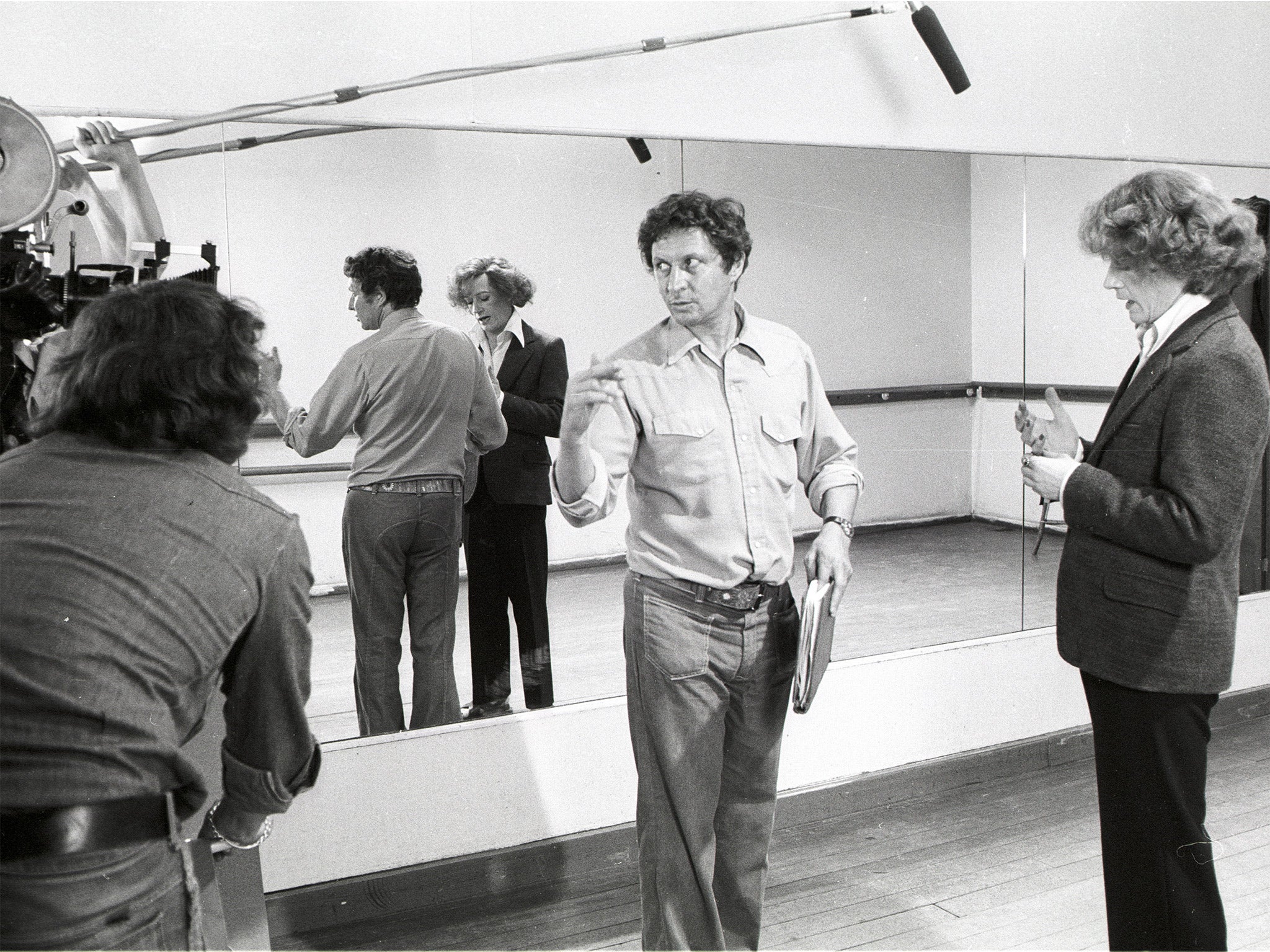

Jack Gold: Bafta-winning director of confrontational documentaries and touching dramas, including Goodnight Mister Tom

Gold was a steadfast storyteller who put people centre stage

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Jack Gold belonged to the finest generation of television directors we shall ever see. A quiet, humane man, at his best producing quiet, humane films, Gold was a steadfast storyteller who put people centre stage: not for him the scale and sweep of the epic. It was exactly this devotion to intimacy and humanity that made television the perfect medium for him and for the majority of his contemporaries, many of whom found when venturing into cinema that the voice, character and artfulness of their films would be significantly diminished.

Jack Gold was born on 28 June 1930, and studied economics and law at University College, London. He joined the BBC in 1954 as an assistant studio manager in radio, then crossed to television to become a trainee assistant film editor, learning his craft on schools programmes.

But heady times were dawning in television, and in 1960 he joined Donald Baverstock's Tonight programme, an early-evening mixture of studio interviews and filmed reports fronted by a stalwart brigade including Fyfe Robertson and Alan Whicker. Gold quickly became one of the staff directors on the show, producing up to five short films a week and ultimately nearly 400 shorts and 30 documentaries in just six years.

Happily, the pressure he was under meant that there was very little time for interference from above; indeed, it says a great deal about the opportunities for experimentation and for bold personal statements, even in early-evening television at that time, that it was one of these short films which gave Gold his break. A Tonight special about fox-hunting, Death in the Morning (1964), was an example of the kind of pioneering excellence that won television its spurs (and won Gold an SFTA, the forerunner to the Baftas).

It was a magnificent, confrontational piece, with Whicker following the Quorn Hunt through the Leicestershire countryside. It derived its enormous emotional impact (which surely mobilised the burgeoning anti-fox-hunting movement) from Gold's presentation of the hunt itself. His ability to make the audience feel the savage pursuit from the point of view of the victim was a vivid expression of both his humanistic concerns and his empathetic skills.

He had already made his first foray into drama five years earlier, having written and directed the upsetting experimental short The Visit (1959), which depicted the empty existence of an ageing spinster, exacerbated rather than alleviated by a visit from a jaunty, loved-up young couple. It is an impressively stark piece in which almost nothing happens, but in distressingly painstaking detail – a ghost of haunting films to come, such as Mike Leigh's Bleak Moments (1971) and the minimal later films of Alan Clarke.

When Tonight spawned a spin-off documentary series, Call the Gun Expert (1964), profiling the cases of Robert Churchill, a gunsmith who assisted police in gathering forensic evidence, Gold broke new ground by incorporating dramatic reconstructions into the programmes.

Ladies and Gentlemen, It Is My Pleasure (1965) memorably followed Malcolm Muggeridge on an American lecture tour, while later documentaries included the impressionistic Wall Street (1966) and Ninety Days (1966), a docudrama reconstruction of the interrogation of South African anti-apartheid activist Ruth First, in which, fascinatingly, First played herself.

It was no surprise that his debut film for The Wednesday Play remains a high-water mark for radical television drama. Jim Allen's The Lump (1967) was a furious, mud-splattered indictment of the lot of casual labourers in the building trade, starring Leslie Sands; like many of his contemporaries, including John Mackenzie and Herbert Wise, Gold had a remarkable knack for casting and for lifting truthful and undemonstrative performances from his actors.

He moved swiftly into cinema with the army drama The Bofors Gun (1968), and was on good form with the big-screen version of Peter Nichols' The National Health (1973), and with the wild-card in his pack, the supernatural thriller The Medusa Touch (1978).

Gold continued to work in television all the while, where he consistently produced interesting and distinctive work. From the final season of The Wednesday Play came the commendably restrained film Mad Jack (1970), Tom Clarke's dignified depiction of Siegfried Sassoon's pacifistic protesting. Also from Clarke came the equally celebrated and Bafta-winning Stocker's Copper (1972), again a historical piece in a contemporary strand (Play for Today) and again with an obvious relevance – this time dramatising a clash between police and Cornish clay miners in 1913, and mirroring the mood of a country only months away from the three-day week.

People always came before politics for Gold, even when dealing with contentious subject matter. His strangely neglected version of Hardy's The Return of the Native (1994), starring Clive Owen and Catherine Zeta-Jones, was typically unfussy and sympathetic, but even more neglected was Good and Bad at Games (1983), a story of public-school bullies becoming the target for revenge in adulthood, written by the novelist William Boyd. It was one of three excellent films Gold made for the new and deeply committed Channel 4 that year, the others being the thriller Praying Mantis, and Charles Wood's typically unclassifiable Red Monarch.

At ITV, Gold made two films which show no signs of ever ageing: The Naked Civil Servant (1975), the delightfully brazen but touching biopic of Quentin Crisp, and the weepy wartime fable Goodnight Mister Tom (1998), one of a number of collaborations with his friend John Thaw. Gold also directed Thaw's final outing as Inspector Morse in 2000 and episodes of the legal drama Kavanagh QC (1997-2001).

Winner of two Emmys, a Golden Globe, three Baftas, two Aces, the Martin Luther King Award, the Prix Italia, two Peabodys and two Monte Carlos, Jack Gold's career was a triumph of integrity. There will always be an audience and a need for the kind of films he made for television. Unfortunately, there seems no longer to be a television that understands that.

SIMON FARQUHAR

Jack Gold, television and film director: born London 28 June 1930; married 1975 Denyse Macpherson (one daughter, two sons); died London 9 August 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments