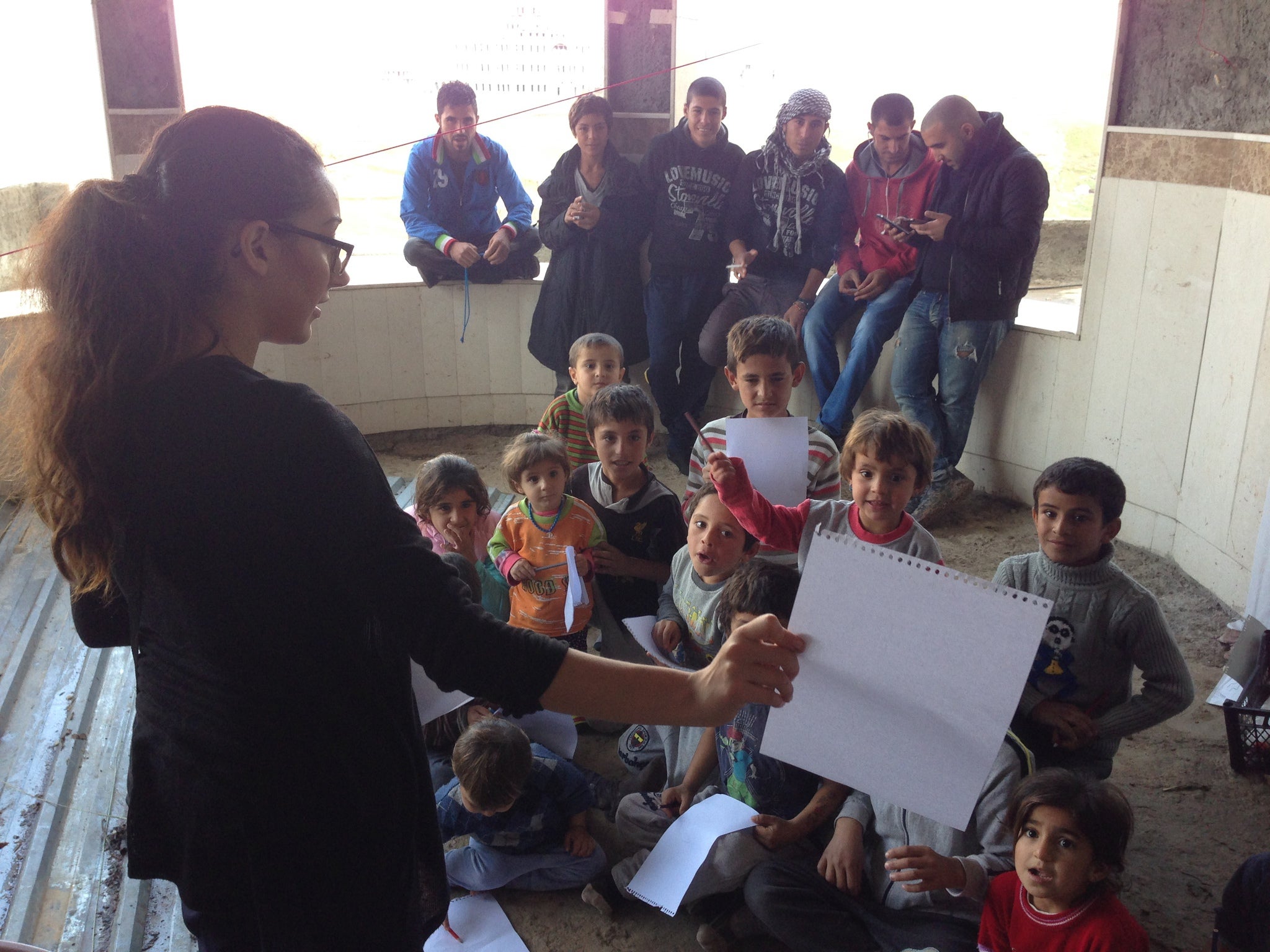

Delal Sindy profile: Meet the woman who quit her job, paused her studies and left Sweden to help Yazidi women and children fleeing Isis

The 24-year-old is carrying out vital aid work

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ten months ago, aid worker Delal Sindy quit her job in Sweden, suspended her studies and travelled to Iraqi Kurdistan to help men, women and children fleeing Isis militants after the terror group crossed over into the Sinjar mountains.

Sindy first caught the attention of British and Swedish media in May when she began posting the traumatic experiences of Yazidi girls she encountered on her Instagram page. She continues to work with those who have escaped militants' brutal clutches.

Who is she?

Sindy, 24, is half-Swedish, half-Kurdish and left Sweden to volunteer after Isis launched its insurgency across northern Iraq and Syria.

“I handed in my notice to quit my job and paused my studies. I also gave up my apartment," she told The Independent. "Finally when everything was done, I booked a ticket to Kurdistan in October. One week before my flight I got in touch with other volunteers who were going to take the same flight as me and they were going to stay in my hometown Zakho, so I asked to join their organisation (Kurdish Diaspora).

“I was a volunteer with Kurdish Diaspora for two weeks and we helped the internally displaced people with medication, psycho-social support and distribution of NFI's. After these weeks, they went back to Sweden. But I stayed because I couldn't leave, it didn’t feel right in my heart, and now I have been here for ten months and it feels like the best thing I have done in my life.”

"Yesterday, Shingal/Sinjar mountain. We distributed boots, clothes, socks, heaters, flour and hygiene-kits"

Who is she helping?

A report by Human Rights Watch found Isis fighters are committing widespread, organised and systematic rape and sexual assault on Yazidi women and girls in what may amount to crimes against humanity.

Sindy has worked with a number of Yazidi women and children who have escaped their captors after being sold into sexual slavery. She also works with families who have been displaced by Isis militants. All have harrowing stories to tell.

"Six months ago on Mount Shingal/Sinjar. It was the craziest, coldest weather ever and 90% of the children were wearing sweaters, no jackets"

“The displaced that I am helping are mostly former Isis captives,” said Sindy. “I have seen it all.

“Some of the women have been whipped because of their unwillingness to engage in sexual activities, clean Isis’ soldiers’ wounds, or cook and clean for them. Some women that Isis couldn't take advantage of sexually were shepherds or worked in their farms. Most women were abused sexually and raped on a daily basis.

“One of the oldest captives I have met was an 84-year-old woman who was forced to bake bread and cook rice and meals for the soldiers, and take care of disabled children. But there have also been some cases of muslim men who were forced to translate between Arabic, Turkish and English.

“I could go on for a week talking about what they have gone through and it wouldn't be enough time.”

Sindy says she works closely with Yazidi women and girls because many were apprehensive about approaching NGOs or aid organisations.

“They really do trust me and I do my best to help them in any way that I can,” she said. “If I can’t help them, I refer them to other NGOs working in the camps or skeleton buildings.

“It is a job that requires me to be on point all the time, not to show too much sensitivity but not be cold. Not be too helpful in a way that they become dependent, but also giving them the help that they need in order to manage their daily lives. The most difficult thing about this job is to know what they have been through and the outcome of these tragic and inhumane events.”

What’s next?

Sindy is now looking to open her own aid organisation, which she says will allow her to stay in Kurdistan. She also dreams of becoming a psychologist one day.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments