Nicole Kidman in Photograph 51: Anger at 'slur' on Rosalind Franklin's colleague in new play about the DNA pioneers

‘Photograph 51’ gives Rosalind Franklin credit she is due – but the reputation of a colleague suffers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

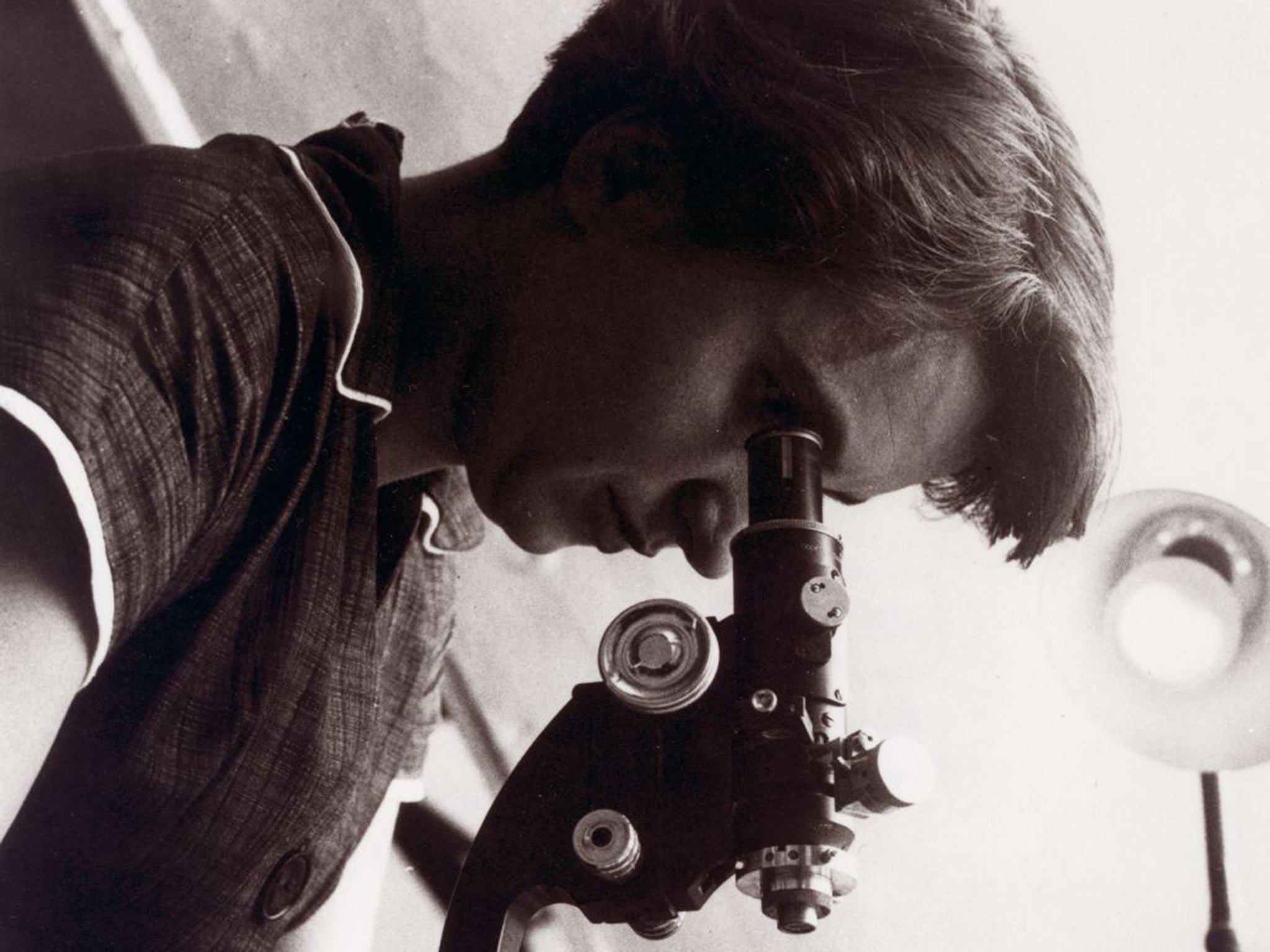

Your support makes all the difference.It was the most important breakthrough in 20th-century biology, and now the story of the DNA double helix is the subject of a West End play starring Nicole Kidman as Rosalind Franklin, a scientist cruelly denied a share in the Nobel Prize.

Photograph 51, at the Nöel Coward Theatre in London, emphasises the key role of Franklin. It portrays her as a woman tortured by institutional sexism and side-lined by her male contemporaries, especially her colleague at King’s College London, Maurice Wilkins, played by Stephen Campbell Moore.

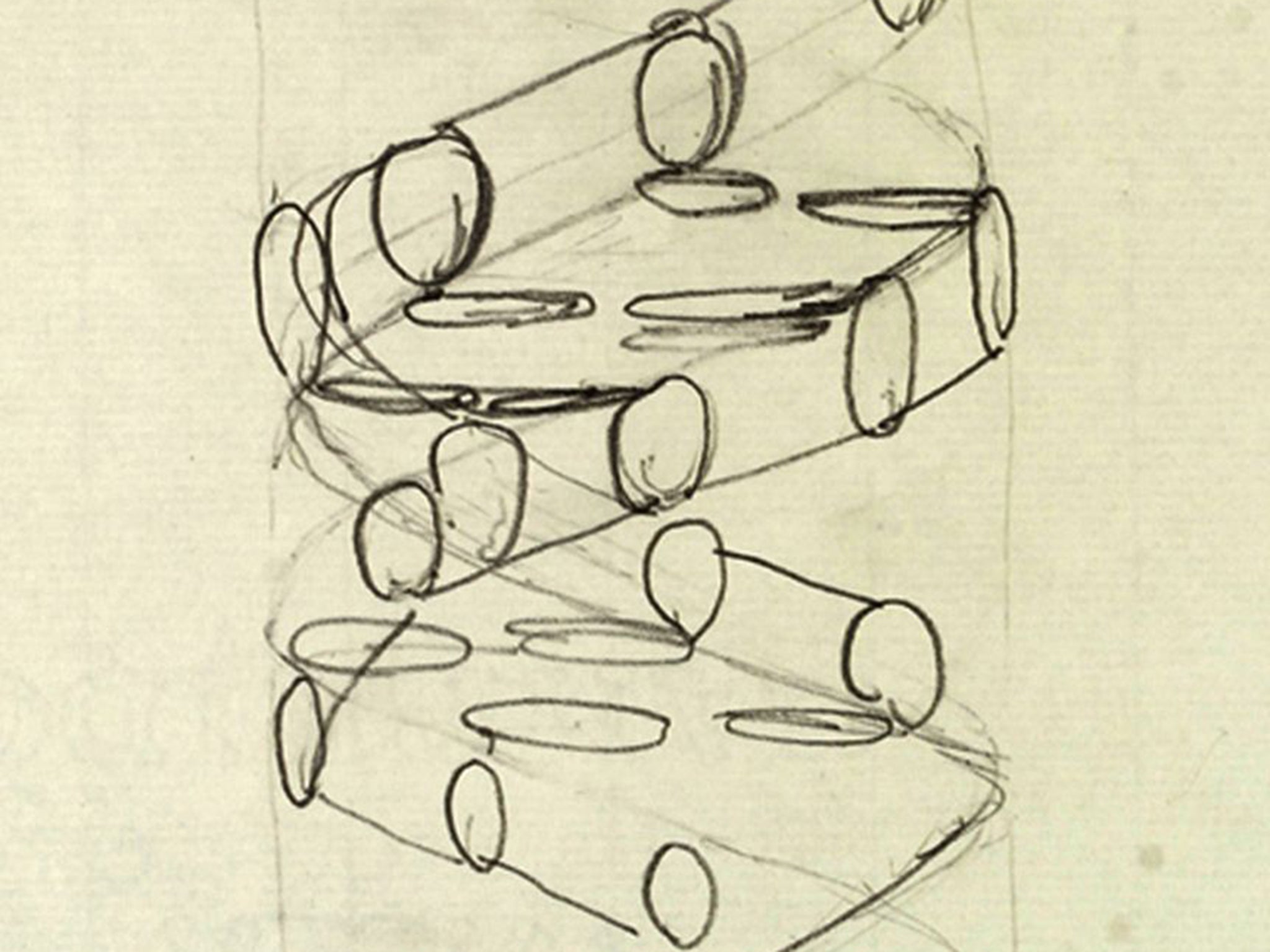

In one pivotal scene, Wilkins is shown taking Franklin’s seminal X-ray image – photograph 51 – from her desk drawer when she was not present and showing it to one of her competitors, giving the strong impression that Wilkins had in real life “stolen” her work.

For those who knew Wilkins, who died in 2004 aged 87, the fictionalised account by playwright Anna Ziegler and director Michael Grandage neither matches the facts nor what they remember of the man himself. For some of Wilkins’s contemporaries the slur on his reputation needs to be answered. They believe it was Wilkins, not Franklin, who provided the crucial experimental data that confirmed the DNA double helix that was postulated by Francis Crick and James Watson in Cambridge.

“I would say such behaviour would have been completely out of character. I have never doubted his honesty and integrity,” said Jim Torbet, whose PhD at King’s was supervised by Wilkins.

“I can’t imagine him searching through a desk that was not his own. But, like the author of the play, I wasn’t there. The man has suffered too many calumnies,” said Dr Torbet, who got to know Wilkins after the years between 1951 and 1953 covered in Photograph 51.

Two people who were at King’s at that time were Tony and Margaret North, who worked on the same X-ray diffraction method that led Wilkins and Franklin to the structure of DNA. They were both research students from 1951 to 1955, and married soon after their PhDs. Tony North, an emeritus professor at Leeds University, has spent a lifetime studying the structure of biomolecules using X-ray crystallography, the same technique used by Wilkins and Franklin to unravel the double helix. He and his wife recall the events quite clearly. “I shared X-ray equipment with Maurice and Rosalind. Margaret knew Rosalind quite well, often lunching with her and others in the [female only] ‘combination room’,” Professor North said.

Photograph 51 makes much of Franklin being excluded from the male-only senior common room at King’s, which Watson in his 1968 bestseller The Double Helix describes as an anachronism even by the sexist standards of the 1950s.

The play also portrays photograph 51 as being central to Watson and Crick’s theoretical model building. But it fails to make it clear that this photograph was taken by Wilkins’s PhD student, Ray Gosling, not Franklin. Neither does it make clear that, although photograph 51 was the clearest image at the time, it was just one of several produced by Gosling and Wilkins that had got Watson and Crick interested in DNA.

Professor North said that Wilkins had to know what Gosling was doing, as he rather than Franklin was his PhD supervisor. Franklin was ineligible for the role because she did not have a formal university position, but a personal research fellowship, Professor North said.

“The result is that Maurice had every right to know what Raymond had been doing and what results he had achieved, so that he had a right to see photo 51 without seeking Rosalind’s permission,” he said.

Brian Sutton, professor of molecular biophysics at King’s College, said: “The facts are clear. Maurice had a copy of photograph 51 in his possession, along with many records from Franklin, handed to him by Gosling. He showed it to Watson with the implication that it was with Franklin’s consent.” So was the play right to portray Wilkins as someone who rifled through Franklin’s drawer? “That absolutely didn’t happen. Wilkins didn’t ‘steal’ it or show anything that wasn’t his,” said Professor Sutton, who advised on the play.

As for the 1962 Nobel Prize shared between Crick, Watson and Wilkins, most of those familiar with the story agree it was fair. Franklin sadly died of cancer in 1958; the prize is never given posthumously, and can’t be shared by more than three people. It is true that Franklin’s role was unfairly underplayed by Watson’s 1968 account. But those who knew Wilkins believe it is also fair to protect his scientific and integrity.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments