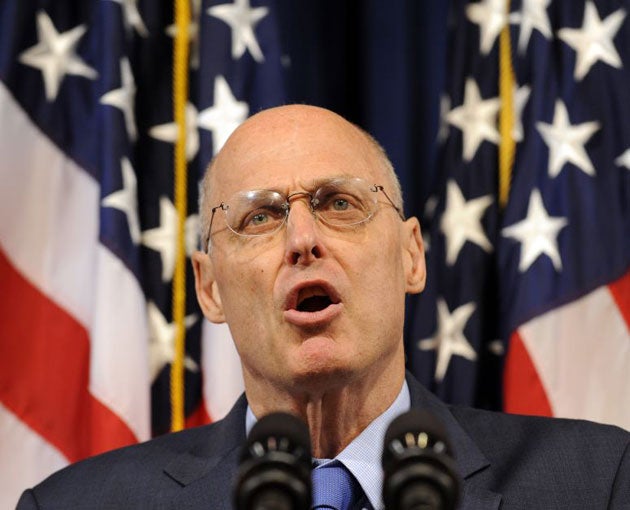

Hank Paulson: Give him credit

It is generally an ominous sign when the US Treasury Secretary appears in the news bulletins – and he has been showing up a fair bit of late. A reluctant appointee, the ex-bank boss is fighting hard to save the global economy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There was a pleading headline in one of the financial newspapers this week: "Take the weekend off, Hank". Not likely. For much of this year, the US Treasury secretary, Hank Paulson, has been as much a fixture on the weekend news bulletins as clips from the Sunday political talk shows or the latest election campaign headlines. And when he appears, it is never good news.

The turmoil on the world's markets means Paulson has had to work a lot of weekends – but thank goodness for him. While other men might be washing the car or watching football, this 62-year old multi-millionaire, lured reluctantly into the Bush administration from a $37m-a-year job at the top of Wall Street, has come to prop up global finance on a Sunday afternoon not once, or even twice, but three times – and he might just do it again tomorrow.

Tall, thick-necked, solid; Bush's economic policy supremo has been the world's chief firefighter as the credit crisis ignited blazes across the financial system. Venerable Wall Street bank teetering on the edge of collapse? Cometh Paulson. A consumer economy in need of a shot in the arm? Cometh Paulson again. Mortgage system on the brink of failure? Cometh Paulson one more time. If the US avoids a rerun of the Great Depression, historians may well lay a lot of the credit at his door.

Half a trillion dollars of Wall Street's mortgage investments have been wiped out since the US housing market crashed and millions of Americans began defaulting on loans they should never have been allowed to take out.

For a year now, fear has stalked the global markets and historic financial institutions have been brought to their knees, some of them overnight. A poisonous cocktail of interconnected trading relationships and stifling opacity has meant that the failure of any one player could bring down the whole.

For those in the direst straits, the aim has been to stumble as far as the weekend, then use the breathing space between close of trading in New York on Friday and the reopening of Asian markets to work out a proper rescue.

Having given 32 years of his career to Goldman Sachs, the mightiest of all the investment banks, including eight as chief executive, Paulson knows all the main players on Wall Street and sees better than most the horrible web of trading relationships and exotic financial products that has brought such danger. He knows what is possible and what is not, he knows where to exert pressure – and on whom – and he knows how to get his way.

When Bear Stearns was dying, he helped cajole on that fraught Sunday in March a reluctant JPMorgan Chase into buying the investment bank, lock stock and barrel. And he insisted that Bear Stearns shareholders face near-total wipeout as a lesson to future generations of investors and managers.

Critics argue that Paulson has been using taxpayer money to bail out his friends on Wall Street, but he counters that he has only acted at all in extremis. When the mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac faced a crisis of confidence, he bounded down the steps of the Treasury building on Pennsylvania Avenue on a Sunday in July to assure markets that the government would do what was necessary to keep them afloat – even though the Wall Street banks which compete with them have long wished for their demise.

These exertions have hardly been fun, but they have erased that doubt Paulson had about taking the job in 2006, when he feared joining the fag end of an administration that had demonstrably run out of political capital. He thought he might end up doing little and achieving nothing that lasted.

That would certainly have been no fun at all for a man who had spent a life consistently bulldozing his way through opponents, from the football fields of Dartmouth College – where he first got the nickname Hank the Hammer as an offensive linesman in the Sixties – to the boardrooms of Wall Street.

Henry Merritt Paulson Jr was born 1946 to Christian Scientist parents in Palm Beach, Florida, the son of a wholesale jeweller. The family moved to Illinois where he excelled at school, naturally, and was an Eagle scout in the Boy Scouts. His English degree was followed by a job at the Pentagon and then in the Treasury and Commerce departments in the Nixon administration, after which he went to business school at Harvard and then into investment banking with Goldman Sachs.

Most notably, he emerged victorious in the power struggle with Jon Corzine, who was forced out as the joint chief executive with Paulson in the run-up to Goldman Sachs' flotation in 1999. Later he was instrumental in ousting Dick Grasso as the chairman of the New York Stock Exchange and installing his protégé John Thain as a replacement with a brief to modernise the exchange as demanded by its biggest users, among them one Goldman Sachs.

Grasso still refers to Paulson as a "snake". Paulson says snakes are among his favourite animals.

A parallel life would have taken him not to Goldman Sachs and the Treasury but to a quieter existence as a park ranger, he says. Indeed, he often startled colleagues by bringing birds of prey into the chief executive's office at Goldman and would harangue business associates into donating to The Nature Conservancy, the environmental group of which he was vice-chairman until heading to Washington. It was to environmental and other charitable causes that he handed $100m of his fortune in 2006, and to which he says he will pass most of the rest of his estimated $500m wealth after his death (minus a small trust for the grandchildren).

Before agreeing to take on the job of Treasury secretary, Paulson extracted a promise that he would have more clout in the position than his predecessors John Snow and Paul O'Neill, who George Bush largely sidelined .The President promised wide influence over economic policy but Paulson struggled to shake the impression that he was a reluctant appointee.

He was reluctant enough to uproot from Illinois in 1994 after getting the No 2 job at Goldman. He and his wife, Wendy – a sweetheart from university – had built a life on a five-acre site carved out of the family farm, where the couple raised raccoons, alligators and turtles among a menagerie of other animals – and two children. Since taking over as Treasury secretary, he has had to forego his bird-watching rambles in New York's Central Park that were his prelude to a day in the office.

His green credentials have sometimes led Paulson into controversy. Goldman shareholders criticised the bank's donation of 680,000 acres of ecologically sensitive land on Tierra del Fuego island in Chile to the Wildlife Conservation Society, a charity that Paulson's son Merritt advises.

Despite the revolving door between Goldman Sachs and government, and for all Paulson's credentials as a lifelong Republican and a Bush fundraiser, he has always seemed like a square peg in an administration full of round holes. As well as being an environmental activist of many years standing in a government that expressed scepticism for the science of climate change, he went to Washington without the political polish that many on Wall Street have obtained on the New York cocktail party circuit and in the Hamptons, the upstate playground for bankers which he had always shunned.

He initially found the capital a frustrating place to be, seeing his attempt to kickstart social security reform go nowhere and discovering that his extensive contacts in the Chinese government – forged on 70 trips seeking business for Goldman – would not translate into economic concessions to the US government.

Paulson is prone to getting angry in argument, to thumping the table, and getting tongue-tied in public debate. He is not prone to Obama-ish oratory. "I'm not an inspirational leader, I'm just not," he once said. Where he gets his respect instead is through his undoubted intellect, and the commanding presence demanded by his bulk and his piercing blue eyes. Now, in the unchartered territory of the credit crisis, things are even stranger. A die-hard believer in free markets, in an administration that made relaxing regulations on business an article of faith, Paulson is presiding over the biggest government intervention in financial markets since the Great Depression.

Last Sunday, Paulson announced that federal regulators were seizing control of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, who between them have underwritten half of all the mortgages in the US; about $5.4trillion of home loans will now effectively be guaranteed by the taxpayer. He announced $6bn of funding to prop up the pair, and that is just for starters. The Treasury could end up buying $100bn or more of the mortgage bonds issued by Fannie and Freddie, and pumping $100bn cash directly into the two companies.

In fractious exchanges in Congress after he first promised to prop up the two companies, Paulson told Republican colleagues that he hated what he was doing as much as they did. But letting Fannie and Freddie fail would have dried up what remains of the mortgage market, sending house prices spiralling and fuelling a flight of international capital from the US, with devastating consequences for the US economy.

This weekend, the fight is on to save Lehman Brothers, which at 158 years old is the oldest of the major investment banks. Throughout the week, behind the scenes, Paulson has been telephoning his old contacts on the Street to monitor this latest crisis as confidence has drained in Lehman's ability to survive and to try to head off a situation that will put the US taxpayer on the hook for yet more of Wall Street's losses. If you see him on the TV tomorrow, it won't be good news.

A Life in Brief

Born 28 March 1946, Palm Beach, Florida.

Family Son of Marianna Gallaeur and Henry Merritt Paulson Snr, a wholesale jeweller. He met his wife Wendy at Dartmouth College. They have two children.

EARLY LIFE He majored in English at Dartmouth, where he was a member of the Phi Beta Kappa academic honour society. He was also a Boy Scout and a talented American Football player.

Career Staff assistant to the assistant Secretary of Defence at the Pentagon from 1970 to 1972. He served as staff assistant to President Nixon until 1973. He joined Goldman Sachs in 1974 and became the chairman and chief executive in 1999. In 2006 he was named the US Treasury Secretary.

He says "Government intervention is not something that I came here wanting to espouse, but it sure is better than the alternative." – on bailing out Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

THEY SAY "He is acting like the minister of finance in China." – Republican Senator Jim Bunning of Kentucky on the bail out.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments