Jim Broadbent: Dementia, even among the famous, shouldn't be a taboo

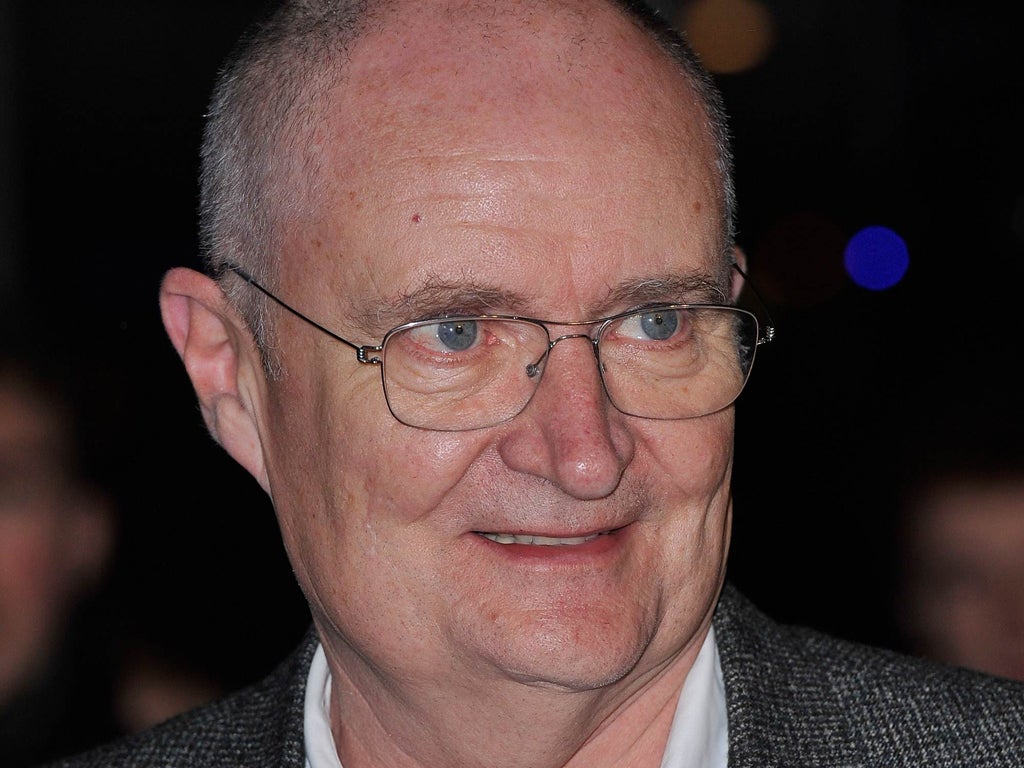

The actor, who plays Denis in 'The Iron Lady', rejects criticism of Meryl Streep's portrayal of an ailing Margaret Thatcher as 'ghoulish'. She humanises the former prime minister, he says. Genevieve Roberts meets Jim Broadbent

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Jim Broadbent is bemused. The controversy surrounding The Iron Lady, which opened last week and in which he plays Denis Thatcher, is simply beyond him. Meryl Streep's portrayal of Margaret Thatcher, stricken by dementia and caught in a world where her – deceased – husband is still her companion, has been criticised by David Cameron, who suggested a film biography should have been held back until after her death. The former foreign secretary Lord Hurd described it as "ghoulish".

"I don't really get it," Broadbent muses. "I think it's good that dementia is up for discussion. It's about taking away the taboo and fear of it, acknowledging it as a condition which so many of us have experienced and will experience. With any other disability, such as a physical disability, that would be up for grabs, but there's still some sort of resistance to mental illness being shown: people think it's intrusive, but I don't; I think that shouldn't be the case really."

It's not the first time he has starred in a film that deals with dementia; Mike Leigh's Iris, about the novelist Iris Murdoch, was one of the first films to discuss the subject openly. "All the dementia charities were delighted – there was a great reaction to the film. The public were left feeling able to go to charities and discuss it, feeling that it wasn't something with any degree of shame about it."

It is a subject he feels strongly about, but Broadbent sounds considered rather than passionate. He certainly could not be accused of ranting.

I meet him in the Soho Hotel and somehow expect his real-life persona to be similar to his character of Bridget Jones's father in the films (he tells me a third, featuring Bridget-with-baby, is now on the cards). But Broadbent, who won an Oscar for his portrayal of Murdoch's husband John Bayley in Iris, is far less jocular and animated than Mr Jones. He is polite and answers all my questions, although it's almost as if he's consciously willing himself to end sentences that would otherwise trail off. And he seems reserved: I feel he's responding almost out of a sense of kindness and would be just as happy to sit in silence.

If he really is a quiet man, and not simply tired or averse to interviews – although he tells me he "quite likes them" – then it is another testament to his skills as an actor, as he has so much fire on screen.

His language reveals a passion that contrasts with the calmness and frequent pauses in his responses. He thinks The Iron Lady is "terrific", and really enjoyed it. "The script was intriguing and interesting. Working with Meryl was a delight; she is extraordinary, pure talent," he explains.

His admiration for Streep is matched by his disenchantment with Thatcher. But his perception of her as a person changed while he was working on the film.

"It has humanised her in a way, because she was such a two-dimensional totem which you either loved or loathed. I think that's particularly so with the vulnerability that comes with old age and dementia," he says.

It's unsurprising that his views – although he says he's not "hugely political" – are not in line with the Tories. He was brought up by liberal, pacifist parents in Lincolnshire. "I see myself as a small 'l' liberal," he explains, pausing before adding, "but not coalition liberal, necessarily."

And he respects the first female Prime Minister for standing up to be counted. "She didn't prevaricate; she said what she thought. Whatever you thought of her policies, she was an honest politician. Weasel words weren't her way. In today's politics, it would be good to have politicians who are more upfront about what they felt and actually not trying to bend with every breeze. They're infuriating, all of them."

His mother was a sculptor, his father a furniture maker and artist. "It's always been a given that being creative would be my first option, really. Find out what you want to do – rather than what you have to do."

He says the parental template he was given wasn't to get a job first, and be creative as a hobby, and he was lucky that he was encouraged to do anything he wanted.

He studied at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art some 40 years ago, and his career has grown steadily since. "I was told I would probably be into my 30s before I started doing well, which was probably accurate."

But when he started doing well, it was with conviction. He has had roles in dozens of critically acclaimed films, working with Mike Leigh on Life Is Sweet and Topsy-Turvy, as well as Another Year in 2010. And when Broadbent wrote the short film A Sense of History in 1992, Leigh directed it. He's had roles in Moulin Rouge and the Harry Potter films, and his everyman face has become a British institution.

Despite this, he says he leads a normal life. "I like being able to go to the supermarket and go on the Tube and have an ordinary domestic life. I'd hate to have to protect myself. I'm quite lucky that I can carry on without any intrusions. I don't get given a hard time by anyone," he says. "People smile at me as if they know me. I just smile back. They probably might know me."

When he's not acting – and he is choosy about the roles he accepts ("I never want to repeat myself," he says) – he spends time with his wife, Anastasia, a painter, in their homes in London and the Lincolnshire countryside. And he likes woodcarving. "I make figures: it's another way of creating characters, really. There's a whole gang of them. I don't know what I'll do with them."

At 62, he explains that his love of acting has evolved: "I'm still as interested, I suppose, but not as passionate. To start with, it's such a new and exciting game; it's like a new love affair. You are obsessed with it. It settles down to something you have a more considered attitude to. It's harder, I suppose, to find really interesting projects. When one comes along, like Cloud Atlas, I get really excited."

He has just finished working on the film, based on David Mitchell's novel, which takes the form of six linked stories. "That was as exciting as it was getting jobs in the early years," he says, with more passion. "That was an amazing project, with Andy Wachowski directing three of the stories, and Tom Tykwer, a German director, directing the other three. The principal actors were in all six stories, all playing different parts."

And then there's the possibility of a new Bridget Jones too: "I think I'll be doing that before long, not that it's been confirmed yet." But he's conscious of getting a balance between work and leisure, working only as much as he wants to. And he can afford to be picky.

"I've done so much, but I'm always looking for things that I haven't done before. You become more choosy."

And he's conscious, having played John Bayley and Denis Thatcher, that he doesn't want to play too many roles older than himself. "I'll try to stop that as the years are coming anyway," he says.

Having played two roles that tackle dementia, does the prospect of ageing scare him? "As much as it does anyone," he admits. He pauses, then qualifies, quietly: "No, it doesn't scare me. It's depressing, I suppose. You become more aware of it as you get older."

Curriculum vitae

1949 Born in Holton-cum-Beckering, Lincolnshire.

1972 After attending Leighton Park, a Quaker school in Reading, he graduates from the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art.

1976 His stage breakthrough comes in Illuminatus, a 12-hour science fiction play in which he plays a dozen characters. This is followed by work with the National Theatre of Brent.

1978 Film debut in Shout, before a substantial TV career, including Only Fools and Horses and Blackadder.

1987 Marries Anastasia Lewis, a costume designer he met four years earlier.

1990 Big breakthrough comes in Mike Leigh's Life Is Sweet, before appearances in The Enchanted April and The Crying Game.

1992 Writes and stars in A Sense of History, directed by Mike Leigh.

1999 Working relationship with Leigh continues in Topsy-Turvy, for which he wins the Volpi Cup for his portrayal of WS Gilbert.

2001 Appears in three of the year's most popular films: Bridget Jones's Diary, Moulin Rouge and Iris, for which he wins a Golden Globe and an Oscar for best supporting actor.

2006 Wins another host of awards for Longford, in which he plays Lord Longford.

2009 Appears as Horace Slughorn in Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince.

2012 Plays Denis Thatcher in The Iron Lady, and then in Cloud Atlas.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments