John Cooper Clarke: The punk poet whose time has come again

He's back: after 20 years under the radar and is embarking on a nationwide tour. His latest poetry collection is almost ready, and publishers are pressing him to write his autobiography. Nick Duerden meets John Cooper Clarke

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There was a time when John Cooper Clarke refused all requests for interviews. "Not that there were many in the first place," he points out. "But, still, I was a hermit. For years." And perhaps with good reason: the punk poet of the late 1970s whose verse was venerated by people who didn't like poetry – the best of which included the expletive-laden "Evidently Chickentown" (later immortalised in an episode of The Sopranos) and "Beasley Street" – did not fare well after punk's abrupt demise.

"The taint of punk was the kiss of death once the 80s arrived," he says now, happy to talk, not only because he has a tour imminent – including an appearance at London's Southbank Centre on 4 October to mark National Poetry Day Live – but also a late-blooming revival over which he still marvels.

"I mean, how was I going to survive alongside bands like Wham!?"

While his star may have been rudely snuffed out by passing fashion, his addiction to heroin certainly didn't help. In the much raked-over telling of his life, the Eighties have become his "lost decade", his spiralling addiction crippling his ability to write anything at all.

"It didn't mean I'd lost my desire for work, because, if anything, there was even more reason for me to work than ever," he says. "I needed the money to go shopping, didn't I? But it was a feral time, the Eighties."

To remain faithful to the mythology he'd built up around himself, Cooper Clarke would have died a forgotten man by that decade's end. But he didn't. He spent the next 20 years touring again, always – he says – "under the radar". People started to take notice once again. Earlier this year, BBC4 made a reverential documentary about him which featured the likes of Steve Coogan, Bill Bailey and Stewart Lee waxing lyrical over his contribution to poetry, and reasserting his position as one of the greatest voices of his generation. Hearing such adulation, it was difficult not to believe that Cooper Clarke had indeed died.

"I know!" he cries. "But what an obituary! I'll be honest with you, I couldn't be happier. To hear people saying such nice things about me is a wonderful thing. Me!? It's becoming a growth industry, and I love it. Who wouldn't?"

John Cooper Clarke was born in Manchester in 1949. He was comparatively old – in his late twenties – by the time punk hit, but he looked and sounded every inch the punky malcontent, and he delivered his work with both a sneer of contempt and the kind of relish that comes only when you know just how furiously funny you are. He resembled a young Bob Dylan back then; today he is more Ronnie Wood, a rail-thin 63-year-old with suspiciously black hair, styled to look like a hedge that has just withstood a hurricane. His angular face is dominated by a pair of impenetrably dark sunglasses, and his voice, genuinely a thing of wonder, is deep and heavily cracked. In every utterance lies evidence of too many cigarettes smoked a little too hungrily. He pronounces his words slowly, as if in thrall to each individual syllable.

"On my forthcoming tour," he says, "I'm doing new stuff only. I don't normally do requests, unless I'm specifically asked for them." He waits a beat, then dissolves into lugubrious laughter.

It is often said of Cooper Clarke that the real reason for his wilderness years is that he had more talent than ambition. He takes this, now, as a compliment, but argues that he always considered himself ambitious enough – for a poet.

"Poets are supposed to be underappreciated, don't you know? There is always a strange reaction to those who become successful in their own lifetime, and so I always felt lucky that I made the living I did out of it. I was convinced I'd be rumbled, and would have to go out and get a proper job."

That never happened then, and it isn't about to now. His renaissance came about in a delightfully unexpected way: certain children who had grown up on his poetry went on to become teachers and managed to get several of his poems – including the memorable "Twat" ("You're like a dose of scabies / I've got you under my skin / You make my life a fairytale … Grimm!") – on the GCSE syllabus. Alex Turner of Arctic Monkeys studied them, and now cites Cooper Clarke as his main inspiration, his living hero.

"I met the lad [Turner] about two weeks before they went global," Cooper Clarke says. "I'd just done a show and was out the door, when the proprietor told me that some lads in a band wanted to meet me: they'd done my stuff at school. I asked him what they were called, and he said Arctic Monkeys.

"Immediately, I thought: here is a band speaking my language. There's a whole wide world in those two words; it prompts an emotional response. Think about it. Arctic Monkeys; a monkey in the Arctic. That's terrible! I mean, good Lord! Get that monkey out of there!"

The pair struck up a firm friendship, and barely a month has gone by since without another modern-day comic, actor, or singer-songwriter paying very public homage to the man. Earlier this year, he made a cameo in songwriter/director Plan B's debut film Ill Manors, and also guested on the soundtrack.

"I was a bit nervous of doing it at first, because I'm not quite au fait with that whole white Jamaican east London patois thing," he says. "I didn't want to look like some old twat running to keep up with the kids of today but, at the same time, I didn't want to look like yesterday's news, either."

And so he went a different route altogether, his spoken-word monologue on the track "Pity the Plight" carrying an almost Victorian tone:

Pity the fate of young fellows

Too long abed with no sleep …

Their Christian mothers were lazy, perhaps

Leaving it up to the school

Where the moral perspective is hazy, perhaps

And the climate oppressively cool.

"Lovely fella, Plan B. People think his success is overnight, but it isn't. The boy works hard. I did, too. It took me 30 years for people to consider me an overnight success …"

But success, he insists, has not changed him. He still lives, with his second wife, Evie, and their teenage daughter, Stella, in Colchester, Essex, where they have spent the better part of 20 years.

"Don't get me wrong, I'm not waving the victim's flag," he says, "because life is pretty good, but I'm not quite as famous as I think you think I am."

Nevertheless, momentum is building. He is working on a book of poetry, and publishers are pressing him to write his autobiography. Cooper Clarke, much the same punky malcontent he ever was, says he can't be bothered. "Where's the mileage in an autobiography? Anyone who writes one inevitably casts themselves as a hero, and I'm not about to do that. No, I'd much rather they made an inaccurate biopic of me starring someone wholly inappropriate, or else someone writes an unauthorised biography."

And the more scurrilous the biographer, he cackles, the better. "Do you remember Albert Goldman? [a somewhat sensationalist biographer whose subjects included Elvis Presley and John Lennon]. His books were always met with a barrage of writs and lawsuits, even before publication, and reliably stuffed with controversy. That's the sort of treatment that would do for me."

Curriculum vitae

25 January 1949 Born at Hope Hospital, Salford, Lancashire, to Hilda, an unpublished poet, and George, an engineer. Attends St Andrew's school.

1970 Marries first wife, Chris, and moves to Shaftesbury, Dorset. They separate three years later and Clarke returns to Manchester.

1976 Begins performing at concerts in the Manchester scene as a "punk poet". In October the following year, releases his first EP, Innocents, on Rabid Records.

1979 Releases only UK Top 40 hit, "Gimmix! (Play Loud)" and joins Equity under the name Lenny Siberia.

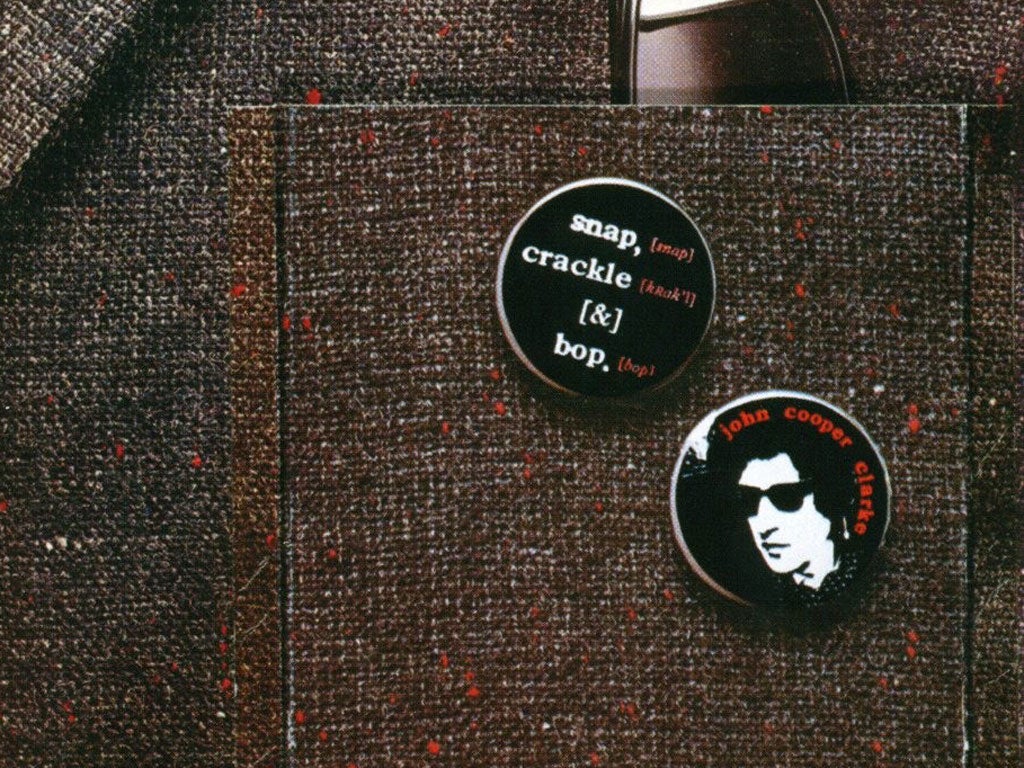

1980 Highest-charting album, Snap, Crackle & Bop, reaches No 26 in charts.

1980s Lives with Nico from Velvet Underground in a "domestic partnership" in which they share an addiction.

1982 Performs "Health Fanatic" in music documentary Urgh! A Music War. Stars in John Cooper Clarke - Ten Years in an Open Necked Shirt, a Channel 4 documentary.

1988 Appears in two Sugar Puffs commercials alongside the Honey Monster.

1989 Marries Evie, a language teacher from Picardy.

1992 Finally gives up heroin.

2007 His track "Evidently Chickentown" is used in an episode of The Sopranos.

2012 Appears as himself in Ill Manors. Performs "Pity the Plight of Young Fellows".

May 2012 Is the subject of BBC documentary Evidently … John Cooper Clarke.

John Cooper Clarke's nationwide tour begins on 29 September. Details on www.johncooperclarke.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments