Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Hell might not quite have frozen over, but some great climatic sea-change must have occurred to affect the reunion of The Stone Roses, announced this week to a mixture of astonishment and glee from the band's fans.

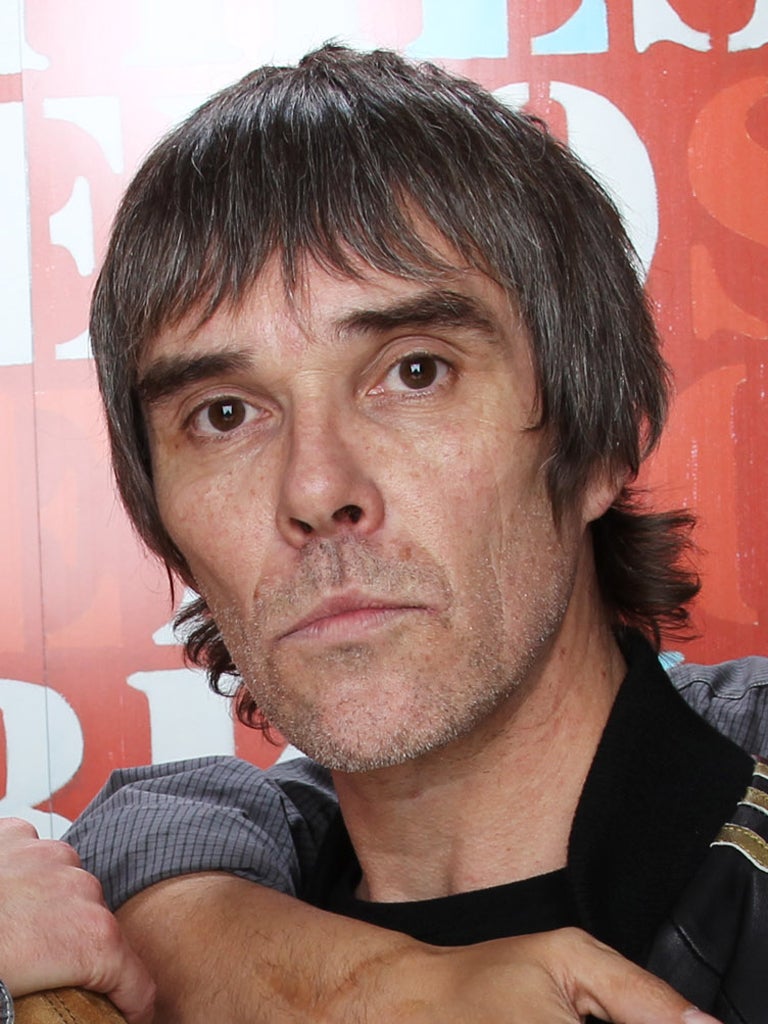

And given that the group's creative core of singer Ian Brown and guitarist John Squire had at one point not spoken for about a decade, it does seem a more surprising reunion than most.

The Stone Roses were one of Britain's most iconic groups of the post-punk era, their shuffling indie-dance grooves suggesting a route out of the grey indie mire into which "alternative" music had slipped towards the end of the 1980s. The brooding but melodic acid-rock of their eponymous 1989 debut album, since voted the Greatest British Album Ever in one magazine poll, offered a breath of fresh air that served to inspire a generation of Britpop bands, notably Oasis, whose Gallagher brothers extended further the lippy Mancunian self-assurance which Ian Brown had displayed in songs such as "I Am The Resurrection" and "I Wanna Be Adored".

The attitude extended beyond the songs, too: whenever they became involved in business disputes with former managers, recording studios, and record labels, The Stone Roses were as likely to take direct action as consult lawyers, in one case throwing paint over a label boss who accompanied a reissued single with a promo video they disliked. It was their seemingly interminable dalliance with m'learned friends over a wide range of matters – some delinquent, some contractual – which delayed the release of the band's follow-up album, whose modest title The Second Coming rebounded on them when its ersatz heavy-rock was poorly received. In their absence a succession of music trends – grunge, hip-hop, techno, retro-rock, trance/ambient – had displaced the "baggy" indie-dance scene upon which The Stone Roses first floated into view, and a series of generational spokespersons and Next Big Things such as Nirvana, Suede and Oasis chipped away at their constituency.

When The Stone Roses broke up shortly after, the accepted view was that John Squire, a gifted guitarist, would have no problem developing a new career, whilst Brown, the non-musician who couldn't play a note, and often struggled to sing in tune, would end up on the rock'n'roll scrap heap. The reversal in their fortunes remains one of rock's most impressive transformations, Brown teaching himself from scratch how to play guitar and write songs, using a blues songbook and a Bob Marley songbook as guidance.

"I used to work out the vocal melodies on a little Bontempi wind organ," he explained. "That's why they all sound sort of hymn-like, because everything sounded like Fight The Good Fight on this little Bontempi organ."

Before long, he had acquired enough rudimentary musical skills to write the songs that made up his debut album Unfinished Monkey Business, a surprisingly impressive collection of swamp-funk and dub grooves. It was immediately clear that despite the obvious shortfall in natural ability, he possessed the greatest musical ambition of all the band's former members.

Brown was born in February 1963 in the Lancashire town of Warrington, midway between Liverpool and Manchester, and was subsequently brought up in the Manchester suburb of Timperley. His father George was a joiner whose socialist leanings – he describes him as "a bit to the left of Arthur Scargill" – made a sizeable impression on the youngster, as did his own youthful fascination with charismatic outsider heroes such as Bruce Lee, Muhammad Ali and George Best. "My dad brought me up to follow no man," Brown once told me. "I was brought up to believe that all monarchists are thieves, and that we're all slaves to society."

This anti-establishment, pro-proletarian attitude runs like a thread through all his half-dozen solo albums, often in dialectical conflict with a willful arrogance born out of his natural Mancunian self-belief.

In his earlier work, he often lapsed into clichéd denunciations of war monger and money grubbers, but by his fourth album Solarized, Brown was creating sharply-wrought lines like "Oil is the spice to make a man forget man's worth". Like many an intelligent lad who left school too soon, as an adult he became something of an autodidact, with a particular interest in his country's colonialist past. He was especially impressed by Marcus Garvey's biography, marvelling at the black nationalist's ambition: "Amazing – 22 years old and he's trying to unite Africans worldwide."

Like Garvey, Brown was sentenced to time in jail – though not for his high-minded beliefs, simply for an in-flight fracas with cabin crew that he maintains was blown out of proportion. His two months spent in Strangeways Prison he subsequently attributed to his failure to acquire an expensive London lawyer. "I got a backstreet lawyer from Manchester because I was advised, You don't want to get a big London silk down, they'll think you're being flash."

While unpleasant, his time inside passed peaceably enough, though his celebrity caused problems for the authorities, who kept moving him from wing to wing.

Pop stars in prison can be targets for notoriety-seekers, but fortunately, he was threatened only once, and was heartened to find himself protected by fellow inmates. "I was touched by the way kids looked after me inside," he recalled later. "They'd give me coffee and sugar and newspapers and apples and tobacco and phonecards." In any case, Brown could probably have taken care of himself, having had many years' karate tuition.

After his release Brown continued to mature, the twin powers of parenthood (he has three teenage sons) and sobriety supplanting the rock'n'roll attitude. Although there remains a touch of the old arrogance: when he sponsored his local football team Chiswick Homefields for a season, the team's shirts bore the legend "IB –The Greatest". He has also become a deeply spiritual man, albeit on his own terms. "I believe in the spirit," he says. "All the great tribes, through time, have all got it down to the one spirit – the Aborigines, the Incas – all the prophets believed in the one God. But the organised churches have hijacked religion off all of us, they've stolen God from us, they've put the priest next to God." He freely admits there may be a bit of the hippie in him, but he resolutely rejects the idea of dropping out of society: "I believe in getting in the middle there and trying to change it."

Certainly, there has been no excess of material ambition involved in Brown's career. His own albums and tours have performed well, but in sheer commercial terms The Stone Roses were a disaster. They turned down such obviously remunerative possibilities at large venues such as the iconic north London venue Alexandra Palace and when they did organise a large one-off show, at Spike Island, in Widnes, they ensured the ticket price was kept low enough – a mere £13, cheap even back then – for fans to easily afford, whilst allowing the band to break even. "We did so many things like that where we weren't chasing the dollars, that now I think if we didn't get paid, it's because we didn't chase them," he later reflected. "But if you chase a dollar, it'll blow away; if you do your own thing, it might come."

But while the extraordinary demand for tickets for the forthcoming Stone Roses shows – 150,000 tickets were sold within a quarter of an hour yesterday – confirms Brown's appeal among his own generation, to younger kids he may be better known for his brief cameo as a bohemian wizard drinking in the bar at the beginning of Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. Not that it prompted a desire to change the course of his career. "It didn't give me a taste for it," he said. "I'd rather be free and doing my own thing than be an actor. The actors don't hear the applause, do they?"

A life in brief

Born: Ian George Brown, 20 February 1963, Warrington, Cheshire.

Family: Son of George, a joiner, and Jean, a receptionist. Divorcing Fabiola Quiroz, with whom he has a son. He has two other sons.

Education: Attended Park Road County Primary and Altrincham Grammar School for Boys.

Career: The Stone Roses released just two albums. The first was voted the best British album of all time in 2004. After the band split in 1996, Brown pursued a successful solo career. In 2006 he was awarded NME's Godlike Genius Award.

He says: "There's more chance of me reforming the Happy Mondays than the Stone Roses." (2005)

They say: "The Stone Roses getting back together: not been this happy since my kids were born." Liam Gallagher.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments