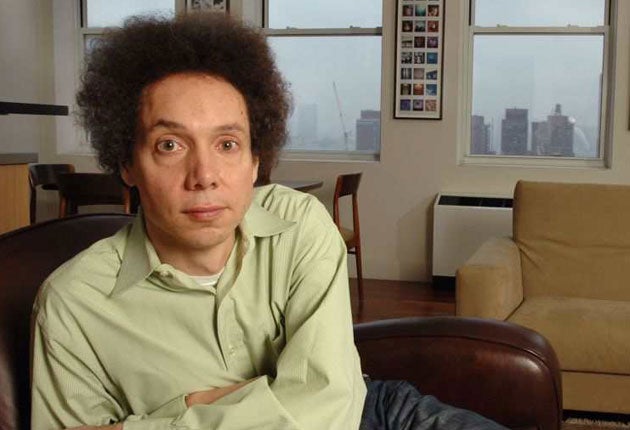

Malcolm Gladwell: Wise guy

He's been called a rock star, a shaman and a stud, but the author of 'The Tipping Point' insists he's just a journalist

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Malcolm Gladwell looks like a genius. A youthful 45, with an eclectic, vaguely hipster dress sense, a desk at the offices of The New Yorker (though he prefers to work from his apartment in Manhattan's West Village), and that signature mad scientist afro, he is a cliché of furious intellect. Yet as his latest book – Outliers: The Story of Success – demonstrates, genius is a little more complicated than that.

"Outlier", Gladwell explains, is science-speak for something that lies outside normal experience. "In the summer, in Paris," he writes, "we expect most days to be somewhere between warm and very hot. But imagine if you had a day in the middle of August where the temperature fell below freezing. That day would be an outlier. In this book I'm interested in people who are outliers – in men and women who, for one reason or another, are so accomplished and so extraordinary and so outside of ordinary experience that they are as puzzling to the rest of us as a cold day in August."

Bill Gates and the Beatles are two of Gladwell's outliers, and he credits both with considerable natural gifts. But just as crucial as their innate creativity, he says, are their circumstances. Gates, for instance, was lucky enough to attend a Seattle school that had a computer club and to live near the University of Washington, giving him access to computing equipment. The Beatles' early career was spent in Hamburg clubs, where the band had to experiment with lengthy sets.

Both conform to one of Gladwell's central arguments: that genius, or simple success, requires about 10,000 hours of dedicated practice before it can blossom, even in a gifted individual. Among the examples of the so-called "10,000-hour" rule are the late-blooming painter Cézanne and the mathematician Andrew Wiles, who solved Fermat's theorem in 1995.

In its breadth of anecdote, Outliers (published in the UK on Monday) is typically Gladwellian, an adjective coined following the wild success of his 2000 debut The Tipping Point. That book's arguments about the spread of trends ordained Gladwell as the high priest of the ideaocracy, and generated a boom in non-fiction publishing. But the book and its successors have caused controversy, too, with the author accused of profiting from the ideas of others, of sacrificing rigour for populism and, most recently, of being implacably male.

Gladwell was born in the UK in September 1963, to an English father and a black, Jamaican-born mother. Both were intellectuals: Malcolm's mother Joyce, a psychotherapist, published a book about race in Jamaica, Brown Face, Big Master, in 1969; and soon after his birth, his father Graham became a civil engineering professor at the University of Waterloo in Canada. Gladwell was raised in rural Ontario where, as a teenager, he grew into a formidable middle-distance runner, winning his age group's 1500m title at the provincial championships in 1978.

Two anecdotes from Gladwell's own early life give insight into his eclectic world view. First, he didn't own a television until his 20s, so his impression of popular culture could have developed differently from that of his contemporaries. Second, he decorated his room at the University of Toronto with a Ronald Reagan poster in an age when Canada was a rather socialist country. He later explained that "being a conservative was [a] fun, radical thing to do". Today, Gladwell is a liberal, but he had counterintuitive instincts early on.

After college, he took a job in the US at the conservative monthly The American Spectator. And perhaps in pursuit of that all-important 10,000 hours, he became a reporter at The Washington Post in 1987, eventually rising to the role of New York bureau chief. In 1996, he landed his current day job as a staff writer at The New Yorker. Offered a million-dollar advance for The Tipping Point (subtitled How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference) in 2000, he submitted a book on the cause of "social epidemics", the title of which entered the lexicon and made him the darling of the business world.

The Tipping Point primarily concerned marketing forces, discussing cultural flashpoints such as Hush Puppies footwear, the novel Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood, and the children's television series Sesame Street. Written at the height of the dotcom boom, its apparently frivolous subject matter fitted the age and his success also spawned a genre of bestselling "big ideas" books, including The Wisdom of Crowds (2004), by Gladwell's fellow New Yorker writer James Surowiecki; Freakonomics (2005) by "rogue economist" Steven Levitt; Black Swan (2007), by epistemologist Nassim Nicholas Taleb; and Nudge (2008), by "behavioural economist" Cass Sunstein. In 2005, Gladwell was named as one of the "100 most influential people" by Time. Fast Company magazine called him "a rock star, a spiritual leader, a stud".

While he may be popular with the business community and casual readers, Gladwell still faced a backlash from the intelligentsia, and from the academics whose work he had plundered. In his endnote to The Tipping Point, he cites a 1978 work, Micromotives and Macrobehaviour, by social scientist Thomas Schelling, whose findings, experts suggest, form the core of the "tipping point" theory. Schelling, a Nobel laureate, later said, "What he leaves people with is not that scientists are doing some interesting work, but that Malcolm Gladwell has a couple of good ideas."

Gladwell's second book, Blink: the Power of Thinking Without Thinking, deals with the power of first impressions, a subject its author became interested in, he said, after growing an afro and finding himself being pulled over for speeding more often. When it was published in 2005, Blink received a damning review from judge and author Richard Posner, who described it as "a book intended for people who do not read books". A spoof subsequently appeared, Blank: The Power of Not Actually Thinking at All.

His response to his critics is, for the most part, to agree with them. For an intellectual like Posner, Gladwell recently told New York magazine, reading Blink is "slumming it". The Tipping Point, too, was "a product of a lighter time". As for Schelling and his other sources, he admits, "The spotlight should be on the originator of the idea... I try to give credit whenever I can [but] the figurehead-y person with the crazy hair giving the talk, even if he tries to give credit, it doesn't stick... there's a limited amount I can do. It's a function of the way people receive knowledge."

Outliers, however, suggests a new seriousness on Gladwell's part. Rather than simply a series of stories and surprising theoretical conceits, it suggests ways in which we might harness our education systems, and our societies, to generate greater levels of success for individuals. It has a political, polemical edge to its cultural criticism, and is shorn of the marketing-man trivialities of his previous books. Yet this hasn't prevented his detractors from surfacing once again. Germaine Greer last week traduced the entire Gladwellian genre by writing that, "there is no answer to everything, and only a deluded male would spend his life trying to find it... Brandishing the 'big idea' is a bookish version of male display".

Yet controversy has never dented Gladwell's popularity. His first two books sold well over two million copies each in the US. His publishers, Little, Brown, were confident enough to offer him a reported $4m for Outliers, and he can command fees of up to $80,000 for an evening's public speaking. His British fans will have the chance to see him talk live at the Lyceum Theatre in London on 24 November. Despite all this, Gladwell refuses to describe himself as an outlier. "At the end of the day," he insists, "I'm just a journalist." But to those who devour his books, who pore over his New Yorker articles and pay a pretty penny to see him perform his intellectual leaps in the flesh, he is more than just a journalist – more, in fact, than just an outlier. To them, he is a genius.

A life in brief

Born: in England, September 1963.

Family: English father taught mathematics at the University of Waterloo, Ontario, and his Jamaican-born mother is a psychotherapist and writer.

Early life: Grew up in rural Canada, where he was an outstanding runner as a teenager. Studied history at University of Toronto, where he adopted Reaganite political beliefs that he later abandoned. After graduating in 1984, he wanted to go into advertising, but after failing to find a job decided to become a journalist instead.

Career: Moved to the US to pursue his journalistic career, with a first job at 'The American Spectator'. Joined 'The Washington Post' as a reporter and rose to become the newspaper's New York bureau chief. A staff writer at 'The New Yorker' since 1996, he is also the author of the bestselling popular science books 'The Tipping Point' and 'Blink'. Lives in New York's West Village.

He says: "People are experience rich and theory poor. People who are busy doing things – as opposed to people who are busy sitting around, like me, reading and having coffee in coffee shops – don't have opportunities to collect and organise their experiences and make sense of them."

They say: "I think what he leaves people with is not that scientists are doing some interesting work, but that Malcolm Gladwell has a couple of good ideas." Thomas Schelling, Nobel prize-winning economist

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments