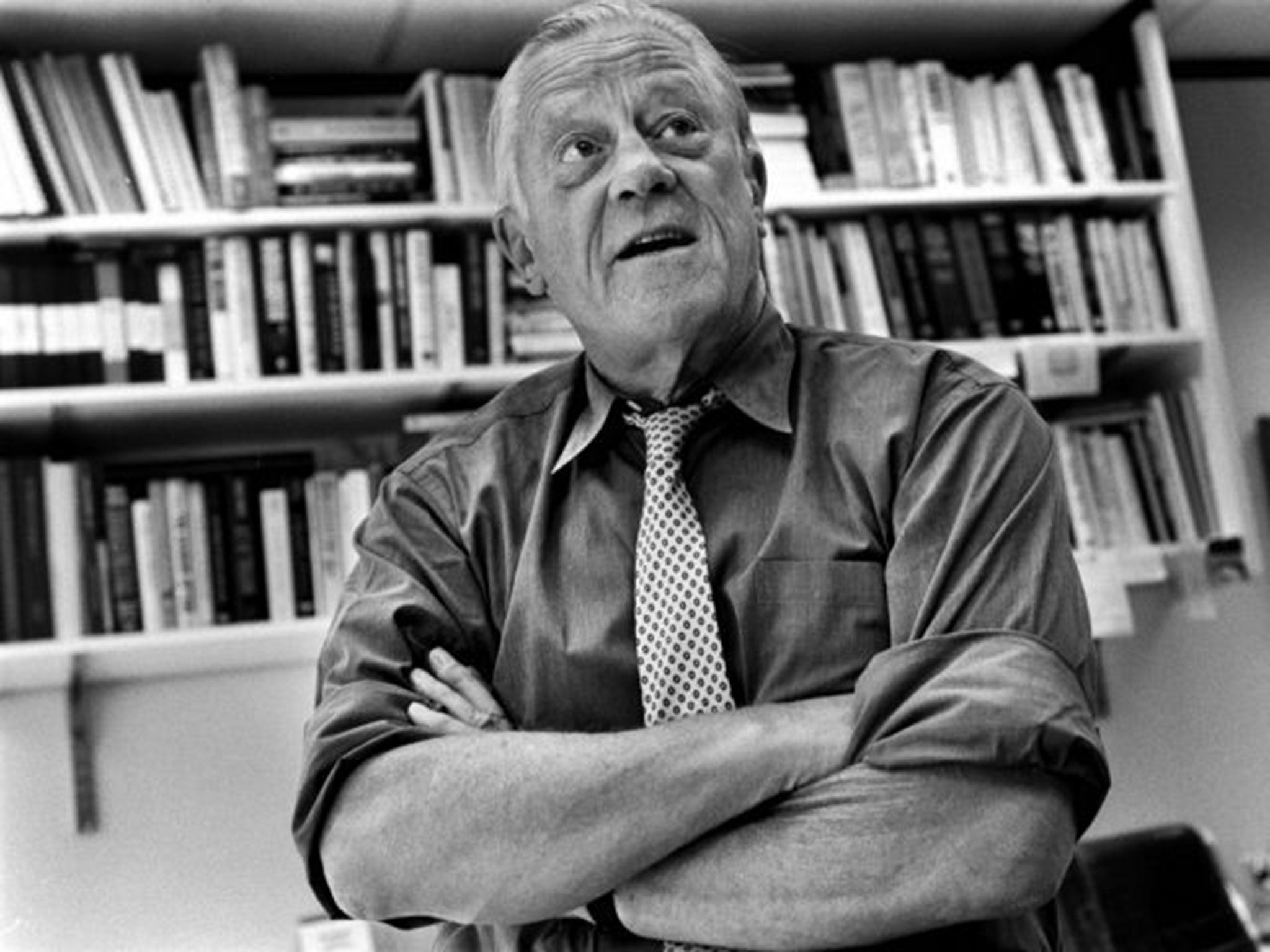

Ben Bradlee: One of the finest editors of his generation, who led the 'Washington Post' through the Watergate scandal

The scandal forever changed the American press and its relationship with government

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ben Bradlee was the apotheosis of the hack. He was the journalist that almost every journalist wished he could be: one of the greatest editors of his age, whose paper laid bare the biggest political scandal in American history, all the while oozing a swaggering star quality that would have made him a stand-out in any walk of life.

The scandal was Watergate, which forever changed the American press and its relationship with government. The dogged, initially lonely, pursuit by Bradlee's Washington Post of the story behind what the White House dismissed as a "third-rate break-in" led ultimately to the resignation of Richard Nixon. The Post for a while became the most famous newspaper in the world, and Bradlee was its public face. Suddenly, for young graduates, journalism was the most heroic and desirable trade of all.

Bradlee was raffish and rakish, rude and impossibly charming. A fellow Navy veteran once described him as having " the face of an international jewel thief." If anything, he was more glamorous than the film star – Jason Robards – who portrayed him in All the President's Men, the hit 1976 Hollywood movie about Watergate. Like every journalist, he adored gossip – especially with his lifelong pal, the humorist and columnist Art Buchwald. He loved using salty language, and relished his celebrity. He also realised, and was the first to admit, that in the great race of life, he started in pole position, in his own words "dealt a really good hand by the powers that be."

There was good fortune from the start. Benjamin Crowninshield Bradlee hailed from the Boston Brahmin establishment. During the Depression he attended a smart private school and took regular family holidays in Europe. He was a fourth-generation Harvard graduate, the 51st member of the Crowninshield clan to attend the Ivy League university.

At 20 he graduated. He got married, and went off the next day to join the Navy and fight in the Pacific. He had a good war. "They were certainly the most important two years of my life, then and maybe now," Bradlee wrote in a marvellously entertaining 1995 autobiography, A Good Life: Newspapering and Other Adventures. "I had such a wonderful time in the war. I just plain loved it. Loved the excitement, even loved being a little bit scared. Loved the sense of achievement... Most of all I liked the responsibility, the knowledge that people were counting on me, that I wouldn't let them down."

In 1946 he helped start a New Hampshire newspaper, selling it two years later to become an $80-a-week police reporter at the Post. He wrote a riveting account of the 1949 race riots at Anacostia in black south-east Washington but the paper cut a deal with the city fathers and buried the piece inside the paper. "Un-fucking-believable," was Bradlee's outraged, typically profane comment.

Frustrated by his lack of progress, Bradlee quit in 1951 and became a press attaché at the US Embassy in Paris, before signing up as a foreign correspondent with Newsweek in 1953. Four years later he was transferred to Washington, rising to become Washington bureau chief – and then persuading the Post to buy the magazine. Niftily, Bradlee jumped horses to become managing editor of the paper in 1965, and editor three years later.

Was he lucky? Of course. He was lucky that a rainstorm in 1948 made him miss a train stop in Baltimore for a job interview at The Baltimore Sun, so that he ended up in Washington, where he found a better one on the Post. Then came Paris, the world's most glamorous capital, at a particularly interesting time.

Returning to Washington in 1958, he just happened to find himself the Georgetown neighbour of a young Senator from Massachusetts called John Kennedy. And if you do progress to a third marriage, what greater stroke of fortune than a long and happy one to Sally Quinn, a young reporter on the paper, 20 years his junior? But then again, as the great baseball owner Branch Rickey once observed, luck is the residue of design. A great performer makes his own good fortune, and Bradlee's performance at the Post bore this out.

When he joined, it was the second paper in town behind The Washington Star. Bradlee would change all that. He launched a pioneering Style section that was, like Bradlee himself, flashy and irreverent – and quickly imitated by newspapers across the land. With his trademark dress of power braces and bold striped shirts with white collars, he dispelled the then staid image of the Post.

Indeed, a backhanded measure of his success was the gradual decline of the paper after he stepped down as editor in 1991. For all its reputation, the Post returned to its former rather stodgy and provincial persona, while the Style section gradually became a shadow of its old self. Only recently has it regained some of its lost bravura.

Bradlee was a man of action, not ideas. His goal was stories which "grab the town by the throat", which made waves and got the Post noticed. Not for him long analyses or worthy opinion pieces. Washington and Bradlee were perfect partners. "He had a short attention span, in a town with a short attention span," the journalist and author David Halberstam once said of him.

In fact the real turning point for the newspaper was not Watergate, but the publication of the Pentagon Papers in June 1971. Under Bradlee, the Post had changed its stance on Vietnam. Though The New York Times, courtesy of Daniel Ellsberg, scooped the Post by a week on the Pentagon's secret history of the war, Bradlee realised that he too had to have the story to make the big leagues, even at the cost of defying a gag order and risking the future of the paper.

In the event, the Supreme Court, upheld the two papers' right to publish. The Post was now a certified rival of the Times. No less important, the fraught episode forged a bond of unity and trust between Bradlee and his proprietor Katharine Graham, without which the paper might not have had the nerve to pursue Watergate. "God bless her ballsy soul," Bradlee wrote in his memoirs.

Bradlee was no less ballsy. He was a natural leader, but a fine delegator as well. In the Kennedy and Johnson eras he might have played the games of power (one of the less believable parts of his autobiography is his claim that he had no idea of JFK's philandering – among others with his own then sister-in-law).

But under Nixon he resisted the fiercest pressure of the White House and stood unswervingly behind his reporters, above all Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, whom the Watergate story turned into legends. He did ask the pair to tell him the identity of "Deep Throat" (later revealed to be Mark Felt, as former deputy director of the FBI). At the time he was the only third party vouchsafed this privilege.

Watergate was not only Bradlee's finest hour. It changed American journalism. Thereafter the automatic assumption in newsrooms was that governments lied. No longer were the private lives of politicians off-limits. The press and the authorities entered into the adversarial relationship which is now the norm. Bradlee and the Post were fêted around the world.

But hubris, if so it might be called, was followed by nemesis – in the shape of Janet Cooke. Cooke was a young, highly-rated reporter who invented an amazing tale about an eight-year-old heroin addict in drug-ravaged Washington DC. It was one of those stories that was too good to check. Unfortunately it also won a Pulitzer Prize in 1981, and in the ensuing media spotlight Cooke was swiftly exposed as a serial fabricator. A humiliated Post returned the award. The deeper lesson was that the paper had itself become complacent and sloppy.

Bradlee retired as executive editor in 1991, becoming Vice-President-at-large – in effect the Post's ambassador and schmoozer-in-chief, enjoying family life and the high-powered dinner parties he and Sally gave at their Georgetown home. He was also a member of the board of Independent Newspapers. In 2013 President Obama bestowed the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the US's highest civilian honour.

To the end Ben Bradlee eschewed grand philosophies, of journalism or anything else. His main piece of advice to those asking for the secret of success was a lapidary high-school motto: "Our best today, better tomorrow."

RUPERT CORNWELL

Benjamin Crowninshield Bradlee, journalist: born Boston 26 August 1921; married 1942 Jean Saltonstall (marriage dissolved; one son), 1956 Antoinette Pinchot (marriage dissolved; one daughter, one son), 1978 Sally Quinn (one son); died Washington 21 October 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments