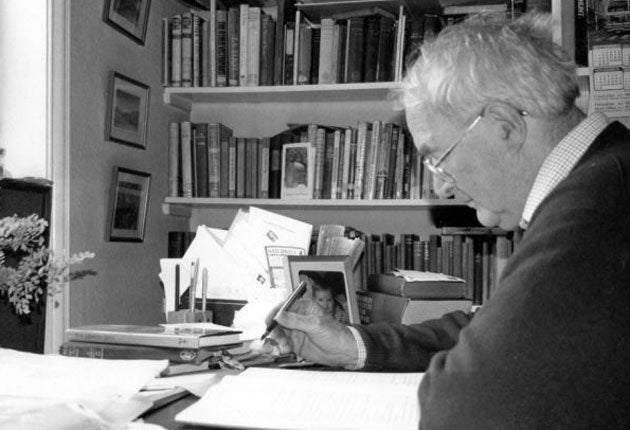

Stanley Middleton: Booker Prize-winning novelist whose works dissected the mores of Middle England

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Stanley Middleton, who has died at the age of 89, was an award-winning novelist with a particular gift for delving beneath the veneer of Middle England to reveal, in the sparest of prose, inner character and inner truths.

The skill and insights he brought to dissecting the private depths of the middle class earned him descriptions such as the "connoisseur of the mundane" and, indeed, "the Chekhov of suburbia". So all-seeing were his observational powers that he was even referred to as "God's spy".

Although in more recent times his work has gone out of fashion, he has retained a circle of admirers who regard him as, if not quite godlike, certainly a hugely under-rated talent. His novels are not known for incident: indeed, it has been said of them that, for the most part, nothing happens. Middleton enthusiasts might reply that the art lies in the way that nothing happens.

His Booker Prize came in 1974 for his novel Holiday, in which an education lecturer visiting a seaside resort is affected by themes such as death, marriage and separation. Middleton shared the prize with the South African Nobel laureate Nadine Gordimer.

He was noted not just for quality, but also for quantity and consistency: for 44 years he produced a book annually. Some readers argued that his work did not change enough over the decades; others held that in fact he subtly traced developments in society.

His talent for finding something special in the commonplace was deftly captured by the critic Isabel Quigly. "Meticulously observant, the writing pared down to essentials but the contents full of detail," she wrote of Middleton's work. "His books have the ordinariness, even the social dullness, of everyday life. But with insights, and a peculiar artistry, social dullness is transmuted by amazing realism, exactness turned into beauty of a sort."

Almost all of Middleton's life was spent in Nottingham, where practically all of his books were based: he retained a lifelong fascination for what were described as "middle-class, middle-aged, Midland dwellers". He summed up his aims as "not only to tell an interesting story, but to demonstrate the complexity of human character and motive." Enlarging on this he added: "Unless a novel is complex, memorable, capable of holding a reader and moving him deeply, I've not much time for it."

A key early influence was another Nottingham writer, D H Lawrence. Middleton said that Lawrence "opened my eyes to the possibility that a major author could write about the sort of life I saw around me, using my own dialect and describing places that I had seen with my own eyes."

Born in Nottingham in August 1919, Middleton was the son of a railway guard. He attended High Pavement Grammar School then went on to train locally as a teacher. His studies were interrupted by the Second World War, in which he served in the Royal Artillery and in the Army Educational Corps. He drew on his experiences with the Corps in India for one book, Her Three Wise Men (2008).

After taking his diploma at the University College of Nottingham he returned to High Pavement school. He taught there from 1947 until 1981, spending 23 years as head of the English department. A number of his pupils remember him as an exceptional teacher, one recalling that, "his gentle, amiable character was loved and respected by all." Another paid tribute to both his teaching and his throwing arm, describing him as "the only master who could hold the full attention of his class – he also excelled with a blackboard duster at twenty feet."

Although he was aged 38 when he published his first novel, A Short Answer, he was thereafter a prolific writer. He was also a deft watercolourist and highly musical, playing the organ in local churches. He incorporated music into a number of his works, which are often regarded as among his best.

Middleton himself shared this assessment, saying that these were the works which most excited and satisfied him. He declared: "I sometimes think that, if I had any real choice in the matter, I'd have been a composer. But I wasn't, alas, good enough."

He and many readers considered his best work to be not Holiday but the 1960 novel Harris's Requiem, which was set in the thriving Nottingham classical musical scene. V S Naipaul enthused: "He has succeeded in doing a difficult thing – he has made a composer his hero, and made him wholly credible. Eventually we feel we know his world; and it is a complete world.

"He writes carefully, but his touch is astonishingly assured. One rarely reads dialogue as good as Mr Middleton's; it makes his characters instantly alive."

Another critic was lyrical in his praise, saying that the characters in the book "weave in and out of each others' lives in a novel that is not so much written as delicately scored."

With characteristic modesty, Middleton turned down an MBE in 1979 on the grounds that he had not done enough to deserve it. In 1982 he became a visiting fellow at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, and in 1998 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. He held honorary degrees from the Open University and Nottingham University.

Nottingham honoured him with the publication of Stanley Middleton at Eighty (1999), a collection of his work together with essays by A S Byatt, Philip Callow and John Lucas. Professor Lucas wrote of him: "His prose, although straightforward, was capable of great poetic resonance."

But although Nottingham revered him, the wider literary world came to neglect him: he was not the first or the last Booker winner to fade from prominence. In 2006, when The Sunday Times submitted a chapter from Holiday to publishers and agents, 20 of 21 responded with rejections. His reaction to this was to grumble: "People don't seem to know what a good novel is nowadays."

On another occasion he said that it was galling to find that critics "usually dump my novels as 'dashed down without care'." A friend and protégé added that "he always (resignedly) resented being dismissed as a mere provincial realist." A year ago, another devotee lamented: "I'm a huge Stanley Middleton fan, and had begun to suspect that I was the only one left."

Middleton himself provided a modest epitaph for himself. "I guess I seem old-fashioned to modern critics," he wrote to a correspondent. "But fashion plays its part, and perhaps my time and method will come round again."

David McKittrick

Stanley Middleton, novelist and teacher: born Bulwell, Nottingham 1 August 1919; married 1951 Margaret Welch (two daughters); died Nottingham 25 July 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments