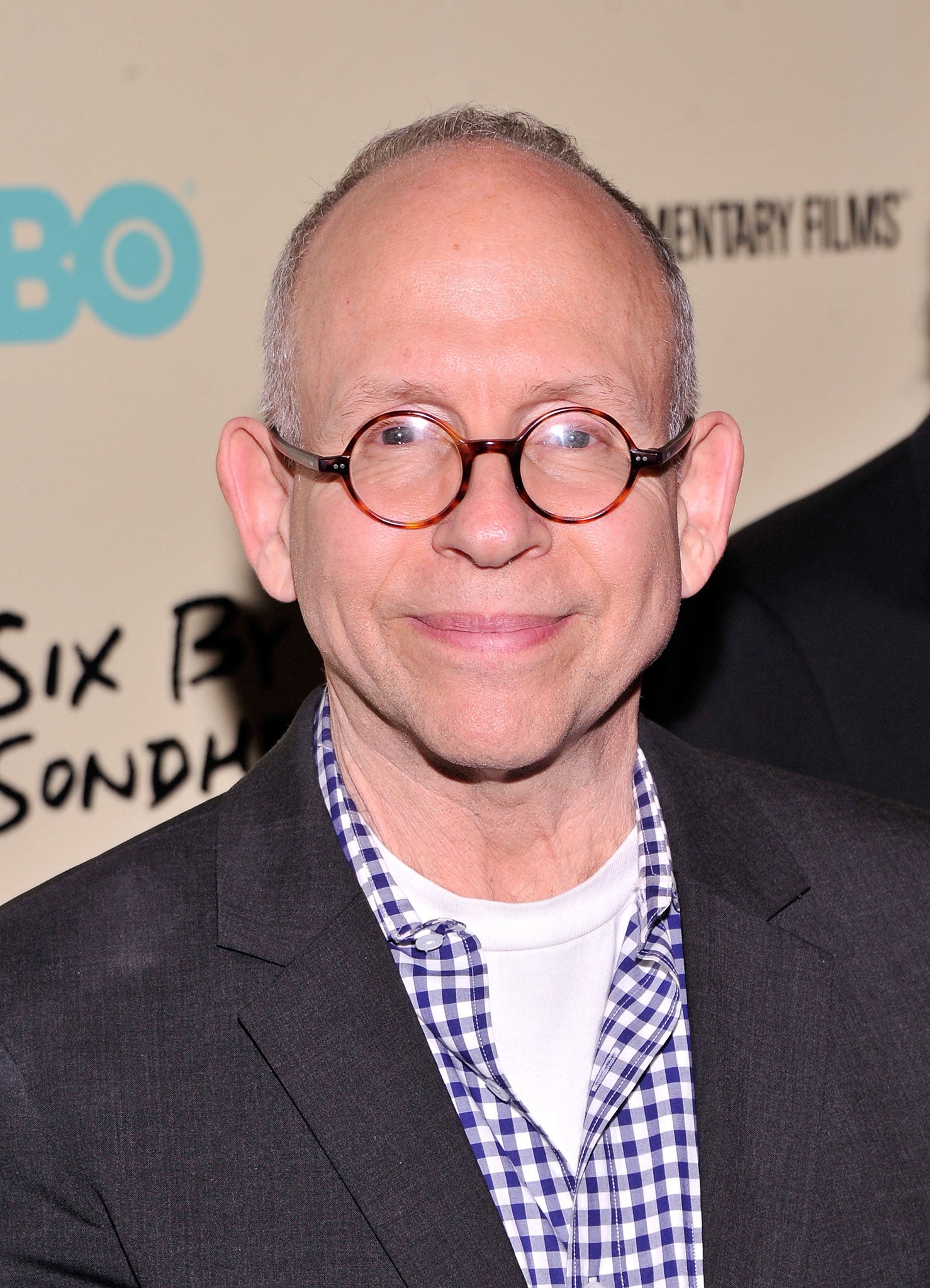

Being Bob Balaban: From Downton Abbey to The Monuments Men - is the actor the best-connected person in Hollywood?

In a career spanning some 70 movies, Balaban has worked with Steven Spielberg, François Truffaut, Mike Nichols, Ken Russell, Orson Welles, Woody Allen, Robert Altman, Wes Anderson and Christopher Guest. And those are just the directors

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.You'll recognise Bob Balaban, even if you can't quite figure out why. He's that actor, from that film. Or wait, was it a TV show? Oh, you know: the guy with the glasses! He plays neat, petite, polite New Yorkers not unlike himself. He often sports a moustache. He is not Ron Rifkin, nor is he Richard Dreyfuss, though he is regularly mistaken for both. "There's not a shred of similarity between me and Richard Dreyfuss," Balaban says, "except we're both short and Jewish. And bald."

Balaban's latest movie is The Monuments Men, in which he plays Preston Savitz, a semi-fictional theatrical impresario and one of an unlikely band of middle-aged art experts squeezed into soldiers' uniforms and sent to Europe for the final act of the Second World War, to save what's left of the continent's cultural treasures from the Nazis. The film – based on a true story, and directed by George Clooney – boasts a cast list that only a star of Clooney's stature has the magnetism to attract: Damon, Murray, Blanchett, Goodman, Bonneville, Dujardin.

Yet for Balaban, such illustrious company is nothing new. In a career spanning some 70 movies, he has worked with Steven Spielberg, François Truffaut, Mike Nichols, Ken Russell, Orson Welles, Woody Allen, Robert Altman, Wes Anderson and Christopher Guest. And those are just the directors. Modest to a fault, he attributes his involvement in so many of the great films of the past four decades to simple mathematics. "I'm a character actor, so I can do five movies a year," he says. "If you're Brad Pitt, you can't do five movies in a year; you wouldn't be able to learn all the lines." (He has worked with Brad Pitt.)

Balaban's Gump-like screen résumé extends to television, where he had a crucial role in season four of Seinfeld, one of the great sitcom series arcs of all time. He played Phoebe's father in Friends and Hannah's shrink in Girls. He is indirectly responsible for the existence of Downton Abbey.

His literary credentials are not unimpressive: he wrote a highly-regarded behind-the-scenes account of the making of Close Encounters of the Third Kind, published a series of children's books about a bionic dog named McGrowl, and was once the subject of a Dave Eggers short story, "On Seeing Bob Balaban in Person Twice in One Week". Household name-fame may have eluded him, but Balaban wouldn't have it any other way. His advice to fellow actors was quoted by Rob Brydon, to Steve Coogan, in The Trip: "Bob Balaban said: 'Never be hot, always be warm'."

Balaban was born in August 1945, a day after the Japanese surrender, and brought up in Chicago, where his family owned a chain of cinemas. During his childhood, his uncle Barney was the president of Paramount Pictures, while his grandmother's second husband, Sam Katz, was the head of production at MGM, where he ran the studio's storied musical division.

"When I was 10, I went to California with my parents, and [Sam] took me to my first movie set," he recalls. "They were filming Meet Me in Las Vegas with Dan Dailey and Cyd Charisse. I had recently broken my arm, and Cyd Charisse signed my plastercast. To be on a giant movie set, in a pretend casino with 600 extras, fake trees, real cars – it was overwhelming."

Despite his industry connections, however, it didn't quite dawn on the young Bob that he could be in movies, so he went to study in New York, thinking he might have some luck on stage instead. In his junior year at NYU, he appeared in a hit off-Broadway production of You're a Good Man, Charlie Brown. In his senior year, 1969, he secured his first screen role in Midnight Cowboy, as a pitiful New York student who performs oral sex on Jon Voight. Shortly thereafter, Mike Nichols cast him in Catch-22 – also featuring Orson Welles – and, just like that, he was a jobbing film actor.

Balaban's next break came in 1977, when he not only played the translator for François Truffaut's character in Spielberg's Close Encounters, but also became the Frenchman's off-camera chaperone for the duration of the shoot. At the time, he had just returned to college to complete his degree. "I had to write a mammoth paper for a sociology course," he says, "so I did it on 'Social Stratification on a Film Set': it was a 100-page paper about the production of Close Encounters. I was at a party and happened to mention it to somebody, and they put it in a newspaper gossip column that I'd written 'a tell-all, behind-the-scenes diary of the biggest movie ever made'. The next day, I got calls from four separate publishers."

The subsequent book, Spielberg, Truffaut & Me: An Actor's Diary, sold over 200,000 copies. Given Balaban's privileged position on several similarly high-profile sets, it seems remarkable that he has never repeated the exercise. But, he says, "I wouldn't write an on-set book ever again. I don't want to be the actor you have to shut up in front of."

Rather, he aspired to step behind the camera, and so spent four months shadowing Sidney Lumet on Lumet's 1982 movie Deathtrap. Balaban has since directed a handful of features and several hours of TV. What lessons has he learnt from the greats? "All effective directors provide an atmosphere in which you can do good work," he replies. "Some do it by talking a lot, some by talking a little. Sidney Lumet believed in three-and-a-half weeks of rehearsal before each movie. He would do practice camera runs over and over again. Sydney Pollack, an equally wonderful director, once came upon me and another actor rehearsing our lines for a scene and said, 'I'd rather you practised it on film'. They had radically different ways of doing things, but they both made great movies."

For all his highbrow endeavours, Balaban does not consider himself an intellectual. "People mistake me for being far more deep than I am. I get cast as psychiatrists, doctors, lawyers. Even in You're a Good Man, Charlie Brown I was cast as Linus, the smartest seven-year-old boy in the world!"

In 1992, he was cast as the president of the NBC network in the celebrated fourth season of Seinfeld, for a plot arc in which Jerry and George produce a sitcom-within-the-sitcom. "The job description was: 'Elaine's going to fall in love with you. She's going to have her first orgasm with you. And then you're going to reject her'." At the time, Seinfeld was the biggest show on US television – and for once, nobody mistook him for Richard Dreyfuss. "I would be walking down the street in New York and tour buses would go by, full of people yelling, 'That's him! That's the guy!'."

Public recognition may have been a rarity for Balaban back then, but the rise of Netflix and its ilk has made him more ubiquitous than ever on people's screens, large and small. "Because I've been in about 800,000 movies, they're now on television the whole time, or streaming on Netflix, or you can download them from iTunes or Amazon and carry them around in your iPhone. Serious viewers see everything, so now character actors are much more familiar to people, and strangers will tell me they just watched something I made 25 years ago."

Though Robert Altman often receives the credit, it was Balaban who first discovered Julian Fellowes' talents as a screenwriter – or, as he puts it: "I unleashed the beast".

Sometime in the late 1990s, Balaban had the idea of developing a screen adaptation of an Anthony Trollope novel, The Eustace Diamonds, a family saga about a fortune-hunting woman and the battle for her late husband's estate. On the recommendation of a mutual friend, he enlisted Fellowes – then a small-time supporting actor and occasional TV writer – to pen a script. Fellowes, who composed the first draft for free, did a great job, Balaban says, though the film was never made.

"Two years later, I was sitting in my office in New York feeling desperate: I can't just keep being an actor, nobody is asking me to direct much, I've got to produce things, I need a project. Who do I know? Robert Altman. What am I reading right now? Agatha Christie. Wouldn't it be great if Robert Altman directed an Agatha Christie movie? So I went to [Altman] with the germ of an idea: a bunch of very fancy people on an estate in England in 1935. There's a murder, and they have to solve it by the end of the weekend."

As producer, Balaban persuaded Altman to direct the film, and suggested Fellowes write the script. Gosford Park was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture, losing out to the vastly inferior A Beautiful Mind. But Fellowes won the Oscar for Best Screenplay, and the rest is history. Balaban has not been invited to appear in Downton, Fellowes' monster TV hit, but the two remain close, and are presently at work on another, undisclosed film project.

In The Monuments Men, Balaban shares much of his screen time with Bill Murray; their characters are a kind of wartime Odd Couple, a two-man, US Dad's Army. The actors also worked together on Wes Anderson's last two films, Moonrise Kingdom and The Grand Budapest Hotel. "Some people, as you get to know them better, you think, 'I should have stopped at hello'. But the more you know Bill, the more interesting he gets," Balaban says.

"When we were filming in Berlin, he took me to a meeting of what seemed to be Buddhist monks: 200 people with their shoes off, praying in a foreign language. We were the only ones not wearing robes. A guy mixed a weird paste in a pot, which he spooned into our hands for us to eat. I was like, 'I can't eat this! I don't know where it came from! What if it's chopped goat faeces or something?!' So I walked around with it in my hand for an hour. But Bill just gulped the whole thing down in one. That's the difference between Bill and me."

I try to explain to Balaban the phenomenon of the 'Bill Murray Story' – that there are countless apocryphal accounts of Murray turning up unannounced to non-celebrity parties, softball matches, driving a golf buggy through Stockholm or randomly accosting members of the public and telling them, "No one will ever believe you". A lot of people have Bill Murray Stories, true or fictional. But I don't think Balaban quite grasps the concept. Our interview is part of a The Monuments Men press junket at the Four Seasons hotel in Beverly Hills – which means Clooney, Damon and co are doubtless being interviewed by other journalists in nearby suites. So it is fitting, if not wildly implausible, that minutes later we are interrupted by a knock at the door, which opens to reveal: Bill Murray.

Exactly as affable as you'd expect, and wearing a loud, Navajo-patterned shirt and truly excellent facial hair, Murray introduces himself, before asking Balaban which airline he thinks would be most agreeable for their imminent return trip to Berlin to publicise The Monuments Men and The Grand Budapest Hotel. (Balaban likes Air Berlin; Murray argues for Air France.) This must be what Balaban's whole life is like, I think to myself: punctuated by frequent phone calls or knocks at the door from movie stars and directors, each of them eager to discuss travel plans or their next project.

After a few minutes, Murray, who is 63, excuses himself to go and play basketball. "Bill is such a unique bird," Balaban says affectionately, once his friend has left. "He lives completely true to whatever is going on with him at any given moment. He's just following his muse all the time. It's very inspiring to be around. I'm not at all like that"

'The Monuments Men' is in cinemas from Friday

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments