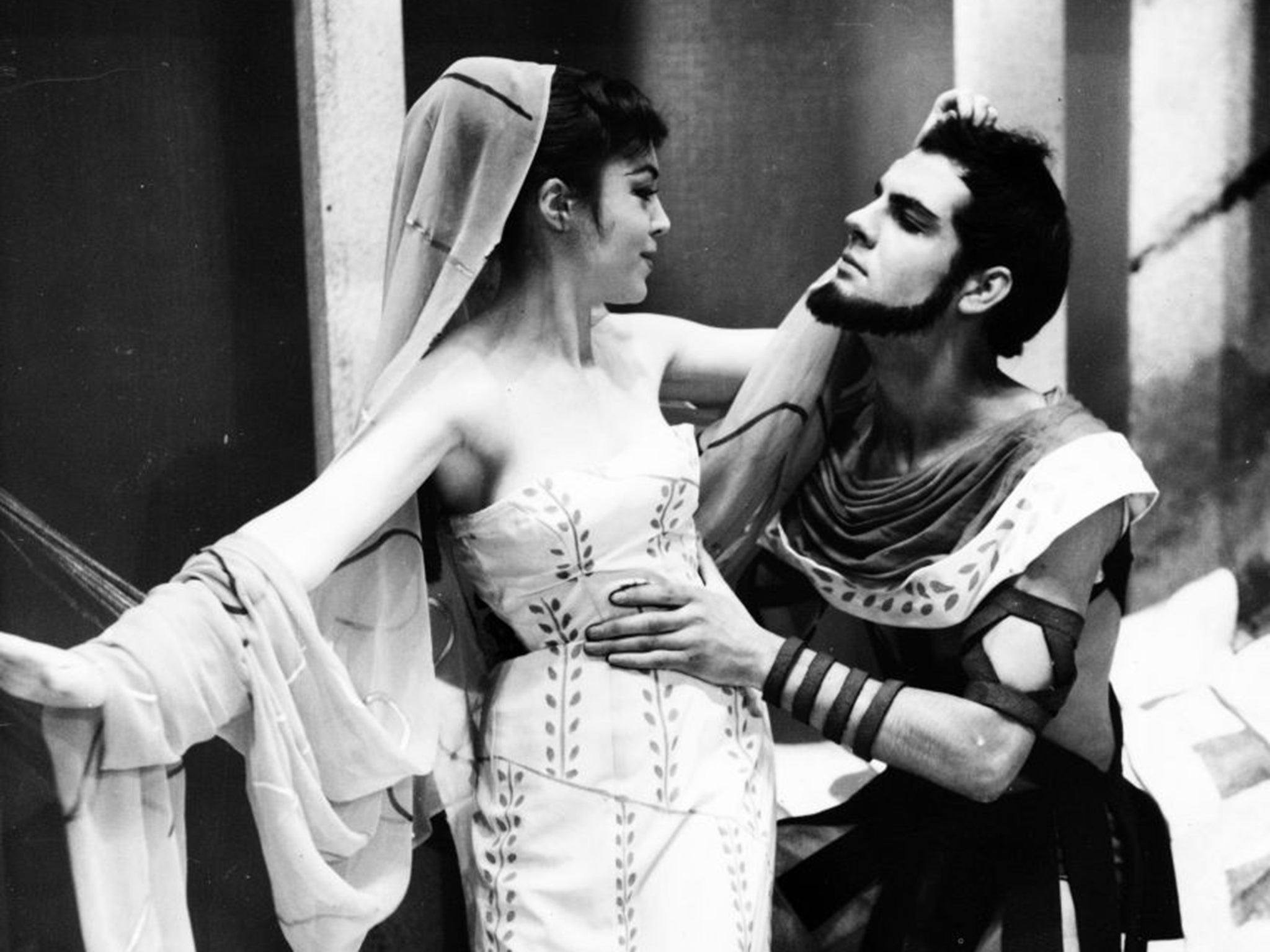

Natasha Parry: Actress hailed for her grace and control who forged a solo career while also working with husband Peter Brook

Parry made her screen debut at the age of 19, and throughout the 1950s her dark beauty and modest nobility lent itself well to monochrome delights

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The statuesque beauty of the actress Natasha Parry was the perfect vehicle for the grace and control she brought to a wealth of stage triumphs, in an unpredictable career that was never a straight line, but rather was wondrously interwoven with her love for her husband, the great director Peter Brook. Their romance lasted 70 years: it delivered pioneering work from both of them, and one of the most exciting partnerships in theatrical history.

Parry made her screen debut at the age of 19, and throughout the 1950s her dark beauty and modest nobility lent itself well to monochrome delights such as the delicious Gothic noir melodrama Crow Hollow (1952), Ealing Studios’ unusually female-focused Dance Hall (1950) and the thriller Midnight Lace (1960). But while fellow starlets such as Jean Simmonds and Deborah Kerr found fame in Hollywood, Parry, blessed with a perfectionism of which even her husband was in awe, would achieve her greatest glories on stage.

The stepdaughter of second-feature director Gordon Parry, she was born in London in 1930 and had already been acting for three years when, at the age of 15, she met Brook during the interval of a ballet matinee at Covent Garden. He was instantly captivated; perhaps it was partly the sense of express and vivacity in her name that chimed with his boyhood devotion to the character Natasha in War and Peace.

After a brief courtship ended he tracked her down in France, but she rejected him. He trudged the city, haunted by “the heroine of my Paris adventure”. Then in 1950 she sent him a telegram. They met again in Oxford, married in secret a year later and remained together for the rest of her life.

They first worked together when she played Cordelia to Orson Welles’ King Lear for US television in 1953. She was already building a reputation on the stage: And The Wheel Turns (1950) was an interesting triptych in which three couples are blighted by a malevolent stranger who forces them to question their relationships, and the following year there were successes with Figure of Fun at the Aldwych, and at the Embassy, A Matter of Fact, an exploration of capital punishment. She contracted TB in 1952 and had to take a year off but made an emphatic return alongside John Mills and Gwen Ffrangcon Davies in John Gielgud’s hugely successful staging of Charley’s Aunt, then considered the play’s finest production to date.

She joined the Meadow Players at the Oxford Playhouse for a run of West End transfers, including Lysistrata (1958) and a Molière double bill in which she, Pauline Yates and Delena Kidd “spoke with scintillating éclat”, as one critic put it, as the three protagonists of The School for Wives Criticised. After playing Miranda in Dryden and Purcell’s musical reimagining of The Tempest at the Old Vic in 1959 she was directed by her husband again as Rex Harrison’s leading lady in a Broadway production of Anouilh’s The Fighting Cock in 1960, and was a loving Queen to Alec Guinness in Ionesco’s Exit the King (Edinburgh Lyceum, 1963).

In Paris, Brook set up the International Centre for Theatre Research in 1971, and Parry became a key figure as they took shows to the Middle East and Africa, most notably Orghast, in which 20 actors from 10 nations acted out man’s inhumanity to man in front of the cliff tombs of the Persian Kings, at the finale optimistically leading the audience towards the rising sun.

Back in Britain, Parry excelled first on the London fringe in Secrets (Bush, 1974), then as Blanche Dubois in A Streetcar Named Desire (Liverpool Playhouse, 1975). She stayed with Williams for a Parisian production of Night of the Iguana at Brook’s Bouffes du Nord, then joined the RSC, first as Phaedra in David Rudkin’s acclaimed version of Hippolytus in 1978, then as the amorous widow of Gorky’s Children of the Sun (Aldwych, 1979).

She was commanding in Brook’s stark production of The Cherry Orchard in Paris in 1981, and in an English language version at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 1988 she was Clytemnestra in an intense Electra (The Pit, 1989). She acted with her daughter Irina in Brian Cox’s production of Mrs Warren’s Profession at the Orange Tree, Richmond in 1989.

She was typically meticulous as Gertrude to Adrian Lester’s Hamlet at the Young Vic in 2001: it was her last appearance on the stage, although perhaps her most celebrated was as Winnie in Brook’s mellifluous French language production of Beckett’s Happy Days at the Riverside Studios in 1997.

She came to television early, appearing as 40 different characters across six episodes in JB Priestley’s first piece for the medium, You Know What People Are (1955). She made a huge impression opposite a masked Anthony Quayle in the multi-award-winning The Rose Affair (1961), was poignant as the dying countess in Trevor Griffiths’ Occupations (1974), and the same year the truthfulness she strove hardest for worked wonders in Kingsley Amis’s doomy ghost story The Ferryman.

Her later film appearances included Lady Capulet in Zeffirelli’s modish Romeo and Juliet (1968), Oh! What A Lovely War (1969) and Brook’s Meetings with Remarkable Men (1979).

After a spell as an actress, Irina is now head of the National Drama Centre in Nice, while Parry’s son Simon is a film-maker. When she married Peter Brook, they both vowed never to “settle down”. Instead they went on boundless adventures together and took theatre into new realms, both geographically and artistically.

Natasha Parry, actress: born London 2 December 1930; married 1951 Peter Brook (one daughter, one son); died La Baule, Brittany 22 July 2015

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments