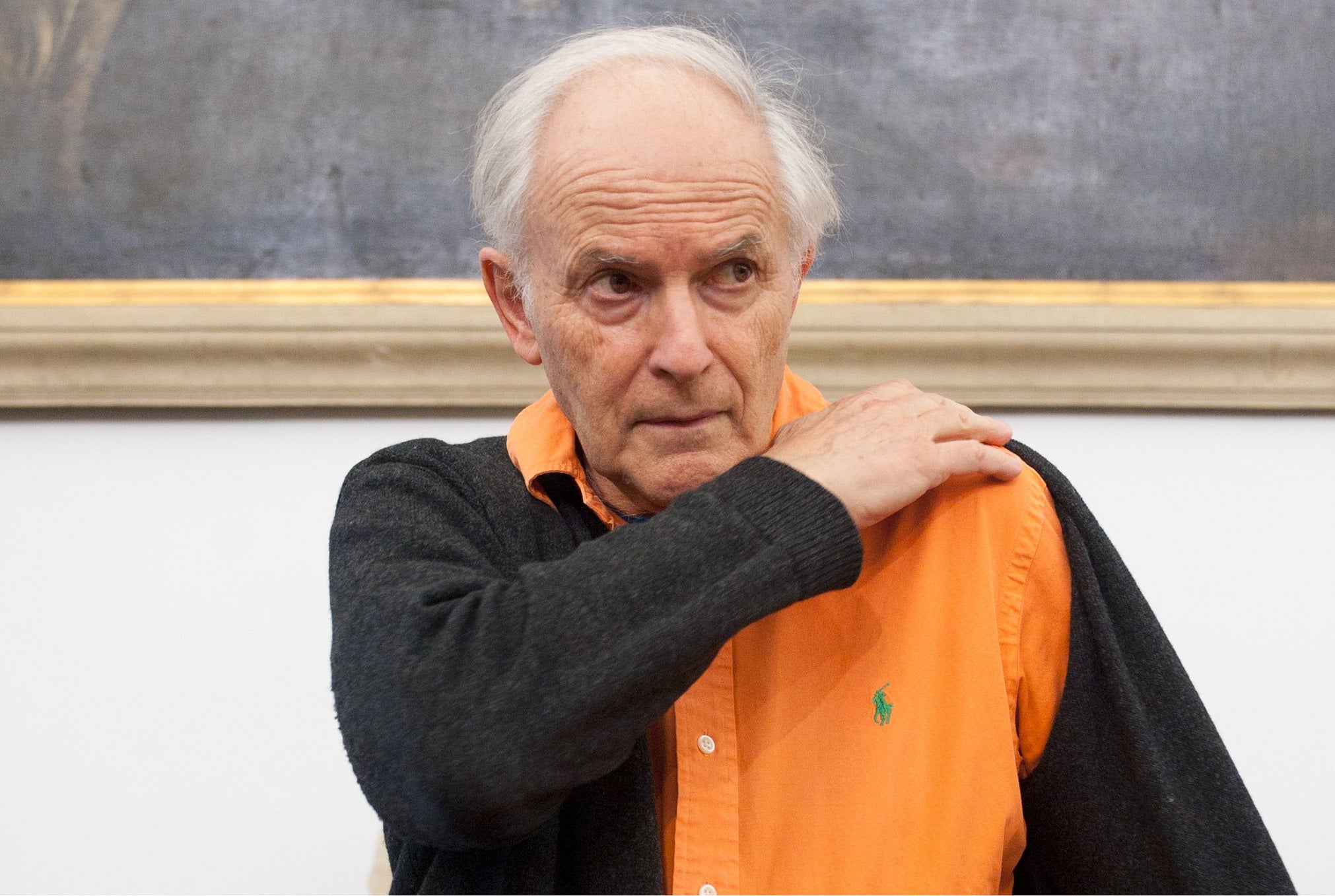

Obituary: Harry Kroto, Nobel Prize-winning chemist

His research opened up the possibilities of nanotechnology

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Harry Kroto, who shared the 1996 Nobel Prize in chemistry for his role in the discovery of the buckyball, a spherical carbon molecule that excited researchers around the world with its promise of advancing scientific understanding of a chemical building block of life, died 30 April near Lewes, England. He was 76.

Dr. Kroto was trained in spectroscopy, a field of science in which the spectrum of light from an object, such as a star, is studied to infer that object’s chemical composition. He was researching the carbon molecules in interstellar space when he initiated a fruitful collaboration with two American chemists at Rice University in Houston: Richard E. Smalley and Robert F. Curl Jr.

The three, who together would receive the Nobel, met with other colleagues at a high-powered Rice laboratory in 1985.

“This lab,” one collaborator, Jim Heath, told the journal Science, “is like being in an Army helicopter or something: You have five lasers going over your head; it’s noisy; all kinds of pumps are going and data coming on screen. But Harry, whenever he saw anything a little bit unusual, he would really key in on it.”

Over an intense period of days, Dr. Kroto and his collaborators conducted experiments that resulted in the discovery of a carbon molecule unlike graphite or diamonds, the only previously known forms of the substance.

The molecule they chanced upon contained 60 carbon atoms and was highly stable. When they assembled it in a model, the molecule revealed itself to be beautiful: It resembled the geodesic dome, such as the one at Epcot center at Walt Disney World, patented by the inventor R. Buckminster Fuller.

(To those unfamiliar with geodesic domes, the molecule might resemble a football.)

The scientists agreed to name the molecule buckminsterfullerene, or fullerene. In popular parlance, the molecules became known as buckyballs.

Besides the immediate advancement in pure science, the findings seemed to promise future applications in fields as varied as superconductivity and medicine. The study of buckyballs led to the discovery of cylindrical carbon structures called carbon nanotubes, which propelled the field of nanotechnology.

“From a theoretical viewpoint,” the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences declared in awarding the Nobel, “the discovery of the fullerenes has influenced our conception of such widely separated scientific problems as the galactic carbon cycle and classical aromaticity, a keystone of theoretical chemistry.”

Another love was music. He once told National Public Radio that he had thought of a career as a guitarist until “Eric Clapton came along and made me look like someone with honey stuck on their fingers.” Speaking to students as a Nobel laureate, he encouraged them to pursue endeavors in which they would never be satisfied with second-best.

The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments