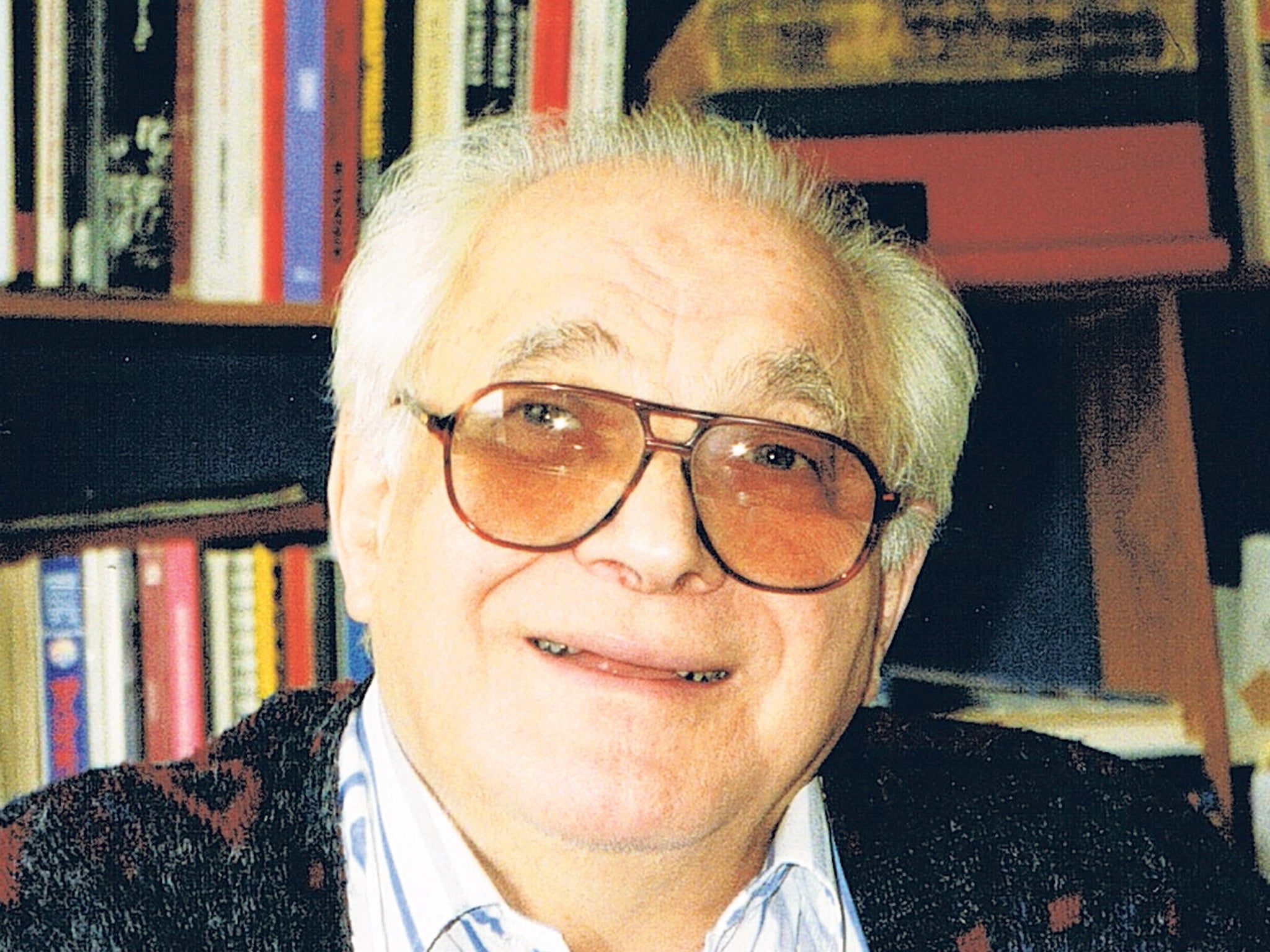

Stanley Forman: Film producer and distributor who advanced the socialist cause for 50 years

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Stanley Forman was a major figure in British left-wing cinema; for several decades he distributed films from socialist countries. He and I first made contact in 1960 after a film I'd hired for a CND meeting turned out to be third-rate propaganda. I wrote back saying so. Fourteen years later we were making a film together.

Stanley Forman was born in East London in 1921 to a family who had escaped from poverty and pogroms in Russian-controlled Poland. His mother was illiterate, his father a successful tailor with his own business. As a youth he rejected Judaism, though not Jewish culture. "I love being Jewish, but I just never warmed to religion," he said. "I took great exception to one of the prayers I had to say which translates as, 'I thank thee God for not having made me a woman'. I was 13 when I abandoned Judaism and began to think about social justice."

As a 15-year-old communist he wanted to join the crowds in Cable Street demonstrating against Mosley's fascists. But he obeyed his mother and stayed indoors – "She had this great fear that being a communist meant you were going to get clonked over the head by a policeman on a horse." Convinced that in Marxism he would find the "Schussel" (the Key), he spent hours at the Marx Memorial Library.

His first job was at the German Jewish Aid Committee in Bloomsbury but in 1939, despite having contact with refugees from the Nazis, he followed the Communist Party line that Hitler's invasion of Poland was just another imperialist war, " I bloody well accepted it. I just accepted it." While waiting for his call-up papers he became an organiser for the Communist Party in Leeds.

On D-Day 1944 he was in the Essex Yeomanry aboard a TLC (tank landing craft) going ashore in France, and he fought with them as they advanced through the Netherlands and Germany. By 1946 he was a warrant officer, running the Field Security Service's de-Nazification programme in Kiel. As soon as the War Office became aware of his politics he was demobbed and returned to Leeds, where he married a fellow communist, Hilda Davies.

Party connections helped him get office jobs with the British-Soviet Society, the Civil Service Trade Union and in the film industry. In 1950, with Ivor Montagu (who had worked with Hitchcock and Michael Balcon), Daily Worker journalist Bill Wainwright and composer Alan Bush £500 was raised and Plato Films set up to distribute films from the embassies of the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe and China.

Most of Plato's early offerings were, as Forman put it, "pathetic". But for documentaries from socialist countries they were the only show in town. The library grew in importance after the donation of British labour movement films such as Worker's Newsreels and Against the Means Test, collected in the 1930s by Montagu and Sidney Bernstein (founder of Granada TV).

In 1951 Forman visited Russia and enjoyed every minute of it. "But of course you don't get taken to the gulags... I've never been taken for a ride, except in the big one with a lot of other good people. I'm talking about the Stalin ride." He stayed in the Communist Party after Nikita Khrushchev revealed some of Stalin's crimes and the Soviet Union crushed the 1956 Hungarian revolt.

Plato survived by posting 16mm copies to a motley collection of film societies, left-wing bodies and language schools. In 1959 the company screened an East German documentary, Operation Teutonic Sword, to an invited audience at the National Film Theatre. The film accused General Hans Speidel, the commander of Nato's ground forces, of being a Nazi war criminal and being involved in the assassination of King Alexander of Yugoslavia.

Speidel responded with a writ for libel. Forman was warned that his home and Plato Films were at risk. The film's producers, the East German government, paid the defence costs for three years of wrangling that went as high as the House of Lords. "We had to come to a sort of draw, a reluctant decision that we wouldn't show the film to the public at all and that every side would pay its own costs," Forman recalled. His house was safe and he formed a new company, Educational and Television Films.

He spent weeks of his life in Russia and East Germany attending political gatherings and watching turgidly predictable documentaries, waiting for the occasional jewel to show up. In East Germany he had a secret personal life and two daughters, Sarah and Flora. In London, he took pride in his wife Hilda's management of an NHS general practice and was similarly proud that his son David became an internationally respected cancer research specialist.

By the 1970s ETV's film-hire bookings were drying up and it became increasingly dependent on the sale to television of material dealing with subjects such as Vietnamese life under American bombs or the Soviet space programme. I made use of their collections for several films and in 1974 Stanley asked me if I would join him and direct a film about the life and murder of the Chilean folk-singer Victor Jara. I was wary of making the film with such a convinced communist; none the less, Compañero: Victor Jara of Chile, in which Jara's widow Joan describes her experiences during General Pinochet's 1973 coup – a tragic love story rooted in 20th century politics – made us lifelong friends.

The sale of archive material to series like Horizon and People's Century enabled ETV to last longer than the socialist countries who had made the films. In 1994, I persuaded Channel 4 and Stanley that a film about his life and work could be a revealing undertaking. We made it, but not without crossed swords. Most often they centred on what I saw as his refusal to own up to the enormity of Stalin's crimes. On camera he told me that I was his dear friend, "but not a dear comrade" and apologised for failing to convey "the spirit of the times".

Stanley's wife, Hilda, died in 2008. By then her husband was in a care home and his films in the National Film Archive.

Stanley Forman, film distributor and producer: born London 26 December 1921; married Hilda Davies (died 2008): died Harrogate 7 February 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments