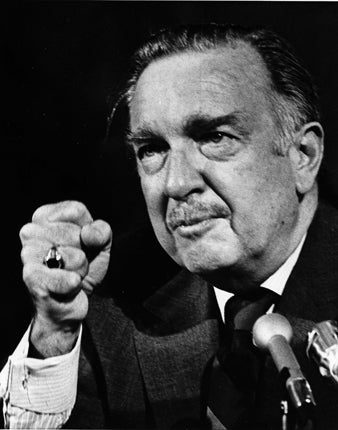

Walter Cronkite: Broadcaster who became America's conscience as well as the country's 'favourite uncle'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The predominance of CBS Evening News in the 1960s and '70s, against fierce network competition, was essentially due to the personality of its handsome anchorman, Walter Cronkite. His calm voice and reassuring presence seemed to offer security in an increasingly dangerous world. He was known as America's favourite uncle.

Like many top-notch journalists, Cronkite began his professional career reporting sport. After graduating from the University of Texas his first full-time job was as a radio sports announcer in Oklahoma City. In 1937, aged 21, he joined the United Press news agency, where he remained for 11 years. He became an intrepid war correspondent, covering the battle of the North Atlantic in 1942 and landing in North Africa with the invading Allied troops. He was among the first American newsmen to take part in Flying Fortress daylight bombing raids over Germany.

Walter Cronkite was then an ambitious, ginger-haired youngster, described by Harrison Salisbury, his boss at UP, as "the best operating hard news man in London". In 1943 Edward R. Murrow, who was then building up his outstanding team of CBS correspondents, spotted Cronkite's abilities and offered him twice his UP salary to come and join them. Salisbury persuaded the tight-fisted UP to provide a substantial rise and Cronkite stayed with the news agency.

He dropped with the 101st American Airborne Division in Holland, was with General Patton's Third Army in the Battle of the Bulge when it broke through the German encirclement at Bastogne, and reported the German surrender. In the latter stages of the war he re-established the United Press bureaux in Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg. As UP bureau chief in Brussels, he was the agency's chief correspondent at the Nuremberg war crimes trials.

With his charming wife Betsy he went in 1946 to Moscow for two years as the agency's chief correspondent. The difficulties were not limited to increasingly strained US/Soviet relations. The UP car was ancient and dilapidated, and during a particularly severe winter Cronkite sought permission to buy a new one (even the Russians were complaining about the old one's condition.) His superiors, however, suggested he get a bicycle.

Things like that undermine a foreign correspondent's confidence. Cronkite asked for a transfer home in 1948 and soon left UP. He lectured and contributed magazine articles before joining the CBS Washington Bureau, covering politics. From 1952 onwards he played a major role in coverage of the party conventions which nominated presidential candidates.

A decade later, he became anchorman of CBS Evening News, then a 15 minute programme but which expanded the following year to become the network's first half-hour-long national TV news show. It debuted with a Cronkite interview with President John F. Kennedy, and the combination of his authoritative presentation of the news of the day with the incisive analyses of his colleague Eric Sevareid made CBS the dominant TV news network of the era.

A list of Cronkite's assignments over three decades reads like a synopsis of mid-20th century world history: exclusive interviews with most major heads of government, including all US Presidents since Harry Truman; Watergate and the subsequent resignation of President Nixon; and the assassinations of Robert Kennedy, Dr Martin Luther King and – most unforgettably – of President Kennedy.

When word first came, around 1.30p.m. eastern time on 22 November 1963 that the President had been wounded, CBS broke into its programming and Cronkite, first in audio only and then on camera when a studio was ready, anchored the coverage. In a moment etched on the memories of those watching, Cronkite was handed a piece of paper from the Associated Press ticker. He put on his glasses, looked it over, and then took them off before informing his viewers: "From Dallas, Texas, the flash, apparently official: President Kennedy died at 1p.m. Central Standard Time, 2 o'clock Eastern Standard Time, some 38 minutes ago." He then paused briefly and put his glasses back, swallowing hard to keep his composure.

That day, however, he was only reporting history. With his coverage of the war in Vietnam, Cronkite may have changed history. He had grown increasingly sceptical about President Johnson's repeated assertions that America was winning the war, and in 1968 went to see for himself. His verdict was that the conflict had become a bloody stalemate and victory was not on the cards. The only rational way out, he declared, "will be to negotiate, not as victors, but as an honourable people who lived up to their pledge to defend democracy, and did the best they could."

Cronkite was Johnson's favourite newsman, and on hearing that judgement, the President turned to his aides and said, "It's all over." Cronkite, he knew, had more authority with the American people than any other broadcaster, and if Cronkite thought that the war was hopeless the American people would think so too. A few weeks later Johnson announced an end to the air and naval bombardment of most of Vietnam and that he would not seek another term. David Halberstam, the American media watcher, commented, "It was the first time in history that a war had been declared over by an anchorman."

But a change of administration did not soften Cronkite's views. As the deeply unpopular war continued under Nixon, and as CBS stepped up its coverage of the Watergate scandal, Republicans would accuse Cronkite of having a liberal bias. In an interview with Variety magazine, he admitted the offence, defining a liberal as "one who is not bound by doctrine or committed to a point of view in advance."

He took part, with Richard Dimbleby, in the first live TV exchange across the Atlantic, via Telstar. He became an authority on America's space programme, reporting Alan Shepard's first flight in 1961 and the Apollo 11 flight in 1969, when man landed on the moon. Recalling moments from that historic mission, which earned him an Emmy, Cronkite said, "I experienced a first in my life, too. I found myself on the air speechless."

In fact, his unflappability under pressure earned him the nickname of "Old Iron Pants." Cronkite received many awards for his journalistic achievements, most notably the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1981. The citation by Jimmy Carter praised him for "reporting and commenting on the events of the last two decades with a skill and insight which stands out in the news world."

Cronkite chaired his last edition of CBS Evening News on 6 March 1981. Almost 65, he was technically easing into retirement, with more time to enjoy sailing his 48-foot yacht the Wyntje – one of whose trips, from Chesapeake Bay down to Key West in Florida, resulted in the book South by Southeast (1983), with paintings by the artist Ray Ellis. The pair collaborated on two further sailing books, covering the waterways of America's Northeast Coast and its Pacific Coast.

But, as Cronkite himself put it on his valedictory statement on the Evening News, "Old anchormen don't fade away; they just keep coming back for more." Well into the 21st century he would provide special reports and commentaries on CBS, CNN, and National Public Radio. Later he was an outspoken critic of George W. Bush's 2003 invasion of Iraq, likening America's presence there to its bloody involvement in Vietnam a generation earlier.

Long before that, he had become a listed national institution. Typical was his performance in 2002 as the voice-over for the founding father Benjamin Franklin in all 40 episodes of an educational television cartoon called Liberty's Kids. During each one, he read historical news segments that ended with his old CBS anchorman sign-off, "And that's the way it is." No one of a certain age needed reminding who was speaking.

Leonard Miall

Walter Cronkite, broadcaster: born St Joseph, Missouri 4 November 1916; United Press reporter 1937-42; war correspondent 1942-45, foreign correspondent 1945-48; correspondent, CBS News Washington 1950, anchorman and managing editor CBS Evening News 1962-81; Presidential Medal of Freedom 1981; married 1940 Mary Elizabeth (Betsy) Maxwell (died 2005, two daughters, one son); died 17 July 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments