Irvine in 1970 and studied law at the University of Glasgow where she was active in the student wing of the SNP.

The university’s debating society has an international reputation and those who knew Sturgeon say determination rather than talent was her signature at union debates. One fellow student said: “She’d turn up every week, and every week she was utterly rubbish, leaving completely humiliated. But she’d come back, again and again, trying to get it right, determined to figure out how she could get better.”

As a qualified solicitor Sturgeon worked for a law firm in Stirling and later at a community law centre in Glasgow. She was 22, then Scotland’s youngest parliamentary candidate, when she tried to win Glasgow Shettleston for the SNP in the 1992 general election. She lost. And she lost again in 1997 when she was selected to fight Glasgow Govan.

Without the proportional representation system for the new devolved Scottish Parliament, Sturgeon’s political career would have stalled. She failed to win the Govan constituency outright in both 1999 and 2003, but was elected both times as an MSP on Glasgow’s regional “list”. She went on become the SNP’s spokeswoman on health, then education and justice.

When John Swinney announced in 2004 that he was resigning as leader of the SNP, Sturgeon’s attempt to win the leadership was on course to fail. The overwhelming favourite was the former advocate and Perth MSP Roseanna Cunningham. Although Salmond, who resigned as leader in 2000, bluntly ruled out any return, he was lobbied in the shadows to change his mind. Sturgeon withdrew her leadership bid, a Salmond-Sturgeon ticket was agreed, and three years later the SNP were in charge of the Scottish Government with Sturgeon as Deputy First Minister and a cabinet role as health minister. The hesitant but determined debater was in government.

Sturgeon is admired, rather than just liked, by both party colleagues and regular opponents. Fiona Hyslop, Holyrood’s culture secretary, describes her as “careful” and “guarded” and aware of what difficulty an answer could cause. Others have called her a “nippy sweetie”, a vernacular expression that points to an unwarranted directness.

But in the two-year run-up to the referendum, some in the SNP believe they were watching an apprentice asserting herself; moving out of Salmond’s shadow into a more self-defined role. One Holyrood insider said: “Nicola and Peter [Murrell] know they have a tight grip on the party. She hasn’t bowed down to Alex for some time now, and didn’t need to. The referendum campaign was as much hers as Alex’s – the credit and the mistakes.”

Sturgeon now finds herself head of Britain’s third largest political party after a significant post-referendum swell in SNP membership. She has a ready-made legacy from Salmond, and courtesy of Gordon Brown’s last-minute Union-saving intervention, she will be probably be in charge of a Scottish government with significant tax and spend powers. And in next May’s general election she has an already-defined target of shifting the core of Scottish nationalism from the Highlands right into Labour’s West of Scotland heartland.

For those who watched Nicola Sturgeon struggle in Glasgow University’s debates, it’s probably all a surprise. But as they say, while ambition may be path to success, persistence is usually the vehicle you arrive in.

Profile

Born: 19 July 1970, in Irvine, North Ayrshire.

Family: Her mother is Joan Sturgeon, now an SNP politician, her father Robert Sturgeon was an engineer. Married to the SNP’s chief executive Peter Murrell

Education: Greenwood Academy, Irvine before studying law at Glasgow University.

Career: Entered full-time politics as a Glasgow MSP, aged 29. Became Deputy First Minister in 2007. She will take over the leadership from Alex Salmond next month.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments