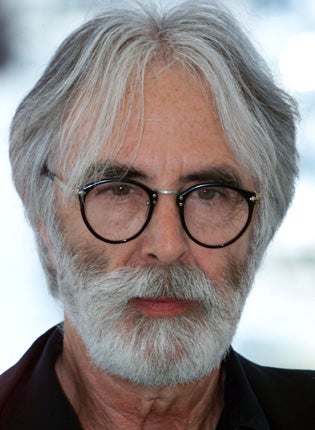

Michael Haneke: Bleak house

Audiences going to see films directed by this studious Austrian have learnt to brace themselves. His latest may be the most unsettling of the lot

For a film director who demands quite so much of his audience, and even more uncompromisingly of himself, it has taken the Austrian director Michael Haneke a long time (20 years to be precise) to gain the Palme d'Or at Cannes, that quintessential approbation of the art-house auteur. But then maybe, like Martin Scorsese's long wait for an Oscar, it isn't so surprising. Haneke is a director who challenges but he does not satisfy; his ever so precisely organised films grip you with their remorseless catalogue of pain only to leave you unrelieved at the end either by resolution or even explanation.

Not that the film for which Haneke was finally awarded the Palme d'Or, The White Ribbon – which opens in Britain next week – is any step back from his trademark grimness. Scorsese finally won an Oscar for The Departed, a work well below his best. The White Ribbon is well up among the 67-year-old film-maker's best; some critics regard it as his finest work yet.

Set in a northern German village in 1913, before a war which you know is looming but which the characters do not, it is about the relationships, society and moral decay which made it possible for German Fascists to become the ruling party of the 1930s. Only it isn't directly about that. The direct is not what Haneke is about in his films. Instead its bleak, cold narrative is an allegorical tale about the malaise underpinning society – much like most of the director's films.

The classic example of Haneke's ability to tease and to baffle was with 2005's Hidden, to date his biggest UK box-office hit. Daniel Auteuil and Juliette Binoche play a middle-class couple haunted by mysterious videotapes being sent to their house. Why they are being put on the front porch is never made clear, yet a link is made in Auteuil's mind between the videos and his belittled Algerian foster brother. The overriding sentiment is the sense of guilt that Auteuil feels about his past. But if the character doesn't understand the connections, what chance has the audience? The set-up and the story's ambiguous conclusion have been read as a comment on French colonial guilt and also a commentary on Islamic fundamentalist terrorism in a post-9/11 world, but that is a reading, not a directorial assertion.

Haneke, speaking to me after The White Ribbon's London premiere, said, "It's obviously not for me to decide what the contemporary parallels are; that is the job of the audience. Unfortunately these kinds of things [the rise of extremists] are always happening, over and over again, everywhere, and after 10 years of course there will be new examples. You could make an Arab film about Islamism and that would be a different film, but it would have the same ideas underpinning it."

The key to his oeuvre and its powerful impact is the use of off-screen space – the events that we know are happening, which the director chooses not to visualise for us. Haneke tries to engage with the imagination and subconscious of the spectator. For him a film does not start and finish with the rolling of credits. What is important is that the audience is still asking questions when they leave the cinema. He uses off-screen space to try to re-create the effect that occurs when reading literature or looking at a work of art in the gallery, where images are conjured up in the head, usually images more powerful and personal than anything he feels he can create on screen. He cites the German realist writer Theodor Fontane as a major influence on his work.

What has also become apparent in his films is that his victims are usually the weakest members of society. "On the scale of power, children are at the bottom of the pile; they are the predestined victims. Below them are animals and that is why I have a lot of animals in my film. You can see how the hierarchy of violence works. That is why women always have the best roles as well; victims are invariably the best subjects and heroes are always boring."

In Benny's Video (1992) a young girl, whose screams we hear off-screen, is shot in the bedroom of Benny. His 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance (1994) is about a mindless killing spree that takes place by chance. As in Benny's Video and his later films, images on television sets are used to comment on the influence of violent images in society, the violence of everyday and the vicious circle of violence. The failure of the family unit to provide adequate support is once again brought into focus in Funny Games (1997).

Another feature of his career is how his canvas has continued to grow and his horizons broaden in correlation with his growing reputation. The son of director and actor Fritz Haneke and actress Beatrix Degenschild, he was born in Munich in 1942 and grew up in the Austrian town of Wiener Neustadt. When his attempts to follow his parents' footsteps into acting failed, he journeyed to Vienna where he studied psychology, philosophy and theatrical studies, three subjects that combine so formidably in his oeuvre.

From 1967 to 1970 he worked as a critic, editor and dramaturg at the southern German television station Sudwestfunk. As with the British directors of kitchen sink films that appeared in the late 1960s, it was through television that he first began working behind the camera. His career in celluloid can be divided into two geographical parts. His first five films through to 1997's Funny Games were critics of Austrian society, but by 2000 he discovered the French actresses Juliette Binoche and Isabelle Huppert, and his movies starting with Code Unknown took on a more international outlook. His first major award winner was The Piano Teacher, which saw Huppert engage in gut-wrenching acts of self-mutilation.

Initially his outlook became more European until finally he turned to America in 2007. His decision to make a shot-by-shot remake of Funny Games remains the curiosity of his career and blemish on his otherwise formidable CV. What could be said of the decision to try out America is that, while his early films showed a huge breadth and depth of knowledge about the language of cinema, this was a move that showed he also had an understanding of the business of cinema. It was an acknowledgement that a film made in a language other than English would struggle to break out of the art-house market and that box-office hits and prizes help a director when they are looking for money to make their next film. Tim Roth complained that Haneke's lack of command in English – the director speaks through a German interpreter in interviews – created difficulties on set.

His directing work has also extended to the stage. He has directed work from Strindberg, Goethe, Bruckner and Kleist in Berlin, Munich and Vienna. In 2006 he took on Mozart's Don Giovanni at the Paris National Opera. He is also a professor of directing at the Vienna Film Academy where he encourages film students to create their own identities and stories on screen. With his big white beard, he looks like the stereotypical lecturer.

His next project sees Haneke return to France and reunite with Huppert. My Night with Maud actor Jean-Louis Trintignant is also coming out of retirement to play a man struggling to deal with the fact his body is unable to keep up with his youthful mind. Most of his films so far have been concerned with youth and the damage done to him. Maybe age, this time, is leading in a new direction.

A life in brief

Born: 23 March 1942, in Munich, Germany.

Education: Studied psychology, philosophy and theatrical studies at Vienna University.

Family: Has four children with his wife Suzanne.

Career: Started working as an editor and dramaturg for German television station Sudwestfunk in 1967 and made his debut as a director, After Liverpool, in 1970. His feature film debut The Seventh Continent played at Cannes in 1983. In 2001 his film The Piano Teacher won three prizes at Cannes including the Grand Jury. His biggest box-office hit was Hidden ( Caché) starring Daniel Auteuil and Juliette Binoche. In 2009 he received the Palme d'Or for The White Ribbon.

He says: "I am regarding the world around me and I have a precise eye for pain."

They say: "Film for him is an active medium, not a sedative. He wants to wake you up." Juliette Binoche, actress

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments