Joanna Dunham: Actress best known for playing Mary Magdalen who could depict the innocent or the murderess with equal facility

While at Rada she became friends with the future Beatles manager Brian Epstein

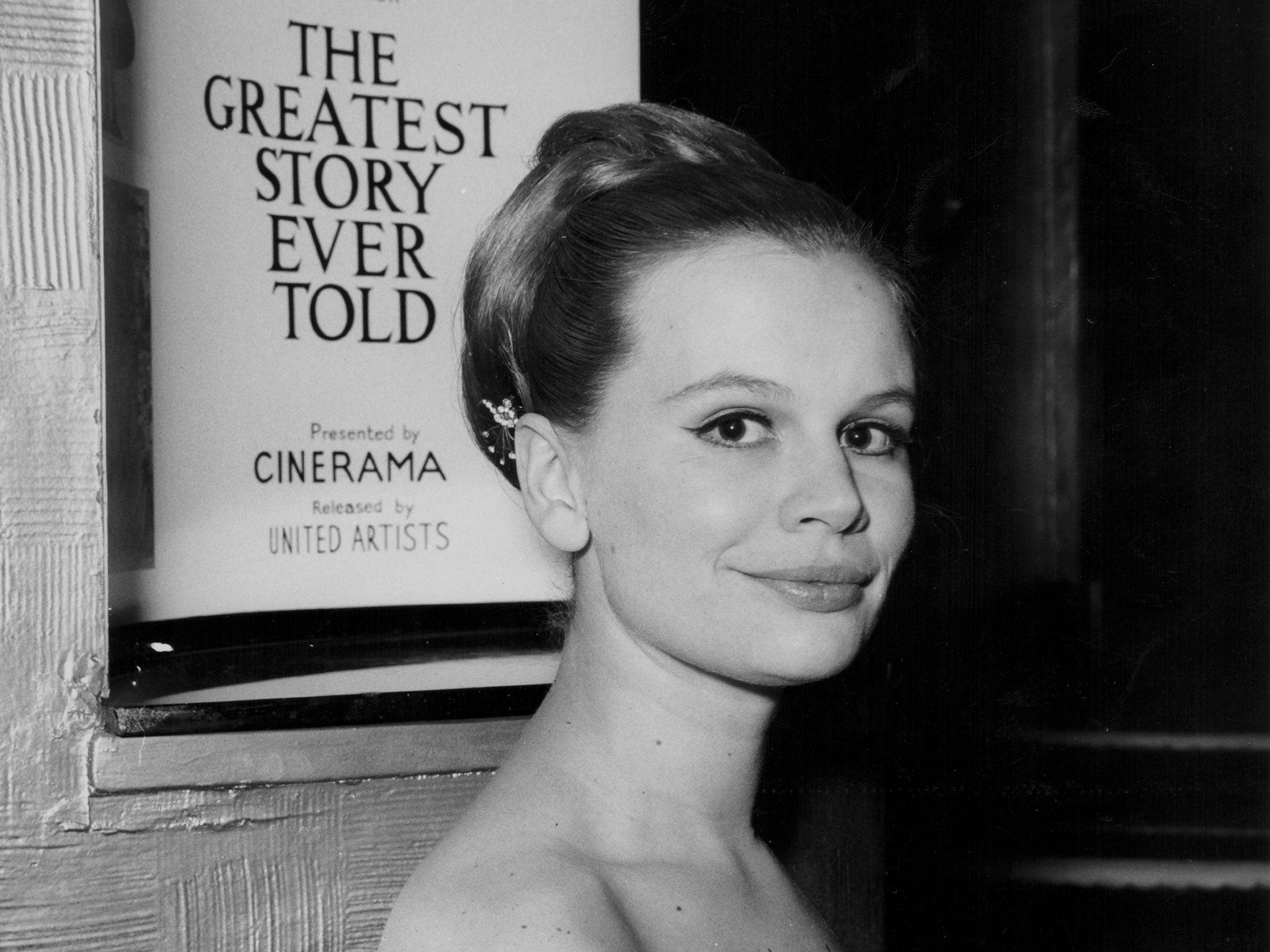

The beguiling Joanna Dunham never quite became a star, but none the less carved out a solid career on stage and screen which inexplicably petered out somewhat in later years. Her break came playing Juliet for Franco Zeffirelli with the Old Vic in 1962; when the production toured New York she was spotted by Marilyn Monroe, who recommended her to George Stevens for the part of Mary Magdalen in The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965).

But first and foremost she was a television player, and a fine one; her mix of summertime looks and dark eyes worked wonders on the small screen. She could be “the lovely, innocently vulnerable Joanna Dunham”, in one critic’s words, but she was also marvellous at playing wrong'uns; duplicitous lovers, murderesses and manipulators were a speciality, whether in classical theatre or television thrillers.

She was born in Luton in 1936. Her father – from whom she inherited a gift for painting – was an architect, as was her first husband. She was educated at Bedales in Hampshire, and then, on scholarships, studied at the Slade School of Art (where she was taught by Lucien Freud), and at Rada, where she befriended fellow student and future Beatles manager Brian Epstein. Fresh out of drama school, she drew attention for a striking performance as Vera in Turgenev’s A Month in the Country at the Tower Theatre, Canonbury in 1958.

The same year, she made her professional stage debut under future Royal Court Artistic Director Oscar Lewenstein in The Deserters at Liverpool Playhouse, and her television debut, as a “proud and fiery” soubrette in Shaw’s Arms and the Man. From then on she juggled the two mediums skilfully; her classical roles were often meaty because of her fluency as a verse speaker, something that as early as 1961 won her the opportunity to read Helena’s passages to Hermia from A Midsummer Night’s Dream at Southwark Cathedral at that year’s Shakespeare Memorial Service.

Her aforementioned Juliet took her around the world, and on to the big screen, but the year-long filming of The Greatest Story Ever Told caused a headache when she became pregnant midway through. Stevens had no choice but to use contrived camera angles in later scenes, although he rose to the challenge in good spirits, remarking that “that Mary Magdalene always was trouble”.

Her film career never came to much, but the 1970s were her busiest decade on stage and television. At the Oxford Playhouse in 1971 she was the sensual wife in Sartre’s In Camera; the following year at the Hampstead Theatre she and Polly Adams were directed by Snoo Wilson in a lesbian drama, Bodyworks. Also in that Oxford season she was a vivid Desdemona in Othello.

Later stage triumphs included Blessed Memory, a one-woman piece by the Icelandic playwright Ornolfur Arnason at the Three Horses in Hampstead in 1980, as a woman looking back with regret on the wrong decisions she made in life: “Joanna Dunham speaks it all beautifully, never overdoing the cry for understanding inherent but not articulated in her character”, and Regan in King Lear at the Young Vic in 1980. Her Hermione in The Winter’s Tale there the following year was “charming, graceful and touchingly down to earth”.

In Ayckbourn’s Relatively Speaking at the New Vic in 1994 she gave a performance of “Celia Johnson quality, moving with subtle ease from naivety to archness”. Her last stage role was in a play by Guy de Maupassant, Taking Liberties, which had not been seen for 100 years until she and her second husband, Reggie Oliver, unearthed it. Oliver translated it and the couple staged it at Ipswich in 1995. It was described as “an excellent find, a French kitten of a play”.

The television play The Problem of Girlfriends (1960), set in a block of flats where three proves to be a crowd in an unexpected sense, was one of many Dunham performances for director Joan Kemp-Welch, the most significant being the now forgotten series Sanctuary (1967), which aimed to be “documentary fiction in the manner of Z Cars”, only about nuns not rather than police officers. Unlikely as it may sound, it was a thoughtful and deservedly well-received experiment.

Her best television role, however, was in Gavin Millar’s Play for Today filming of William Sansom’s eerie novel Goodbye in 1975. The story of a snoozy stockbroker whose world is overturned when his wife abruptly announces she is leaving him was expertly played by Dunham and Jeremy Kemp – Dunham “fair, cool and remote”, at times quite chilling in her handling of a woman for whom a love that may only ever have been a convenience has now fatally shrivelled to mere indifference.

In later years, moving back to her childhood home of Suffolk, she concentrated on painting, and in tribute to her mother held regular exhibitions in aid of the Alzheimer’s Research Trust. She leaves behind some fine work on canvas and on camera, the latter most often evoking that review of her first professional appearance: “proud and fiery”.

Joanna Elizabeth Dunham, actress and artist: born Luton 6 May 1936; married 1961 Henry Osborne (marriage dissolved; one daughter, one son), 1992 Reggie Oliver; died Saxmundham, Suffolk 25 November 2014.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies