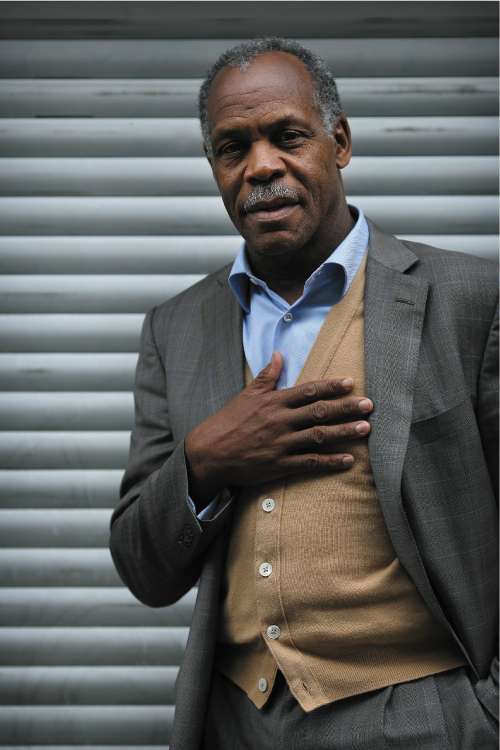

Danny Glover: Ready to shoot

The 'Lethal Weapon' star gets angry when accused of making propaganda for his friend the socialist president. But why is this activist reluctant to help Barack Obama win the White House?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Barack Obama needs help. Struggling to cope with the impact of his former pastor, the rabid Reverend Jeremiah Wright, he needs support from a man of integrity. A man trusted by voters of all colours. A man they have seen blow bad guys away with his great big gun, then say something really funny.

Danny Glover could be that man. The co-star of the hugely popular Lethal Weapon movies is also a political activist who has spent his whole life campaigning for change. His active support could deliver votes to Obama. But if he were to come out against the presidential hopeful ahead of this week's two primaries, he could blow those votes away. So what is he going to do?

"What does it mean to have a black president?" asks Glover, rhetorically, slurping his way into a huge bowl of chopped fruit in a London hotel. "Does it mean anything other than having a white president, or another male? Does it mean anything more?"

Obama clearly hasn't convinced the actor, who backed John Edwards for the Democratic nomination at first because he "didn't talk about 'change' in a vacuum". Like Obama? He nods. "A campaign is built on certain principles that get you elected. A movement is based on how we really envision the nuts and bolts of change." So far Obama has built a campaign, he says. "We need a movement."

As for Hillary Clinton, she's "a career politician". He fears the choice between a black man and a woman is not as revolutionary as it seems. "Does it mean we are seduced, once again?" By people who look different but turn out to be just the same old kinds of politicians in disguise, is what he means.

Glover's taste is for something stronger. He's playing a leading role in his own international drama right now. Hollywood hustlers would pitch the plot this way: wicked Latin American dictator – likes a uniform, you know the stereotype – seizes power in an oil-rich country and sets out to spread revolutionary socialism, threatening liberty, freedom and the American way. Who will stop him? Enter Danny Glover, action hero. Great casting. Yay! Eat lead, red menace! But hang on, what's this? Danny's shaking the bad guy's hand. They're hugging. Oh no! Now they're making a film together ...

"The President and I are friends," Glover says of Hugo Chávez, leader of Venezuela and scourge of the White House. Chávez calls George Bush "the devil" and is so determined to resist US influence that he has set up his own film studios to overthrow "the dictatorship of Hollywood". So what is he doing, hiring a Hollywood legend? And why is Glover interested?

"It's a business deal," he says, looking like an executive abroad, in his open-necked, pastel blue shirt and olive-coloured suit. Glover is 61 years old now, and the familiar moustache and cropped hair are dusted with white, but he still moves with the slow, angular elegance that made him the perfect foil to the manic intensity of his Lethal Weapon co-star, Mel Gibson. He speaks slowly, too, as if supernaturally calm (or jet-lagged) – until asked about Chávez.

"If you get into attacks on me about how I'm a tool of propaganda, and all that, come on!" says Glover, his drawl now a bark that startles a waiter in this quiet Bloomsbury hotel. "That's so sophomoric. That's so juvenile."

Sorry, but they're not my words. A Republican senator slated him for being "part of the Chávez propaganda machine". He has also been compared to Lenin's "useful idiots", liberal Westerners who supported the Soviet regime without knowing the full story. "I can't even respond to that, you know what I'm saying? This is a business relationship."

Not quite just that – although the deal, as he describes it, is a simple one. The government of Venezuela is investing millions of dollars in a film about Toussaint L'Ouverture, leader of the slave revolt in Haiti in 1791. Glover is about to start shooting it. The hope is for a profit, using local skills where possible so that much of the money stays in the national economy. "It does look like a good deal."

But then you have to stir in the politics. Chávez is loved by his supporters, the Chavistas. His opponents loathe the nationalisation of industry and the high taxes imposed on foreign oil companies. The US sees him as a security threat. This particular individual, I say, attracts strong emotions. "The individual and the government were elected by a majority of the people," insists Glover, agitated. "They do not control the press, they are not authoritative in that way, they do not censor what people have to say in that country..."

Condoleezza Rice has attacked Chávez's record on press freedoms and human rights. (To which the Venezuelan Foreign Minister responded: "How many prisoners have they got in Guantánamo Bay?") So will Chávez tell Glover what to put in his film? "Huh?" I repeat the question. "No! I have a business relationship with them. They saw the script."

Chávez, he says, "is only a manifestation of the will of the Venezuelan people". That sounds eerily like a presidential statement. So does this: "The changes happening in Latin America are enormous. We've been under the heel of US political and economic aspirations for centuries." Notice the "we"? This is Glover, an American actor, sitting in the breakfast room of a hotel in London, talking about events in Caracas and saying: "What's happening here is extraordinary."

Glover is more than a bit extraordinary himself, for a Hollywood star. Most adopt causes for the sake of their image, or as an antidote to the essentially ephemeral nature of their work. Glover only became an actor because he believed it would enable him to agitate for change.

Born in 1946 to politically active parents, this "child of the civil rights movement", as he calls himself, grew up in San Francisco. He led the longest student strike in US history, then became a community worker before joining the Black Actors Workshop. His first major film role was a forceful performance as Mister in Steven Spielberg's The Color Purple. All his life, he has juggled huge-money Hollywood projects like that (or the rather less good Predator 2) with leading, directing or producing films such as Bamako, an award-winning drama about love and globalisation in Mali. Despite critical acclaim, such films are hard to get financed. "The perception is that these are black films and won't get a wide audience. I need to find a way to prove that wrong." That's another reason why he's happy to do a deal with Chávez.

His latest lead role is in Honeydripper. A beautiful, slow but seductive story by John Sayles, it is set in the Deep South, where his mother was born. It is 1950, the cotton is in the fields and the white sheriff is in control, but change is coming.

Glover plays "Pine Top" Purvis, a piano-playing bar owner struggling to get by as juke boxes entice all his customers elsewhere. On one level, the story is about the blues and the impact of the electric guitar. But it is also about segregation and the way movements grow out of individual acts of resistance. If that sounds po-faced, there are some great tunes – and lines that must have audiences cheering in the credit-crunched US. "Everybody gets credit," howls Pine Top. "It's the American way!"

Not any more, says Glover. "The world is built on this tenuous game some people refer to as casino economics. Nobody expects the bottom to fall out of the whole thing." This is not some casual pet project: he can quote economic history and statistics until you long for a nice big explosion.

He wants the restoration of a real safety net for the poor of America. "Most of the wealth earned there over the past 35 years has gone to people already in the top 5 per cent of earners." He must be one, I say. "That's an assumption." Yes, but a reasonable one, surely? "I may be like, you know, Anita Roddick, who gave a lot of her money away." Is he? "I support a lot of stuff, and I give a lot of money away."

Suppose, he argues, he made a film a decade ago for – hypothetically – $5m. "I may have not done anything significant to make money since then. That's only $500,000 a year."

Still sounds a lot to me. Even more, surely, to a victim of Hurricane Katrina, or anyone else he meets on the many humanitarian trips he makes for the exhausting list of charities he supports. Glover is not some help-the-Tibetans photo-opportunist. He spends an astonishing amount of time on the road. On May Day, for example, he spoke at a rally for the longshoremen trying to close the ports on the US West Coast, in support of workers' rights and an end to the war in Iraq.

Not many laughs there. I haven't heard him laugh once. Why do it all? Why not give up and go to Malibu like his superstar mates? "Inspirationally, [this is] a legacy that comes largely from my parents," he says. They were postal workers and activists in the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People. "I have images, as a child, of the Montgomery bus boycott," he says. The college strike got him jailed. "At 20 years old, there's a lot of bravado. We felt we were the embodiment of change."

He was working for the city in community development when he married Asake Bomani in 1975. They had one child, but divorced after 24 years. Surprisingly, he still lives "in a very modest Victorian house about 10 blocks" from where he grew up, in the Haight Ashbury district of San Francisco. "I like walking to the Golden Gate Park, going to the same hardware store I've gone to for almost 40 years. I like the idea of being in a place where you have memory, and that constitutes a part of the way you see yourself."

It is, he says, a question of trying to retain your humanity whatever happens. "I really believe we can be architects of our own rescue. We will all face judgement," he says, speaking in the authoritative drawl used for his most portentous lines. "At the end of my time, I want somebody to say: 'He tried to do the right thing.'"

With that, Glover pauses. He sees a bad guy outside that he recognises, leaps up from the table and jumps through the hotel window, sending splinters of glass flying everywhere. Running down the street, he shouts his old Lethal Weapon catchphrase back over his shoulder: "I'm getting too old for this shit!"

Does he really? No, of course not. Danny Glover doesn't do that shit any more.

'Honeydripper' is released in the UK on Friday

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments