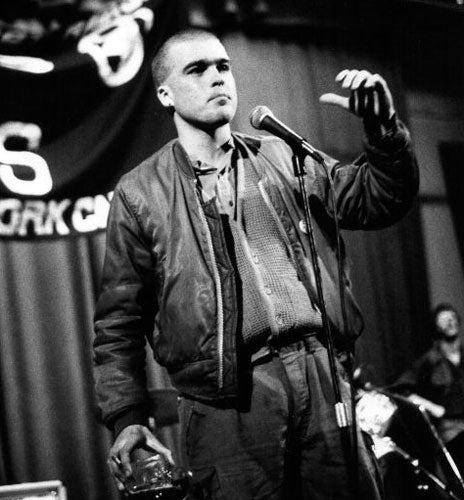

Steven Wells: Journalist celebrated for his 'ranting poetry' and iconoclastic pop writing

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Few cancer memoirs have happy endings. Nine days before his death from enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma, the British journalist and pop, sport and political polemicist Steven Wells – "Swells" to all who knew him personally – wrote his last column for the Philadelphia Weekly. In it, he struggled to sum up his life's work as a socialist and moralist of unbending principle, tempered, but never contradicted, by an outrageous gift for tragicomic fantasy and verbal fireworks.

"I speak as someone whose greatest craving at this exact moment is not world peace and universal democracy or a rational and global redistribution of wealth," he wrote, "but a can of ice cold ginger ale." In extremis, the "idiot who has polished his image as an existentialist, atheist hard-man and anti-mope, forever sneering at the tribes who wallow in self-pity" had little to savour but the black irony of composing himself for the inevitable. How to account in the final reckoning for those tribes "composed entirely of the white male urban middle-classes who are convinced that (as the most affluent and pampered human beings who have ever walked the planet) theirs is a story worth hearing"? You could, he wrote, "blame this fallacy on poor education, cultural deterioration, or simple moral decline.

"Me? I blame it on sunshine. I blame it on the moonlight. I blame it on the boogie."

A day after Wells' death, the singer who had provided his last, blackest joke was himself to die. As a writer, performer and in person, such was the force of Swells' wit and intelligence, his gleeful gift for provocation and satire, the humane warmth behind his posture of almost insane aggression, that for hundreds upon hundreds of his fans and friends who continue to post tributes and memories online, his passing was not to be eclipsed as an event by that of arguably the most famous man in the world. Wells can have few, if any, contemporaries in British journalism whose death would provoke so much shock, dismay and genuine grief.

The curriculum vitae of the man who performed as the "ranting poet" Seething Wells and also wrote under the pseudonym Susan Williams (which is how I innocently encountered his typewritten, posted-in copy while editing reviews in the New Musical Express in 1983), gives but the barest impression of the impact he had. Born in Swindon, the son of a lifelong socialist finance director – the second half of that equation being an occasion for some teasing by his music press colleagues exasperated by Swells' unceasing class war on every front, from the sound of a Belle and Sebastian record to the cut of Johnny Rotten's trousers – he moved to Bradford as a child. With the arrival of the punk movement in the late 1970s and its ready-made target in the recently elected Thatcher government, the some-time factory worker, bus conductor and fully paid-up member of the Socialist Workers Party became a star of a grassroots scene of angry, radical rock bands and, in his case, ranting poets, and the fanzines that bush-telegraphed this small but intensely vibrant world.

Proudly provincial but a scourge of professional northerners and soft southerners alike (being perhaps a bit of both back then), Swells followed his ambition to London where, retiring Seething Wells, ranting poet, he swiftly established himself as the funniest writer on the New Musical Express, then selling well over 130,000 copies a week and, like John Peel's radio show, highly influential in an "alternative" UK music scene which was already quite distinct from the mainstream.

Adopting the confrontational, sacred-cow-slaughtering tactics of his NME predecessor Julie Burchill (or Jusbo Bitchkill, as he affectionately called her), Swells was even more entertaining, and often penetrating, when his gaze redirected itself away from his pet bands and pet hates to the big beasts of pop culture, whether grilling Mary Whitehouse or, in answer to Mike Oldfield asking him if he was a member of the Mile High Club, replying, "Does wanking count?"

Briefly holding down a spot on the BBC2 rock show The Old Grey Whistle Test until he was fired for an over-the-top joke at the expense of the late John Lennon, in the Nineties he diversified into radio as a co-writer with NME's fellow mirth-maker, David Quantick, for On the Hour (1991-92) and The Day Today (1994). Without any technical training, Swells also turned his terrifying energies to co-directing music videos, including The Manic Street Preachers' "Little Baby Nothing", which crystallises his philosophy of selling a roundhead message with surreally cavalier panache.

As a tactic, it was often misunderstood, and after publishing his British gonzo novel Tits-Out Teenage Terror Totty in 1999, he celebrated turning 40 by adding football to his portfolio of topics guaranteed to find a wide readership split between irate literalists and devotees who got the joke when he challenged some deeply held received opinions, such as that the referee shouldn't get above his humble station. As editor of the football monthly FourFourTwo I had the intense pleasure of commissioning Swells to write about the Millwall-West Ham derby, football hooligans-turned-memoirists and soccer in America. It was while writing that piece that he met the academic sociologist Katharine W. Jones, a professor at Philadelphia University; now resident in the City of Brotherly Love, he married her.

The Bush years were a gift to a writer who had been mocking "USAians" for half his lifetime, but married bliss spent observing the absurdities of American spectator sports was derailed by his diagnosis with Hodgkin's lymphoma in 2006. Barely had he beaten that than he was diagnosed in January with the cancer that was to kill him. His stories for the Philadelphia Weekly on the illnesses and his ordeals in the healthcare system can stand comparison with the cancer memoirs of Simon Gray and John Diamond, their frank and savage wit a testament to a writer and man who never lost his rage to live.

Mat Snow

Swells, I always thought you'd pull through, writes John Baine (Attila the Stockbroker). I'd read "The English Patient" – your brilliant, witty, moving piece about your simultaneous battle with cancer and the US healthcare system – in the Philadelphia Weekly, swapped emails where you sounded as, well, Swellslike as ever, and thought: you'll make it. This is one roaring, iconoclastic, larger-than-life, indestructible, stupidly clever, logically illogical, everything-demolishing mouth monster who won't be demolished himself by something as mundane as cancer. But no. Seething Wells is dead. "Swells" and "dead" in the same sentence...

Despite his long "career" (he hated that word!) in music journalism, Swells was first and foremost a poet, who I first heard in 1981. I'd christened myself Attila the Stockbroker and had started getting up on stage performing political poems between bands. He wrote to me, enclosing his fanzine Molotov Comics, saying he was doing the same in Bradford, and so were some friends of his including Joolz and Slade the Leveller, from a then unknown band, New Model Army. He called it "ranting poetry" and from the moment I heard the phrase, so did I.

Our first meeting was performing on the back of a lorry at a Right to Work demonstration in London in November 1981. Coincidentally, Paul Weller was headlining a poetry event at the Young Vic theatre that night and I persuaded Swells to come and "crash" it with me and try and blag a few minutes. The organiser Michael Horovitz, bless him, gave us 10 between us and the audience loved it. So did Weller: two weeks later we were supporting the Jam at Hammersmith Odeon. The NME editor Neil Spencer was there to review the gig and sent budding writer and soon-to- be Redskins leader Chris Moore to do a big review of us at another gig a few weeks later. A music press "ranting poetry" fad was born. And so was a pugnacious punk-poetry partnership.

Swells and I did an EP together, "Rough Raw & Ranting", which hit the indie charts, then a book for Unwins, The Rising Sons of Ranting Verse and for the next few years we saw a hell of a lot of each other. We gigged together, wrestled, drank, argued and shouted together, watched bands together, went on demos together. But underneath the roaring exterior (and many people will be astonished by this) Swells never really enjoyed being on stage: many was the time I remember him throwing up before we tackled an audience. I guess it was this, plus his realisation that he could reach many more people writing for papers like the NME, that made him make the transition, first to Susan Williams, social surrealist feminist rock critic (many fell for it!) and then to the Steven Wells loved (by bands he liked) loathed (by bands he didn't) and feared (by bands who didn't know whether he was going to like or loathe them).

We kept in touch as the years went by. I'd take the piss out of him for choosing nerdy, trainspotteresque, behind-the-scenes music hackdom as the vehicle for his scattergun obliterations of everything Middle England held dear rather than getting on stage and doing it in front of a live audience. He'd take the piss out of me for stubbornly carrying on being a ranting poet despite the fact that the entire collected ranks of nerdy music hackdom he hung around with thought ranting poetry was finished and rubbish. We'd agree to differ. Then we'd smile, get drunk and wrestle with each other. And slag off Morrissey.

In the Nineties I tried to coax him out of retirement and instigate the Seething Wells Comeback. I got as far as booking him for a gig at the performance poetry series I was running near Brighton – but he phoned a couple of days before to cancel. So I gave up that idea and just enjoyed his demolitions of bad bands, bad football and bad politics in all the publications that would have him. (Plus the humanity, insight and above all the supreme intelligence which imbued all his writing – but I never told him that bit.)

He moved to the US to be with Katharine, and our occasional contacts became more occasional. Then, one day in 2006 I thought, "I wonder what Swells is doing now?" Googled him. To my shock the first thing I found was the "English Patient" article, and I got back in touch and stayed so to the end. A month ago I was congratulating him on a great piece on the corporate hijacking of football and he was doing the same to me about the football poems on my website (maybe we were mellowing in our old age). Last Tuesday I emailed him a poem, "Dad Rock Antidote Manifesto" which I thought he'd like. Same old Swells. He was up for the battle, that's for sure. Celebrations of his life will be held in Bradford on 13 September and the Albany in Deptford on 4 December.

Steven Wells, journalist, author, broadcaster, video director: born Swindon 10 May 1960; married Katharine W. Jones; died Philadelphia 23 June 2009.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments