Lord Young interview: ‘We need to get young children believing in themselves’

The former Thatcher favourite, and now David Cameron’s Enterprise Adviser, is convinced the link between education and business has been eroded in the rush to go to university

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When I say I’m off to meet Lord Young the reaction is universal: “Blimey, is he still going?” or words to that effect.

I can confirm that Lord Young of Graffham, David Young, is very much still going. I don’t know what his secret is but he should bottle it and sell it – for I’ve rarely seen an 82-year-old look so fit, tanned and sparky.

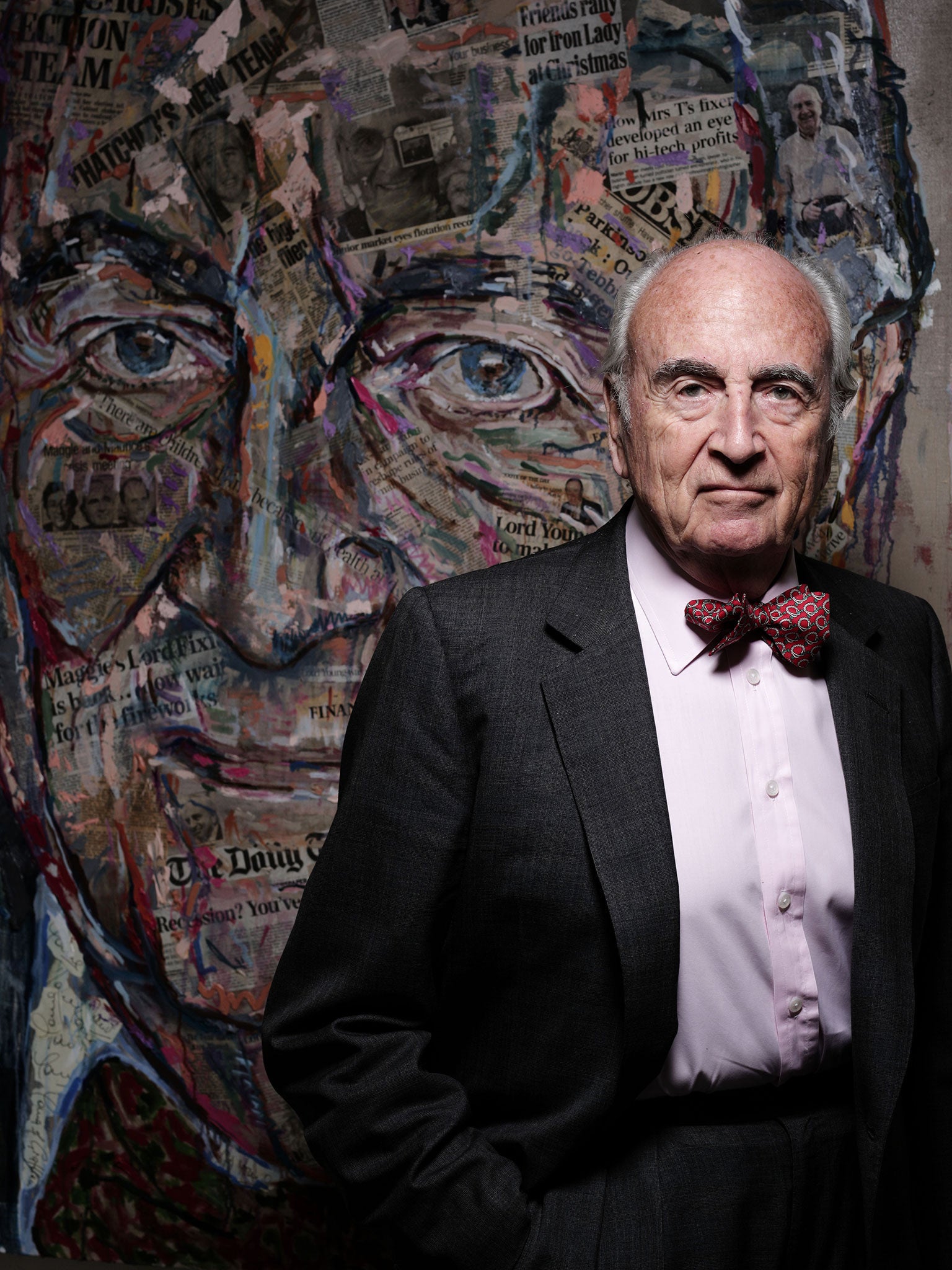

He greets me like we’re old friends. He’s all smiles, and charming. He’s wearing what has become his trademark bow tie. A red box from when he was a government minister (he was Trade Secretary, Employment Secretary and Minister Without Portfolio for Margaret Thatcher) sits discreetly on the side.

It must have been 30 or so years ago when we first met, when he was in the Thatcher government. Here he is today, David Cameron’s Enterprise Adviser. Not only is his vintage remarkable but he has the rare distinction of having resigned his post over a perceived faux pas, only for Mr Cameron to reappoint him. Most people in his position do not get a second chance – it must say something about his worth to the Prime Minister.

No sooner have we done with the handshakes than he’s away, wanting to explain what his job actually entails. “It’s about trying to get an enterprise culture into Britain.” He laughs. “The genesis of it started 32 years ago when I was introducing the YTS [Youth Training Scheme].”

Lord Young straddles the decades. Others have been and gone but he’s remained centre-stage, with his own office inside No 10. To prove the point, he adds: “Norman Tebbit [then Employment Secretary] asked me to go to the Manpower Services Commission. Youth unemployment was a big issue. I remember, I went to a factory in the West Country, and met a young man working in quality control. I said to him, ‘Were you good at maths at school?’ He said, ‘No, I haven’t got any maths qualifications. I picked it up in 10 days working here.’”

That encounter has stayed with him. “Half the children in this country don’t respond to academic education. Around 30 per cent of young people leave school convinced they’re failures. They’re going out into a life that is not going to be very comfortable for them. A lot of what I’m doing is about getting young children motivated, getting them believing in themselves.”

He’s produced four reports since taking up his latest appointment in June 2010. The first, Common Sense Common Safety, looked at the way health and safety practices stifle risk-taking in business. Then came Make Business Your Business, a detailed study of small and medium-sized enterprises and how they can be nurtured. That was followed by Growing Your Business, looking at even tinier businesses, employing under 25 people. Finally, in June this year, Lord Young published Enterprise For All and what can be done to make our education system more enterprise-savvy.

It’s based around four innovations: Enterprise Passport, a digital record of everything a pupil has done to make them more appealing to business employers; Enterprise Advisers, entrepreneurs volunteering to advise headteachers on better engagement with business and acting as mentors to children; Fiver Challenge, run by Young Enterprise; a government scheme to give primary children £5 to run mini-businesses; and Future Earnings and Employment Record, the creation of a public listing of employment rates and earnings for every further and higher education course.

“I went to state school, to Christ’s College in Finchley. I passed the 11-plus, which was a surprise. For some reason I came top at physics. I never knew why. But coming top motivated me to becoming top. I was encouraged by my parents to go and work.”

His father was a businessman who imported flour, then manufactured coats for children. After Lord Young had studied for a law degree, and worked for a time as a lawyer, he joined Great Universal Stores. In 1961, he set up his own business and built up a group of companies in property, construction and plant hire. In 1980, he sold out of all his commercial interests when he joined the government, initially to advise on privatisations.

“I was lucky because my parents encouraged me to work. But for most children that link between education and business was never present or it was broken. All civil servants came from an academic path, the majority of politicians too.”

He went to University College London, among the 7 per cent in those days who left school to go to university. “That was way too low, but we had polytechnics and technical colleges for the less academically minded.”

They were equipped to go into business and set up their own businesses. But that path was dropped, he charges, as polytechnics and technical colleges switched to becoming universities, and we became obsessed as a nation with sending more and more children to university. “It’s gone crazy. We’ve got a 50 per cent target of children going to university now which is way too high.” His latest report, he says, was the “first time anybody had looked at education all the way through from primary school to university and how that can relate to enterprise”.

He’s excited about publishing the employment rates and earnings for every degree course from every university. “No one has ever looked at them before. We ask undergraduates to make a huge financial decision without giving them the information they need. This will tell them what they can expect to earn once they graduate. It will be transformational. It’s not just confined to Oxbridge or the Russell Group but all universities – it will entirely change the game.”

Too much attention, he maintains, is paid to securing academic qualifications. “When people leave education they’re holding bits of paper, but they only have an academic value, they only tell the world about someone’s academic ability.”

That’s where the Enterprise Passport comes in. “It will contain a whole host of headings and set out a pupil’s extra-curricular experience and enterprise skills.” It’s designed to provide prospective employers and universities with something extra and possibly more relevant to go on. “They can see the whole person. It will also provide an incentive to pupils to do more.”

He’s aware, too, that state schools in particular rarely see anyone from the business community, that they don’t have business people going in and speaking to the pupils. Cue his Enterprise Advisers idea. “We’ve had enthusiastic support from headteachers and the Education Department for this. It’s all about motivating pupils, getting them switched on to the Stem (science, technology, engineering, maths) subjects which equip them for enterprise.”

He shakes his head. “A lot of the story of education over the past 30 years has been about eroding standards. We’ve got to stop that.” It’s about aspiration and self-confidence, he believes. “An entrepreneur is someone who has a go, they’re glass half-full people. I’ve never met a successful person who sees the glass half-empty.”

Producing more school-leavers for businesses is not his only target. “It’s a question of opening minds, so that someone who may be interested in medicine but isn’t able to be a doctor may want to become a radiographer, say.”

Why does he do it? Would he not rather be treading the fairways or walking the dog? He beams. “No. I sat down one lunchtime with Michael Heseltine [another octogenarian and government adviser]. We had our differences but that was a long time ago. We both said, ‘what are we doing, why are we still doing this, 30 years on?’ And you know, we both agreed it’s like a drug, we can’t stop.”

He nearly came a cropper, though, when he was quoted as saying during the recession, that “the vast majority of people in the country today, they have never had it so good ever since this recession – this so-called recession – started…” As soon as he saw his remark in a newspaper he quit, only to be rehired.

“It was taken out of context,” he says now. “Listen, I went to school in the early Forties, when doodlebugs were hitting London. You’d hear them, then duck under a desk, hear the explosion, then carry on. Imagine that happening with today’s obsession with health and safety.”

It was that he was referring to – his was a generation that had it tough. He was also thinking, he adds, of anyone with a mortgage – interest rates were so low that they were better off. But he resigned straight away rather than argue his corner. “I went as soon as I saw the headline. If I’d bluffed it out, the attacks would have continued day after day. I went, and five months later I came back.”

He is, he says, “the luckiest person in the world. I lead such an interesting life at a time of life when all my contemporaries don’t know what to do to keep their interest going.” What about retirement, surely he must be reaching the end of the road? He frowns. “No. I want to get the last report accepted all the way through.” Besides, he says, smiling, “If I keep going until eight or nine months after the election I will pass the record for the oldest person to work in No 10. William Gladstone was 83. I will pass him in 18 months’ time.” That is some record. He must have his picture taken. He brushes himself down, smooths his hair and checks his tie. Only then, ever the old pro, is he ready.

CV: Lord Young

Born: 27 February 1932

Educated: Christ’s College, Finchley; University College London

Married: to Rebecca, two daughters, six grandchildren (with one daughter he had 45 minutes’ paternity leave, with his second it was an hour)

Career: in business, property; gave it up to join Thatcher government in 1979; made a life peer in 1984; reputedly a favourite of Mrs Thatcher because he brought her solutions not problems; Enterprise Adviser to David Cameron

Private Eye nickname: “Lord Suit”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments