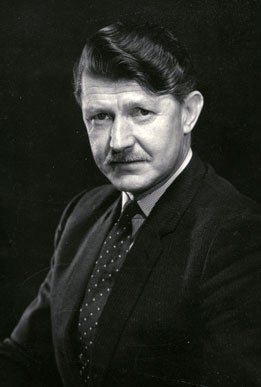

Thomas Tuohy: Windscale manager who doused the flames of the 1957 fire

On 10 October 1957, at the age of 39, Thomas Tuohy was deputy to the general manager at the Windscale and Calder works of the Ministry of Supply (now known as Sellafield) when one of the "piles" – primitive nuclear reactors – making plutonium for Britain's first atomic bombs overheated. His boss phoned him at home where he was nursing a family sick with flu: "Come at once. Pile number one is on fire." Tuohy told his wife and two children, living about a mile from the works, to stay indoors and keep all the windows closed.

At the factory he flouted standing orders by discarding his radiation recording badge, so that no one could tell him that he had exceeded permitted radiation dose limits and lay him off work. He went immediately to the top of the 80ft pile and peered down vertical inspection holes in the concrete pile cap into the graphite core. He could see the bright glow from the fire near the pile's discharge face.

Over the next few hours, he repeated his inspections, watching the fire grow. He reckoned that about 120 of the horizontal fuel channels filled with uranium slugs being transmuted into plutonium were ablaze. His workers were sweating away with steel rods, trying to shove the burning fuel cartridges, distorted by heat, out of the conflagration.

From the colour of the flames, Tom Tuohy estimated that the fire must be approaching the melting point of steel. He continued his inspections throughout the night. Around dawn, he had all the available carbon dioxide gas pumped into the core to try to quell the inferno, but to no dramatic effect. There were signs, however, that the fire was abating.

Then a new fear arose. The thick concrete biological shield that was protecting Tuohy and the rest of the world from the core's intense radiation might begin to collapse under the heat.

Earlier, Tuohy had agreed with his peers on site that if it came to the worst, water must be used to drown the fire. It raised serious risks of exacerbating the damage – for example, by creating an explosive mixture of water, gas and air that might blow the pile apart. But time was running out. Tuohy told his fire chief where to position the hoses, two feet above the fire. He remained in the pile while the water began to flow, gently at first.

Initially, nothing happened, so Tuohy switched off the blowers that were blasting gale-force cooling air through the pile, keeping the temperature tolerable for the fire-fighters but also fanning the flames. It did the trick and they watched the fire die.

Five hours later, Tuohy was reporting to his boss, at home with flu, that the fire had been extinguished. Nevertheless they kept water flowing for another 30 hours. The pile structure, so sternly tested, survives to this day.

Tuohy returned to his own sick family at Beckermet, within sight of the pile. Half-a-century later, shortly before he emigrated to Australia, Tuohy helped make a BBC documentary on the nuclear accident (Windscale: Britain's biggest nuclear disaster). The Windscale fire was to have a profound influence on Britain's approach to nuclear health and safety, inspiring the creation of a nuclear health and safety executive headed by a Chief Nuclear Inspector.

Born in England of Irish parents, Tuohy obtained his BSc from Reading University and spent the Second World War years as a chemist in Royal Ordnance factories, before joining the new nuclear project in 1946, as manager of health physics at the Springfields factory near Preston, where fuel for the piles was made. In 1949 he moved to Windscale in Cumbria to do the same job.

In 1951 Tuohy led the team that poured Windscale's first billet of pure plutonium metal. He had distinguished himself the previous year when pile number one was nearing completion and Harwell calculated that its productivity would be much lower than previously thought. One last-minute modification was to trim fins on the 70,000 fuel cans that enclosed the uranium slugs. It would have taken too long to unload the pile and take the slugs back to the workshop. So Tuohy set up a facility on the discharge hoist of the pile itself. Cartridges emerged at one point, went down a line that clipped 1/16 of an inch off each of the fins, and returned them to the pile. Tuohy's system clipped about one million fins in about three weeks.

Tuohy took charge of operations when the first billet of home-made plutonium was poured at Windscale in March 1951. It was not the first pure plutonium to be seen in Britain – that had been at Harwell three months earlier, using Canadian material. Tuohy recalled how the lid of the crucible in which Windscale's newly minted metal was melted had stuck, so he swiped it with a steel rod. All operations involving plutonium were carried out in glove boxes to protect operators from alpha radiation. It greatly complicated operations but Tuohy once commented that the metal was nothing like so difficult to work with as polonium-210, also made at Windscale in the early years of atom bombs.

In February 1964 the Windscale factory received a severe shock. A new defence white paper asserted that Britain now had adequate stockpiles of fissile materials for its foreseeable bomb-making needs. The nation was collaborating once more with the Americans and using some US designs. Production of weapons-grade plutonium at Windscale was to cease. Con Allday, who later would become chairman of British Nuclear Fuels, was to carry the message to Tuohy, by now Windscale's general manager. Henceforth his annual budget would be a mere £2m.

Tuohy faced up to the new challenge with customary vigour. While top management sought new civilian markets for its nuclear expertise, he embarked on a rigorous programme of cost-cutting. His undoubted success in this activity would have unfortunate repercussions in the 1970s.

In 1970 the government created British Nuclear Fuels (BNFL) with Sir John Hill as chairman and a trio of managing directors. It was not a comfortable arrangement. Tuohy was made managing director responsible for production, running factories at Windscale, Springfields and Capenhurst.

In 1971 BNFL became the UK shareholder in an ambitious tripartite project with Holland and West Germany, called Urenco. Urenco was to develop and exploit a new technology for enriching the fissile uranium content of nuclear fuel for reactors. It was called the lightweight ultracentrifuge and had been under development secretly in all three countries. The idea was that by pooling ideas the three could make a big advance in a novel technology, in competition with the current US domination of the enrichment market. Collaboration was not easy, however, for each nation saw itself in pole position.

Tuohy represented the UK in various part-time capacities until 1973, when he was appointed Urenco's managing director. His appointment solved problems at BNFL but was inappropriate for a situation that called for patient diplomacy. From the outset he left no one in doubt that he was going to bang heads together and force through radical changes. He enlivened Urenco's staff Christmas dinner that year with his own summary – in verse – of the project's hapless history so far.

Even so, he managed to persuade the partners to agree to construct two (not three) demonstration plants, in England and Holland, to kick-start the venture. But they were still far from pooling their technical effort. Nevertheless, in 1974 Urenco produced its first business plan, looking 10 years ahead.

But the forthright, decisive style of Tuohy's direction was ill-accepted by the fledgling company. While his ideas were forcing the partners to face up to their own weaknesses, Tuohy's bluntness was alienating him from his shareholders. They proposed a new corporate structure which he saw as completely unacceptable because of the power it gave the shareholders over his decision-making. He resigned in October 1974, still only 54. It would be the end of his career in nuclear energy.

David Fishlock

Thomas Tuohy, chemist: born Newcastle upon Tyne 7 November 1917; manager, Health Physics, Springfields Nuclear Fuel Plant, Department of Atomic Energy 1946, works manager 1952-54; manager, Health Physics, Windscale Plutonium Plant 1949, manager, Plutonium Piles and Metal Plant 1950-52, works manager 1954-57, deputy general manager 1957-58, general manager 1958-64; managing director, Production Group, UK Atomic Energy Authority 1964-71; CBE 1969; managing director, British Nuclear Fuels Ltd 1971-73; managing director, Urenco 1973-74; three times married (one son, one daughter); died Newcastle, New South Wales 12 March 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments