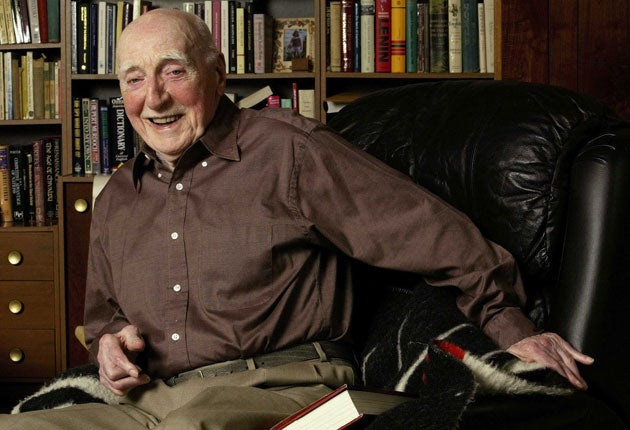

William Woodruff: Economic historian whose account of his childhood became a bestseller

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."Human motivation is too intimate to yield itself to the technical processes of the historian," conceded the economic historian William Woodruff in Impact of Western Man: a study of Europe's role in the world economy 1750-1960. This wide-ranging, statistics-driven work, published in 1966, did not give any hint of the extraordinary determination that had gained a seemingly diffident Woodruff notable academic posts around the world. Thirty years on, he published a rather different work, the autobiographical Billy Boy (1993), which seven years later was republished as The Road to Nab End and became a surprise bestseller.

The privations described in this account of childhood in one corner of Europe – Blackburn, Lancashire – brought a new perspective on his earlier comment that "there is nothing fundamentally new about economic growth (or decline) except our present obsession with it". He grew up amidst decline, and so appreciated later stability that he always cautioned against the excitability – as distinct from innovation – which brings bust.

Born in 1916, prematurely while his mother was at work in a mill, William Woodruff was one of four children. His parents, who married in 1904, had emigrated to Massachusetts but his mother's homesickness brought them back to Blackburn in 1914 and to hard slog in the cotton industry. His father volunteered for the Army. The fourth child, and second son, William, was sired during a "second honeymoon" on leave, from which his father returned to the front and to a near-fatal gassing at Ypres in late 1917: "a great runner ... he was one of the last to fall, one of the first to be picked up".

Now, in even greater contrast to his lively Irish wife, Woodruff's father "came home disillusioned. His experiences had shattered any desire he might have had for change and adventure ... Both body and mind were affected. For years he had a racking cough from the gassing". The Nab End of the book's title was not salvation but rather the humiliating lodgings the family found themselves in after a decade's hardship caused by the slump of the textile industry. Woodruff described the collapse:

"Post-war speculators borrowed money to buy stocks and shares which they promptly sold at a profit. Shares sold at £10 one day could fetch £15 the next. The more speculation, the higher their inflated values became. Without contributing a single constructive idea to the industry's welfare, the manufacturers and the money-spinners enriched themselves... while madness reigned, some manufacturers sold out at inflated prices and became wealthy country gentlemen. Others hung on, buying up businesses with borrowed money they could not possibly repay. Much of this money came from the banks. No matter what gains the factory owners made, my family's wages stayed at rock bottom. When the crash came in March 1920, and the industry collapsed, the banks found themselves the owners of much of the Lancashire textile industry and refused to pour good money after bad."

In his memoir, Woodruff recreates a teeming world of damp walls and precarious lavatories, hunger frequent and unemployment scarcely leavened by stitching mailbags in the kitchen; his descriptions of the pubs – brawls and all – visited by his parents recall those described by Anthony Burgess in Manchester of the same period.

One aunt took to haunting funerals – anybody's – before being thrown from her home, while a much-loved grandmother ended up in the workhouse. A new-born brother's coffin was destined for a pauper's grave ("he was never mentioned again"). One sister's scholarship hopes were dashed because the one item not included – smart shoes – was beyond their means (she joined the Salvation Army, and was about to marry a fellow member when bigamy was prevented by his wife's arrival at the ceremony).

On his first day at school Woodruff was hideously bullied, and he often fell asleep there, such was the toll taken by jobs elsewhere, including lunchtime delivery of food to his working parents. Only being stuck in an open window, and pulled out by his brother, saved Woodruff from juvenile burglary.

He left school at 13 and became a delivery boy, but his innate resilience was fostered by delight in Chaplin films and continual immersion in an encyclopaedia from Lifebuoy soap. That autodidactic impulse was encouraged by eccentric, well-meaning people he encountered in the library. At one point he even wrote to the Russian Trade Delegation to volunteer to work in their homeland; no reply forthcoming, he set off in 1933 for London and employment in a Bow foundry.

He was to describe that work, the city and his political ambitions vividly in his second volume of memoirs, Beyond Nab End (2003). An underground train advert alerted him to night school where, to his astonishment, one teacher, Miss Hesselthwaite, suggested university. He gained, with an LCC scholarship, a place at Oxford, in the Catholic Workers' College (later Plater College): "One of the best decisions I ever made." He evokes superbly a place in which many, for all their social ease, were as insecure as himself when it came to writing essays and learning to bat ideas with such historians as A.L. Rowse, G.D.H. Cole, Alexander B. Rodger and G.N. Clark.

Woodruff's pacifism was altered by travels in Germany, from which he returned on the very eve of the Second World War (he saw a Hamburg vessel turned round in mid-Channel). On a staircase in Christ Church, he met Kay Wright, a graduate at the Oxford County Agricultural Board. They married in 1941, by which time he was in the Army: "In the first five years of our married life we had five weeks together", and it was in Tunisia, in June 1943, that he learnt about the birth of a son, whom he did not see until December 1945 – after Greece, Crete and Italy (described in his 1969 novel Vessel of Sadness).

By then he was "devoid of political ambitions... the war had taught me to distrust political myths and grand panaceas. The small things in life had taken on a new intimacy; so had the heart". Back in Oxford, he gained a Bank of England fellowship. He then won a Fulbright Scholarship which took him to Harvard while writing The Rise of the British Rubber Industry during the Nineteenth Century (1958) – a scholarly work, in which a footnote points out that he could find only one contemporary article about contraceptives, and this was titled "Questionable Rubber Goods". By now he was Head of Economic History at the University of Melbourne in Australia and caring for his wife as she succumbed to cancer.

Woodruff married again in 1960, and joined the University of Florida in 1966, when he published Impact of Western Man, his richly informed account of Europe's effect upon the world (which expresses particular sympathy for the Aborigines – "perhaps in terms of human misery that tragedy reached its deepest depth in Australia"). His marshalling of facts makes plain such matters as the bulk of British investment in 1911 being not in the empire but in America (especially railroads); the changing post-Great War situation was explored in America's Impact on the World (1975).

He also taught in Princeton, Berlin, Oxford and Tokyo while based in Florida, whence a return to Blackburn in the late 1980s prompted the remarkable memoirs that bring a new resonance to many of the observations in his academic work; it haunted him that, whichever power is in the ascendant, "the relatively poor of the world are certain to become relatively poorer".

Christopher Hawtree

William Woodruff, economic historian and writer: born Blackburn, Lancashire 12 September 1916; married 1941 Katherine Wright (died 1959; two sons), married 1960 Helga Gaertner (four sons, one daughter); died Gainesville, Florida 23 September 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments