Victor Kiernan: Marxist historian, writer and linguist who challenged the tenets of Imperialism

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Victor Kiernan, professor emeritus of Modern History at Edinburgh University, was an erudite Marxist historian with wide-ranging interests that spanned virtually every continent. His passion for history and radical politics, classical languages and world literature was evenly divided.

His interest in languages was developed at home in south Manchester. His father worked for the Manchester Ship Canal as a translator of Spanish and Portuguese and young Victor picked these up even before getting a scholarship to Manchester Grammar School, where he learnt Greek and Latin. His early love for Horace (his favourite poet) resulted in a later book. He went on to Trinity College, Cambridge where he studied History, imbibed the prevalent anti-fascist outlook and like many others joined the British Communist Party.

Unlike some of his distinguished colleagues (Eric Hobsbawm, Christopher Hill, Rodney Hilton, Edward Thompson) in the Communist Party Historians Group founded in 1946, Kiernan wrote a great deal on countries and cultures far removed from Britain and Europe. A flavour of the man is evident from the opening paragraphs of a 1989 essay on the monarchy published in the New Left Review:

In China an immemorial throne crumbled in 1911; India put its Rajas and Nawabs in the wastepaper-basket as soon as it gained independence in 1947; in Ethiopia the Lion of Judah has lately ceased to roar. Monarchy survives in odd corners of Asia; and in Japan and Britain. In Asia sainthood has often been hereditary, and can yield a comfortable income to remote descendants of holy men; in Europe hereditary monarchy had something of the same numinous character. In both cases a dim sense of an invisible flow of vital forces from generation to generation, linking together the endless series, has been at work. Very primitive feeling may lurk under civilized waistcoats.

Notions derived from age-old magic helped Europe's 'absolute monarchs' to convince taxpayers that a country's entire welfare, even survival, was bound up with its God-sent ruler's. Mughal emperors appeared daily on their balcony so that their subjects could see them and feel satisfied that all was well. Rajput princes would ride in a daily cavalcade through their small capitals, for the same reason. Any practical relevance of the crown to public well-being has long since vanished, but somehow in Britain the existence of a Royal Family seems to convince people in some subliminal way that everything is going to turn out all right for them... Things of today may have ancient roots; on the other hand antiques are often forgeries, and Royal sentiment in Britain today is largely an artificial product.

Kiernan's knowledge of India was first-hand. He was there from 1938-46, establishing contacts and organising study-circles with local Communists and teaching at Aitchison (formerly Chiefs) College, an institution created to educate the Indian nobility along the lines suggested by the late Lord Macaulay. What the students (mostly wooden-headed wastrels) made of Kiernan has never been revealed, but one or two of the better ones did later embrace radical ideas. It would be nice to think that he was responsible: it is hard to imagine who else it could have been. The experience taught him a great deal about imperialism and in a set of stunningly well-written books he wrote a great deal on the origins and development of the American Empire, the Spanish colonisation of South America and on other European empires.

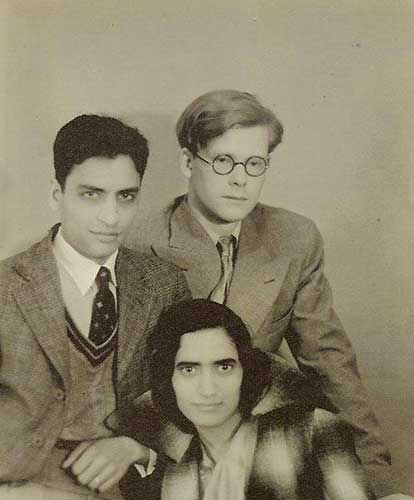

He was by now fluent in Persian and Urdu and had met Iqbal and the young Faiz, two of the greatest poets produced by Northern India. Kiernan translated both of them into English, which played no small part in helping to enlarge their audience at a time when imperial languages were totally dominant. His interpretation of Shakespeare is much underrated but were it put on course lists it would be a healthy antidote to the embalming.

He had married the dancer and theatrical activist Shanta Gandhi in 1938 in Bombay, but they split up before Kiernan left India in 1946. Almost forty years later he married Heather Massey. When I met him soon afterwards he confessed that she had rejuvenated him intellectually. Kiernan's subsequent writings confirmed this view.

Throughout his life he stubbornly adhered to Marxist ideas, but without a trace of rigidity or sullenness. He was not one to pander to the latest fashions and despised the post-modernist wave that swept the academy in the 80s and 90s, rejecting history in favour of trivia. Angered by triumphalist mainstream commentaries proclaiming the virtues of capitalism he wrote a sharp rebuttal. "Modern Capitalism and Its Shepherds" was published once again in the New Left Review in October 1990:

Merchant capital, usurer capital, have been ubiquitous, but they have not by themselves brought about any decisive alteration of the world. It is industrial capital that has led to revolutionary change, and been the highroad to a scientific technology that has transformed agriculture as well as industry, society as well as economy. Industrial capitalism peeped out here and there before the nineteenth century, but on any considerable scale it seems to have been rejected like an alien graft, as something too unnatural to spread far. It has been a strange aberration on the human path, an abrupt mutation. Forces outside economic life were needed to establish it; only very complex, exceptional conditions could engender, or keep alive, the entrepreneurial spirit. There have always been much easier ways of making money than long-term industrial investment, the hard grind of running a factory. J.P. Morgan preferred to sit in a back parlour on Wall Street smoking cigars and playing solitaire, while money flowed towards him. The English, first to discover the industrial highroad, were soon deserting it for similar parlours in the City, or looking for byways, short cuts and colonial Eldorados.

The current crisis would not have surprised him at all. Fictive capital, I can hear him saying, has no future.

Tariq Ali

Victor Gordon Kiernan, historian and writer: born Manchester 4 September 1913; Married 1938 Shanta Gandhi (marriage dissolved 1946), 1984 Heather Massey; died 17 February 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments