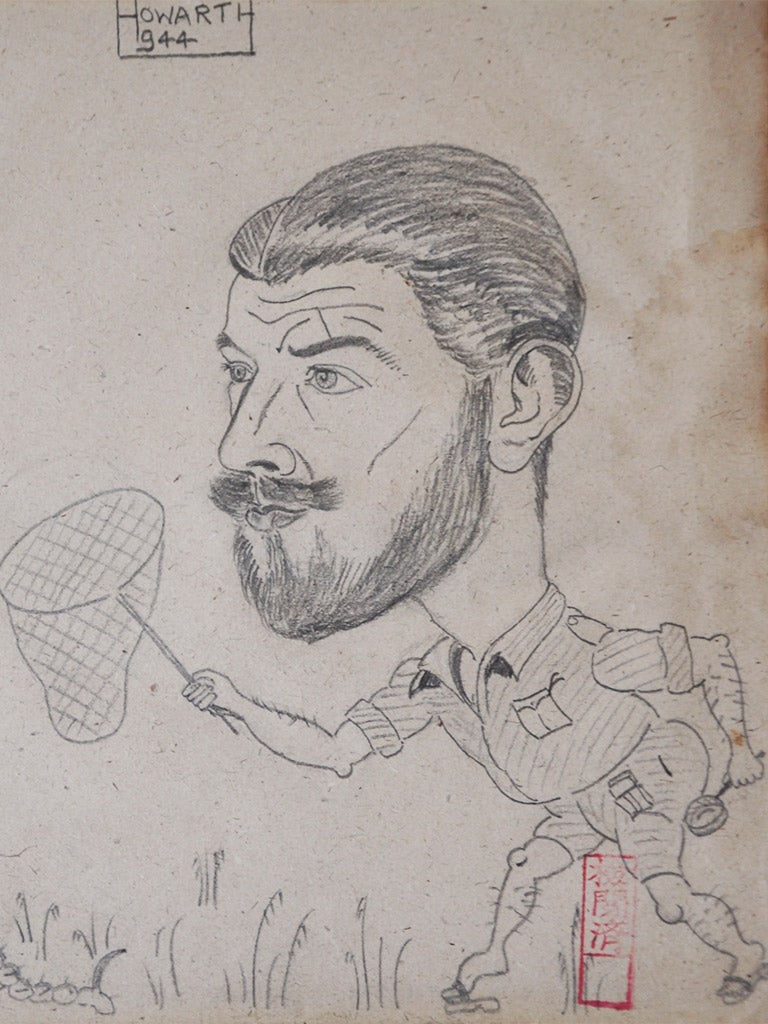

Graham Howarth: Entomologist who became a prisoner of the Japanese but was able to build a large collection of butterflies and moths

Singapore became malaria-free, partly through Howarth's work in the 1940s

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Graham Howarth, who has died at the age of 99, was a specialist in butterflies and moths at the Natural History Museum in London. At the outset of the Second World War he was responsible for selecting and moving the most important parts of the Museum's collections into a makeshift air-raid shelter in the basement. Enlisting in the Army Medical Corps, he became a volunteer fire fighter during the Blitz and was awarded the British Empire Medal for gallantry.

In 1941 he was posted to Singapore and given the task of identifying and then destroying the breeding grounds of malaria-carrying mosquitoes. Partly through his work, Singapore became malaria-free. But on his 26th birthday, on 15 February 1942, the British army surrendered to the Japanese in Singapore and Howarth was made a prisoner of war.

With wry humour he recalled the moment of his capture: "There are times when the more self-conscious of us feel uncomfortable when, armed with entomological paraphernalia, we are confronted by the public. I was never more so than when I encountered the enemy armed only with a tin helmet and a larval scoop! My collection and gear was dispersed by a shell, fortunately a small one, but I managed to salvage and amalgamate it again."

Howarth's internment began in the notorious Changi jail in Singapore where his cramped first quarters were in a latrine. He was later transferred to Jimsen in Korea, where he spent the rest of the war in forced labour. In what he described as "a war against boredom, starvation, pestilence and death", he continued to study insects with the help of a net made from a piece of wire and a scrap of mosquito netting.

"Collecting gave me something to think about," he recalled. "As long as you exhibited a certain amount of respect for the guards, and didn't stick your head above the parapet too often, you were all right. Of course, with a butterfly net, I would tend to be a bit conspicuous, but I didn't flaunt it, shall we say." The other prisoners called him "The Prof".

Howarth secretly preserved his collection of 1,115 butterflies, 347 moths and 100 other insects in cigarette tins and managed to smuggle it home after liberation in August 1945. It includes a moth, Apatelea cerasi, which he bred from larvae found on flowering cherry and which proved to be new to science. The collection survives to this day in the Natural History Museum. His entomological diary, with its Japanese censor's markings, was left to the British Entomological Society.

Howarth nursed no rancour against his Japanese captors. He became an authority on Japanese butterflies and described a number of new species. The Japanese in their turn honoured him with life membership of their Lepidopterological Society and named a new genus of hairstreak butterfly, Howarthia, after him.

Howarth was born in 1916 in Muswell Hill, a leafy suburb of North London. He was fascinated with wildlife from boyhood, particularly through holidays in the Breckland of Suffolk with his grandfather, the naturalist Harry Chapman. At school he won prizes for art and natural history and was taken under the wing of two famous entomologists, Edward Cockayne and Bernard Kettlewell. His other hobbies were fishing, stamp collecting and music. For a while in the 1930s he was the drummer in a swing band.

In 1936, Howarth embarked on a lifelong career in the Entomology Department of the Natural History Museum, beginning by sorting and mounting specimens in the Department's Setting Room. He ended his career 40 years later as a Senior Scientific Officer and an authority on butterflies and moths in Britain and around the world. Towards the end of his career he rewrote South's British Butterflies for Frederick Warne, which became, for a while, the standard text on British butterflies.

In retirement, Howarth was involved in conservation measures to save the threatened Large Blue butterfly. He and his wife Helen, who he met across a table in a Lyons Corner House, entertained and travelled abroad, usually on entomological outings. Howarth was the longest-serving member of both the Amateur Entomologists' Society and the South London Entomological Society (now the British Entomological Society). A lecture theatre at the latter's headquarters at Dinton Pastures is named the Graham and Helen Howarth Room in their honour.

Howarth was a dapper, neatly-dressed man with a moustache and goatee beard reminiscent of Colonel Sanders of Kentucky Fried Chicken fame. He had a tendency in later years for uninterruptible monologues, but could beguile most listeners with his old-world charm and manners and his self-deprecating humour. Despite his harsh experiences as a POW, he retained good health almost to the end of his long life. During his 40 years at the Natural History Museum he made many entomological friends and helped many young entomologists on their career path.

PETER MARREN

Thomas Graham Howarth, entomologist: born Muswell Hill, north London 15 February 1916; Natural History Museum, Senior Experimental Officer (Lepidoptera) 1936-76; Royal Army Medical Corps 1939-45; British Empire Medal 1941; married 1952 Helen Wayman; died Lymington, Hampshire 8 April 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments