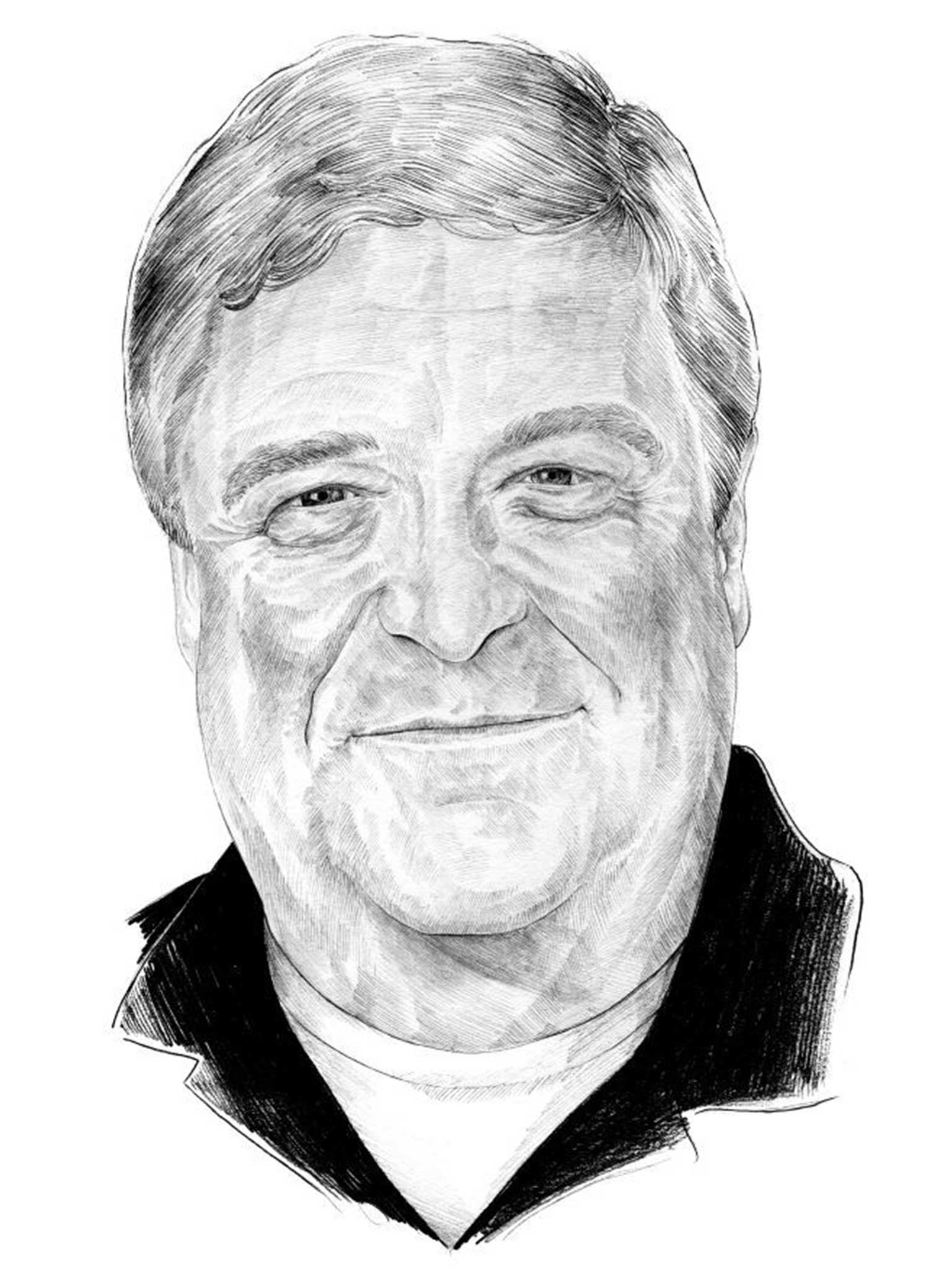

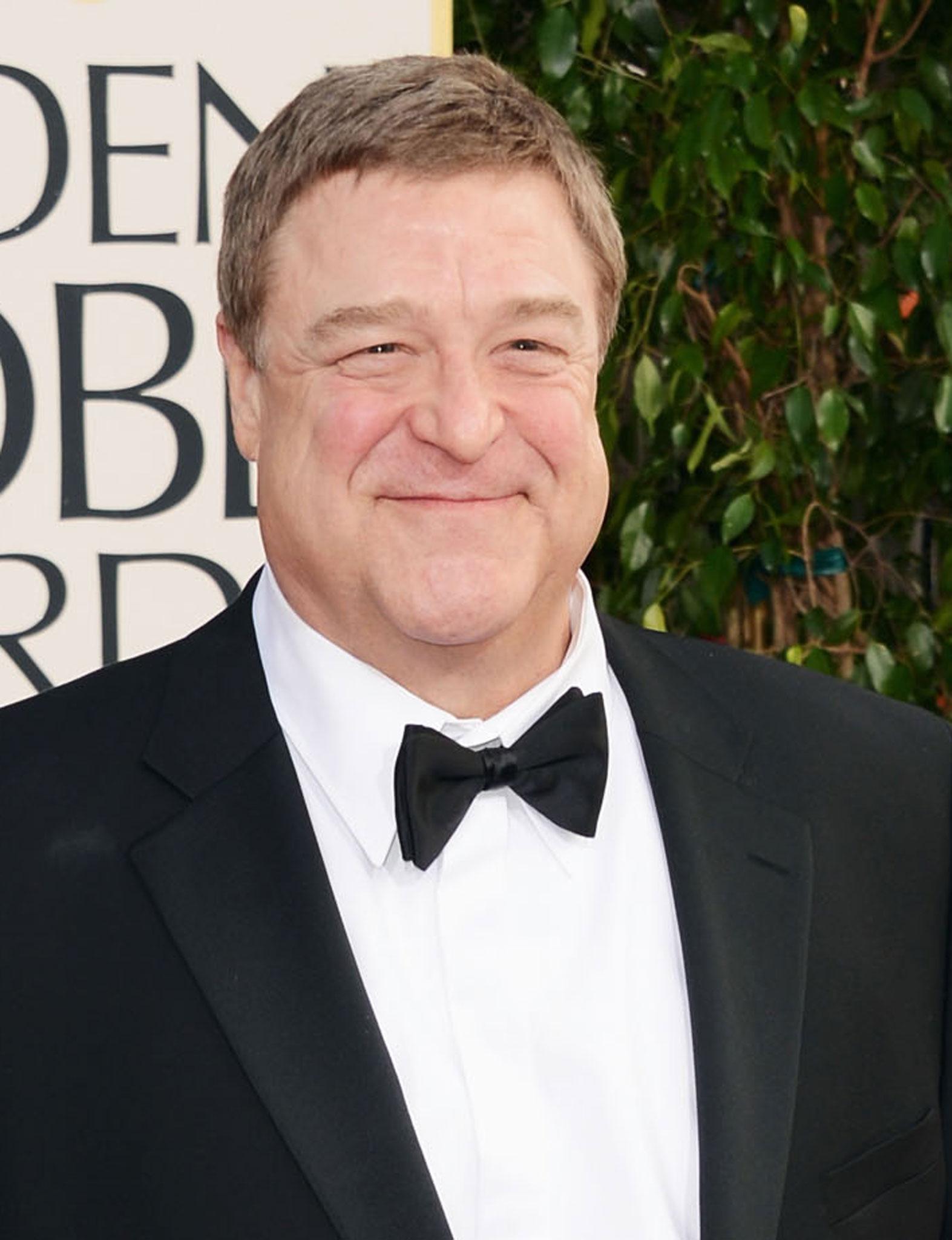

John Goodman: The big star with a small mouth lands in London for 'American Buffalo'

The ex-alcoholic and Coen brothers darling heads to London as one of the finest actors of his generation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.He is one of American cinema’s most ebullient and best-loved character actors, a big man with a big presence and a big voice. Now John Goodman is appearing on the London stage for the first time in a new West End production of David Mamet’s classic 1975 play American Buffalo. Fans will not find his character too much of a departure: the 62-year-old actor, who stars alongside Damian Lewis and Tom Sturridge, has earned a reputation as one of Hollywood’s most expressive cursers, and as Don, a small-time hustler, he gets plenty more practice in that.

One might expect Goodman to be trumpeting his presence in the play, putting the beef into buffalo and letting the UK know just how lucky we are to have an actor of his magnitude in one of our theatres. Instead, Goodman has been trying to convince the British press that he is “shy”, “inarticulate”, and that, in spite of all his magnificent comic performances in Coen brothers movies over the years, he “lacks the testicular fortitude” for stand-up comedy. He makes it seem that appearing in front of a live audience in any guise at all, let alone in a Mamet play, is “utterly terrifying”.

All this self-deprecation comes as a surprise. After all, on screen, Goodman is typically a formidable presence, and sometimes an intimidating one. In Rupert Wyatt’s recent film The Gambler, in which he plays a loan shark dispensing wisdom to Mark Wahlberg’s hapless gambler, he is shown holding court in a bathhouse. Balding, blubbery, with towels draped over him and sweat oozing from his pores, he looks like a gigantic jellyfish. It is a typical Goodman performance, avuncular and threatening by turns.

Goodman has always done his share of mainstream films and TV. For almost a decade, from 1988 until 1997, he was the blue-collar husband and father in the hugely popular sitcom Roseanne. He was the voice of the furry blue monster Sulley in Pixar’s Monsters, Inc and of Baloo in The Jungle Book 2. Directors have long looked to him to play the kind of down-to-earth family man who may have a bit of a temper, but whose essential decency is never in doubt.

That bonhomie is deceptive, though. What the Coen brothers have tapped into most effectively in Goodman is the darker part of his personality. It is hard to think of any screen character in recent years as obnoxious as the jazz musician Roland Turner he played in the Coens’ Inside Llewyn Davis (2013), a dried-up, heroin-addicted old misanthrope. It was the coldness and detachment of the character that so startled. It takes a moment or two to accept Goodman as someone so frankly repellent.

The legacy of a more lovable role, his portrayal of Vietnam veteran Walter Sobchak in The Big Lebowski (1998) lingers – but Goodman’s tantrums in that film don’t seem entirely feigned, either. Nor did he seem miscast as the ruthless movie mogul Al Zimmer in The Artist (2011), casually discarding and destroying silent era star Valentin (Jean Dujardin) as he goes searching for fresh meat.

There are plenty of demons in Goodman’s past. He has talked very openly about his alcoholism. “I couldn’t control it. Lying to my wife all the time about how much I drank is where I’ve been. Hiding something all the time. Drinking at work,” Goodman, who has been sober since 2007, told Vanity Fair in an interview last year. He is also open about his size – “I wish I wasn’t so fat” was the headline of another recent interview.

A cod psychological interpretation of his career would suggest that he has benefited professionally from these anxieties in his private life. The best character actors tend to have complicated and mercurial personalities. Look at Alec Guinness, who, like Goodman, had an affinity for playing seedy or downright evil characters as well as the genial everyman types.

Yet it can’t be said that Goodman’s career has been derailed by any struggles off screen. He is an astonishingly prolific actor, on both small and silver screen. His most recent success came as the brash Republican senator from North Carolina in Garry Trudeau’s political satire Alpha House, a TV series made by Amazon.

Credits stretch from Stephen Poliakoff dramas (the BBC’s Dancing on the Edge) to big-budget studio blockbusters. He has played cavemen (The Flintstones) and monarchs (King Ralph). Many of his movies (The Artist and Argo among them) have been Oscar winners. Few can match such range.

In his last appearance on stage, in 2009, Goodman appeared as Pozzo in a production of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, dressed like a British country squire and adopting a booming upper-class English accent.

Born in St Louis, Missouri, in 1952, Goodman grew up in humble surroundings. “He’s a Midwestern boy who comes from a place where accepting praise and accolades is physically painful and even the hint of confidence in one’s talents is sin No 1,” his friend Tom Arnold said of him in The New York Times.

Goodman was only two years old when his postman father died of a heart attack. As a youngster in Missouri, he was a promising American football player who won a sporting scholarship to Missouri State University. It was there he discovered drama. (One of his classmates was Kathleen Turner, the future star of Body Heat.) Eventually, in the mid-1970s, he headed to New York and tried to make it as an actor. There were the usual setbacks – the waiting and bartending jobs, the bit parts and the roles in commercials – but by the mid-1980s, the film roles had started coming.

One of his strangest early parts was as a country-and-western singing “clean room technician” in David Byrne’s arty and experimental comedy True Stories. He also registered strongly as the fulminating Coach Harris (“You just got your asses whipped by a bunch of goddamn nerds!”) in crass teen comedy Revenge of the Nerds (1984).

.jpg)

Then he landed a role in the Coen brothers’ Raising Arizona (1987) – and the most fruitful relationship of his career began. “They started writing these characters specifically for me,” Goodman recalled to one interviewer. “They seemed to see in me something I could bring to those characters. God only knows what it is. I don’t want to know! Mostly I think it’s just a fat guy who’s really loud.”

Goodman recently told Rolling Stone magazine that his role as Charlie Meadows in Barton Fink (1991) is his favourite among the Coens’ filmography. “He was very sympathetic – for a man who was a snake, that is. He was someone I could sink my teeth into. Homicidal maniac, but kind of a nice guy.”

It’s a revealing quote, one that hints at what makes Goodman so special as an actor. He can take the most hard-bitten and psychopathic villain and get an audience on his side. At the same time, he is able to hint at the seething doubts and insecurities of seemingly well-adjusted, contented types.

Of course, the largeness and the loudness help – along with that Fatty Arbuckle-like instinct for comedy. Perhaps we should take claims about his crippling shyness with a pinch of salt. He has been dubbed America’s “scene stealer” – not a reputation you can pull off if you’re hiding in the background.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments