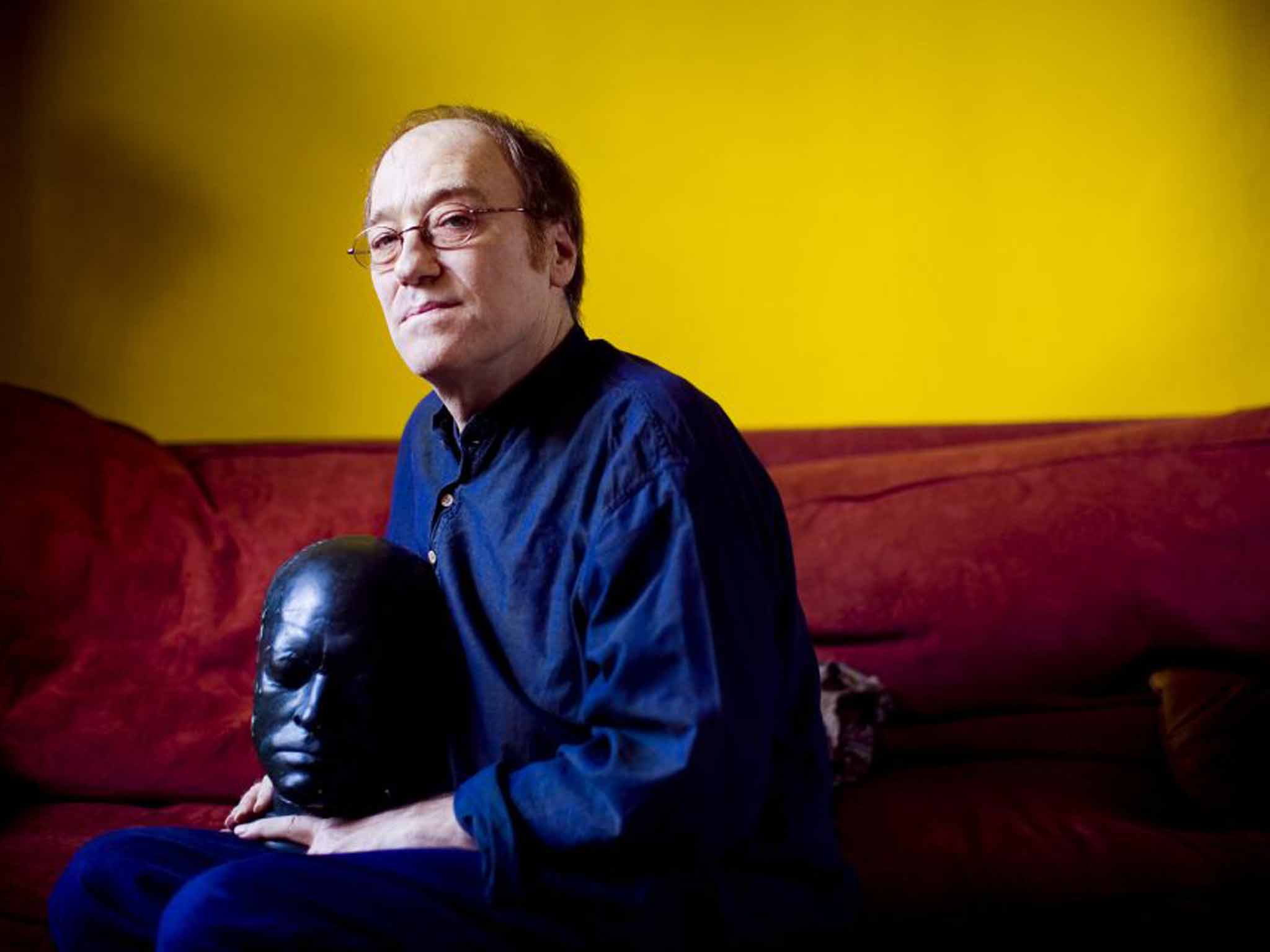

Mike Marqusee: Author and campaigner who fought to preserve Labour's socialist soul and wrote acclaimed books on Dylan and Ali

His sense of humour was immensely tickled by EW Swanton's verdict that "he writes well, if with a warped intelligence."

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Anyone who in the late 1980s picked up Slow Turn, a cricket novel by Mike Marqusee, was likely to be puzzled. It began with a vividly acute description of the mental pressures of facing top-class spin bowling that it seemed could only have been penned by somebody who had played at a very high level. Yet the Mike Marqusee known as the moving spirit of Labour Briefing, house journal of the party's "hard left", was an American.

There truly was only one Mike Marqusee. That passion for cricket was perhaps the unlikeliest, in terms of background, of many pursued by this polymathic self-described "deracinated American Marxist Jew". Once he conceived a passion – whether for cricket, quattrocento art, Bob Dylan, Star Trek, William Blake or most things to do with South Asia – it was pursued to a level at which his knowledge and insight impressed established experts. Diagnosed with multiple myeloma at 54, he acquired sufficient medical knowledge to, as he put it, "know when the doctors in House are bullshitting."

Much of this knowledge went into beautifully written, acutely argued books and articles. One of the innumerable reasons for regretting his death is that he was unable to complete a long-cherished project on Blake.

Those interests were examined through an exceptional intellect refined by childhood exposure to Talmudic logic and the rigour of the very best Marxists. It made him a formidable polemicist, but his lifelong socialism was never dry or narrow. A pluralist and internationalist by instinct and intellect, he was endlessly exasperated – and never more so than as a leading member in the early 2000s of the Socialist Alliance and the Stop The War campaign – by the endemic doctrinal and personal fissiparousness of the left. In person he was the absolute antithesis of the stereotypical joyless activist – warm, welcoming, generous and humorous, with a glorious sense of the ridiculous.

He was a "red diaper" baby. John and Janet Marqusee were Communists whose great enduring regret was a joint decision that John should give evidence to Senator Joseph McCarthy's red-baiting Un-American Activities Committee. It was predictable that the teenage Mike was enthused by the youth culture of the 1960s, the battle for civil rights and anti-Vietnam protests, less so that he also threw off the reflexive Zionism of his elders.

An academic high-flier, he was destined for Yale but in 1971 chose, impelled by a love of Shakespeare, to come to Britain to read English at Sussex University. America's loss was Britain's gain, although neither perhaps ever fully appreciated it.

A youth worker in London, he was drawn back into politics by the impact of Thatcherism in 1979, becoming a significant polemicist in Labour's left-right battles of the 1980s. He also met his lifetime partner Liz Davies, a lawyer. Like all political couples he and Liz, who survives him, sometimes disagreed.

He left the Labour Party before she did, disenchanted not least by events in 1995 when Liz, an Islington councillor, was unfrocked as parliamentary candidate for Leeds North East by a New Labour apparatus determined both to look tough on left-wingers and to settle London-rooted scores. This gave her a profile whose dubious reward was two years' membership of Labour's National Executive Committee. But their mutual support never wavered.

By then he had made his own name as a writer. Defeat from the Jaws of Victory (1992), a sharply revisionist view of Neil Kinnock's Labour Party written with the academic Richard Heffernan, was followed by Anyone But England (1994), a cultural and historical analysis of English cricket which was hailed with delight by radicals and wary respect by conservatives. His sense of humour was immensely tickled by EW Swanton's verdict that "he writes well, if with a warped intelligence."

Then came War Minus The Shooting (1996), a travelogue around the 1996 Cricket World Cup which combined cricket with sharply observed analysis of the South Asian host nations and gave him lasting minor celebrity in India. There were no more cricket books, but plenty of columns and articles. Instead he pursued towering figures from his childhood, examining Muhammad Ali in Redemption Song (1999) and Bob Dylan in Chimes of Freedom (2003). Redemption Song was shortlisted for the William Hill Sports Book of the Year award, but was unlucky to coincide with another outstanding study of Ali.

His writing was always personal, but never to the extent that – as with some highly personal writers – the larger picture is obscured. There were hints of the great autobiography he never got to write in If I Am Not For Myself: Journey of an Anti-Zionist Jew (2008) with its mix of family history and analysis of Jewish culture and politics.

By then he had been diagnosed with cancer. Given four years to live, he survived for nearly twice as long. While he ridiculed the stereotype of the brave cancer patient, there was genuine courage in the clear-eyed manner with which he confronted his own illness.

The treatment was brutally debilitating but he continued to write, mixing personal reflections with forensic examination of the state of the modern NHS. A book of poems, Street Music (2012), which opened with "Multiple Myeloma: A Suite", was followed last year by The Price of Experience: Writings on Living with Cancer. Mike Marqusee was a life-giver – a principled, warm, funny, astonishingly smart man driven by a passionate concern for justice. In his own native argot, this was a mensch. µ HUW RICHARDS

Michael John Marqusee, writer and political activist: born New York 27 January 1953; partner to Liz Davies 1990-; died London 13 January 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments