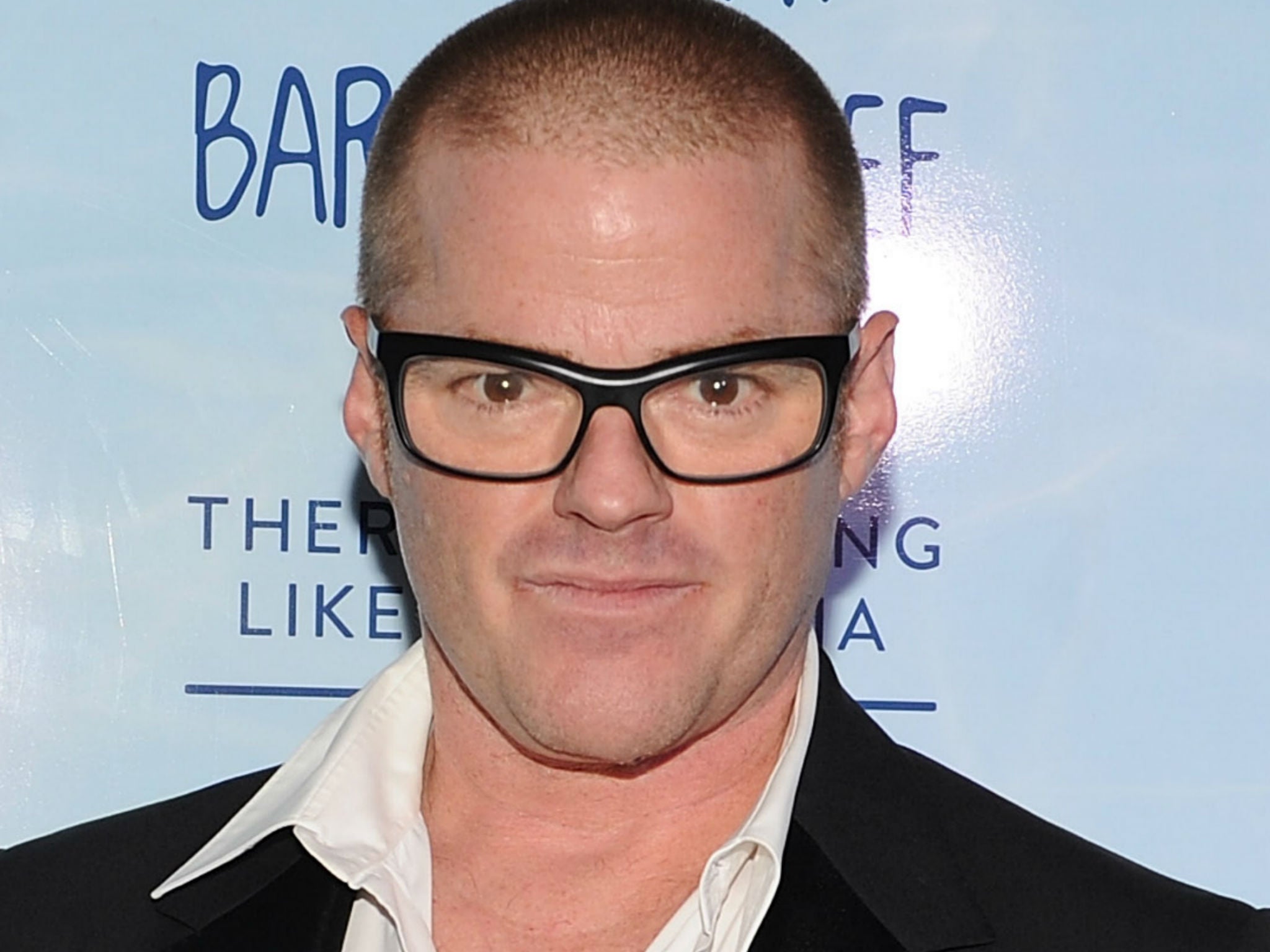

Heston Blumenthal on the problem with 'clean eating' trends: 'Isolating and excluding food groups does more harm than good'

The Independent spoke to the chef recently named one of the 175 faces of Chemistry

Self-proclaimed “chef first, scientist second” Heston Blumenthal has been a pioneer of British cooking for over 20 years, ever since he transformed a Berkshire pub into the iconic Michelin-starred restaurant, The Fat Duck, in 1995.

After opening more restaurants, writing numerous books and newspaper columns and developing ranges for Waitrose and Sage, Blumenthal has also fronted television series such as Heston’s Fantastical Food, creating his unconventional signature concoctions such as snail porridge and bacon and egg ice cream.

Blumenthal has long advocated food and cooking to be considered more of a science and coined the term “multi-sensory cooking”. He was recently introduced into the Royal Society of Chemistry’s “175 Faces of Chemistry”, with Yuandi Li from the RSC naming him “an inspiration” – all this despite failing his Chemistry O-Level.

The Independent spoke to Blumenthal about Major Tim Peake’s dietary requirements, why eating insects might be a big source of our diet sooner than we think, gender equality within cooking and why “clean eating” trends could do more harm than good.

You’ve been named a ‘face of Chemistry’ by the Royal Society of Chemistry (where you are also a fellow) and you’ve long advocated food to be thought of as a science. If food was considered more of a science, what benefit to people/society do you think this would have?

If people viewed cooking and eating food in a more empirical, precise way, I think they would become more aware of its importance when it comes to their physical and emotional wellbeing. This objective perspective doesn’t make cooking a cold, calculated process - in fact it’s quite the opposite – it encourages failure and creativity. Eating is such an essential part of everyday life that people often forget how exciting, experimental and joyful food can be.

As we grow older we stop asking questions. And that’s what science, and to a larger extent cooking should be about – challenging convention and asking questions. I failed my O-Level Chemistry, I was terrified of it, but through cooking I discovered this whole new world that had been previously unavailable to me. If people recognised food as a science, they would honestly enjoy it so much more.

Do you consider yourself to be more of a chef or scientist?

I’m probably a chef first and a scientist second. But they’re not mutually exclusive - the disciplines cross over and inform one another all the time. When I first read Harold McGee’s On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen back in 1985, I began to understand cooking as a skill, an art form, a part of everyday life, but also as a science. This can mean everything from the chemical component of a dish to the psychological impact it has. My first restaurant, The Fat Duck, is as much about the food and the power of nostalgia as it is about science. It uses a variety of scientific methods in order to enhance flavour and texture, as well as equipment like distilleries, centrifuges and molecular databases to enrich the experience. I may have Michelin star restaurants, but I’ve also published scientific papers with the University of Reading and conducted multi-sensory experiments at Oxford with Charles Spence. All of that work informs and influences my knowledge as a chef.

You have one of the few restaurants in the country to be awarded 3 Michelin stars, have written numerous cookbooks, got a food range, presented TV shows and so much more. Which aspect of your career are you most proud of?

I’m really proud that my food and restaurants have helped put the UK on the cooking map. French classic cooking has had such a hold for decades but it’s really good to see that has changed and with The Fat Duck I have always done things a bit differently. I’m very proud to be pioneering multi-sensory cooking and am particularly excited about my work researching the nostalgia and history of food.

What do you think about the way food is taught to children in schools?

I feel like not enough importance is placed on a skill you will rely on for the rest of your life. Cooking is the only subject that encompasses biology, physics, history, maths, English and chemistry, to name a few. It would be nice if it were acknowledged for its necessity and versatility.

I am currently working with the Oxford, Cambridge and RSA exam body to create a new food GCSE. It will replace the old food technology course and has a particular focus on the science and nutrition of cooking. Our current education system can often be too efficient, too narrow, relegating imagination to your childhood years. Our relentless pursuit of results has inevitably stifled creativity. I would like our GCSE to allow children to experiment and play, all the while learning deeply practical skills that will ultimately stay with them for life.

Should it be approached more as a ‘science’?

Absolutely. Over the next year we’re working towards adding some modules into the syllabus that focus on the senses and involve hands-on experiments. Back in 2005 I collaborated with the Royal Society of Chemistry to create Kitchen Chemistry, a textbook that was distributed to every school in the UK. It was important to me that the subject started to be aligned and associated with science, in both theoretical and practical terms.

Do you think enough is being done in schools to teach children the importance of food and how to cook? It’s a well-known stereotype that many young people find themselves stuck and unable to cook when they leave home?

It’s all too easy to marginalise traditionally non-academic subjects - but as my whole career hopefully illustrates - working with food or any other craft can open up fields of study you may have otherwise missed out on. We’ve seen a big decline over the past decade in students taking home economics - the course normally associated with cooking. I’m hoping that my GCSE will encourage kids to have some fun with it and that it will appeal to both boys and girls. It’s crucial that we stop associating cooking as an exclusively feminine, domesticated activity, as it’s reductive and harmful to both sexes.

You recently designed food for Major Tim Peake to eat in space. How did you decide what would be best for him and what things did you have to consider when designing the menu?

This was a huge project that spanned nearly two years. I worked very closely with Tim before his mission in order to create emotionally resonating dishes that would remind him of home. In the end, the food we created was based on the thing Tim said he would miss most about our planet – nature. I wanted to tap directly into his nostalgia and reconnect him to his loved ones, for example, we developed a sizzling sausage dish that had a pop-up campfire book containing the smell of sausages cooking on a fire – this tied into Tim’s childhood memory of camping trips.

I also had to take into account a number of unfamiliar, alien demands. The food had to be dried in cans at 200 degree Celsius for two hours to make it suitable for space and we brewed our cup of tea in micro-gravity, decanting it from one pouch to another. It was a completely new way of working. Saying that, I found these constraints quite liberating, you end surprising yourself.

What are your thoughts on the ‘clean-eating’ trend that continue to dominate Instagram and social media?

Isolating and excluding certain food groups I think often does more harm than good. I believe if people want to lose weight, exercise is far better for the body and soul.

Do you think pressures to ‘eat clean’ and stick to strict diets take the fun out of food?

Food should make you happy. It should never mean restriction and guilt - it should be about enjoyment. We should always be wary of self-censorship, especially when it has spurious health claims attached to it. Food has always played a huge role in our levels of happiness and a varied diet makes for a healthy body – why deny yourself that?

People news in pictures

Show all 18Food and eating trends are always changing. What is the future of food in your opinion?

All of us will be introduced to different foods over the course of our lifetimes to counter balance carbon and methane emissions from industrial scale farming. People are now experimenting with insects as a viable source of protein with limited costs to the environment and I wouldn’t be surprised if eating insects became widely accepted in the West in the not too distant future. Scientists are creating meat made up of grains and amino acids and 3-D printing has the potential to drastically change the way we produce and consume food. All of this work is incredibly exciting and science really is the driving force behind a lot of innovation in food at the moment. We are slowly beginning to discover a real connection between our chemically charged emotions and how they are influenced by what we eat.

As we noted earlier, you’ve done so much in your career. What is next for you?

The Fat Duck re-opened last year and that is still very much on a journey, one that I’m deeply involved in. I also have exciting plans in Australia that are keeping me busy, as well as developments in health and future tech. I will continue to ask questions and see where that takes me.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies