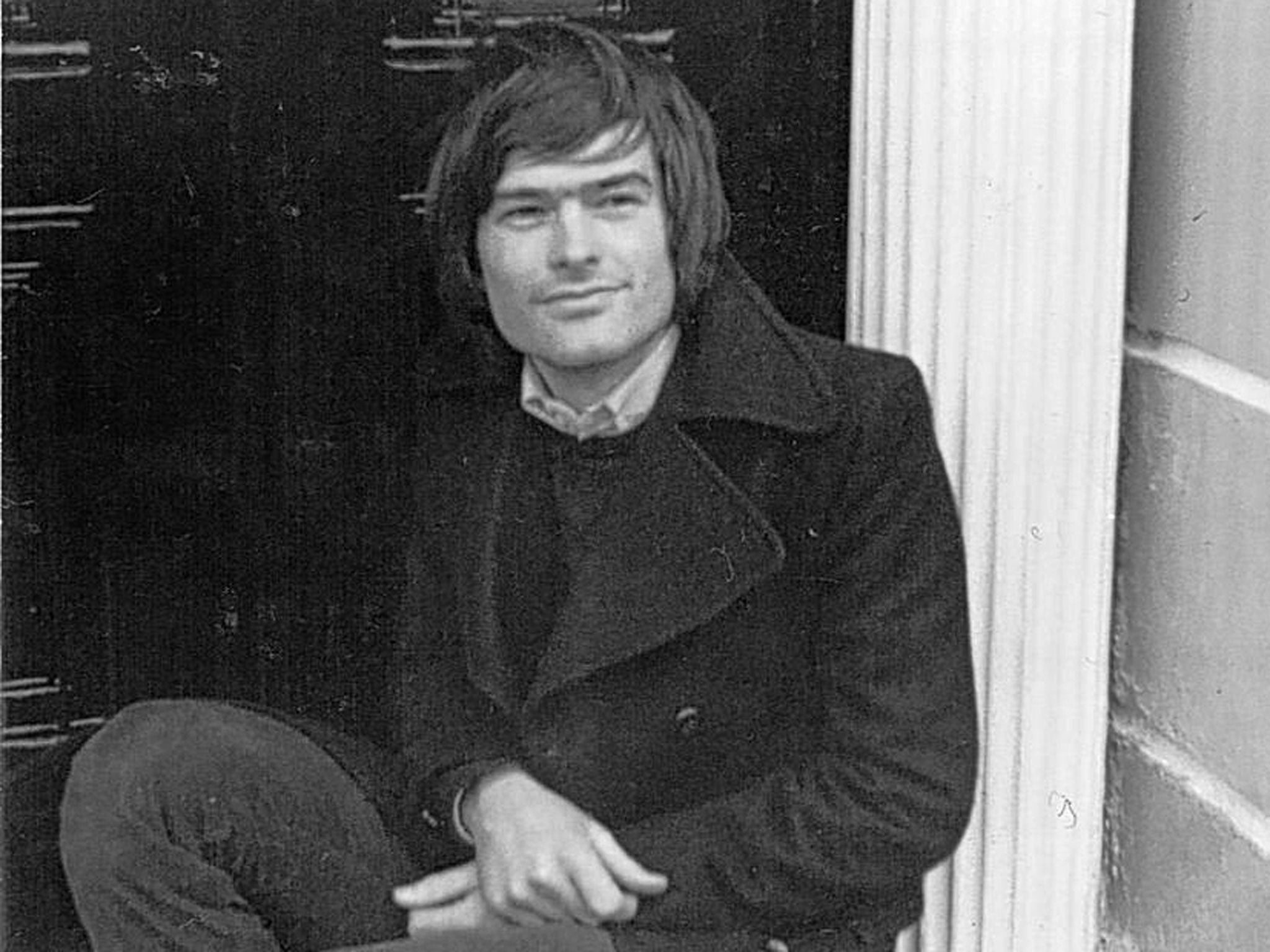

Sir Nicholas Browne: Britain's chargé d'affaires in Tehran who faced an angry mob following the fatwa issued on Salman Rushdie

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sir Nicholas Browne was targeted by an angry mob in Tehran in 1989 after the Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa calling for the killing of the author Salman Rushdie over his book The Satanic Verses. Browne, then the British chargé d'affaires, had to retreat with his staff to the inner rooms of the British embassy as the crowd, variously estimated at between two and ten thousand, hurled debris that smashed the building's windows, only a few yards away from the imposing black-painted outer gates adorned with the Royal Crest. He was forced to call for police protection, though no one was hurt.

The attack came in February that year, only a month after Browne's arrival at the newly re-opened embassy. There had been a rupture in relations since the Revolutionary Guards stormed it in 1980 just after Khomeini had come to power in 1979. Browne, a fluent Persian (Farsi) speaker, was designated chargé d'affaires, since relations were still so frosty as to rule out the title of ambassador. By 1989 he was an acknowledged expert on Iranian affairs, and the secret report he had written a decade before into how the Islamic revolution took Britain by surprise had become required reading in the Foreign Office.

Browne's devastating conclusion in the 90-page report that took a year's research in 1979 was not to become public until 2010. Britain, he wrote, had been so intent in the 1970s on her economic need to sell arms abroad, including to the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, that her Tehran envoys failed to explore beyond the glitter and flattery of audiences before the soon-to-be-overturned Peacock Throne.

The British embassy had "overstated the personal popularity of the Shah ... knew too little about the activities of Khomeini's followers ... saw no need to report on the financial activities of leading Iranians ... [and] failed to foresee that the pace of events would become so fast." Browne had been "on loan" from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office to the Cabinet Office, when he led the investigation, a rare event which had been ordered by the then Foreign Secretary, Dr David Owen.

The Rushdie fatwa was to dash many reviving hopes that accompanied the brief resumption of relations in 1989, including the optimism surrounding the release of another Briton, the businessman Roger Cooper, who had been held since 1985 in the dreadful Evin prison in the capital.

In 1989 a former colleague of Browne's reported that Cooper was "desperate" for visits from the half-dozen newly arrived British staff. One visit took place, but it appears that Cooper's particular wish to see Browne, whom he knew from Browne's first posting to Tehran from 1971 until 1974, had to go unfulfilled. Browne and three colleagues were recalled home with 24 hours' notice days after the demonstration, and Cooper was not set free until 1991.

Browne stayed in London after his unexpected return, serving from 1989 as a Foreign Office counsellor before being sent to Washington in 1990 as press and public affairs counsellor, then transferring to New York as British information head until 1994, and going home to take over as Head of the Middle East Department. It took until 1997 before the time was ripe for his return to Iran, when Mohammed Khatami – deemed a "moderate" – became President. Browne went back that year as chargé d'affaires, became Ambassador in 1999 and paved the way for the visit to Tehran by Jack Straw, the Foreign Secretary, in late September 2001, the first by so senior a British government member since the revolution.

It is Browne's posting as First Secretary and Head of Chancery in Zimbabwe, however, that his family remember with delight, an interlude when they went together on visits to the Victoria Falls and to game parks, thrilling at the sight of elephants and hippos. Browne was posted there in 1980 on the eve of independence, which had been negotiated with black majority rule, in December 1979.

With the Prince of Wales, the last Governor, Lord (Christopher) Soames, and the Foreign Secretary Lord Carrington, Browne attended the festivities that saw the end of Southern Rhodesia and the birth of Zimbabwe at midnight on 17-18 April 1980. He and his wife Diana especially enjoyed the spectacle of one of his favourite musicians, Bob Marley, singing the song "Zimbabwe" at what would be one of the last concerts of Marley's life – he died in 1981 – at the Rufaro Stadium in the capital Salisbury (now Harare). Browne, also an avid rock fan, possessed a huge collection of vinyl discs, and was enthusiastic about the music of the Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix and the Doors.

He rounded off his career as Ambassador to Denmark, retiring in 2006 after a period in London as Senior Director (Civil) of the Royal College of Defence Studies in Belgravia. He already knew, though few friends realised, that an affliction that had begun to affect his speech, and would rob him of his life at the early age of 66, was Parkinson's Disease.

Nicholas Walker Browne grew up in West Malling, Kent, the third of four sons of a Second World War army officer who later worked in intelligence. He was educated at Cheltenham College then won an open scholarship to read History at University College, Oxford, where he met his future wife Diana, a fellow Oxford student. During his first stint in Iran the couple drove from Tehran to Kabul, and it was in Iran that one of their daughters was born.

As well as his wife, children and three brothers, Browne is survived by his father, aged 97.

Nicholas Walker Browne, diplomat: born Kent 17 December 1947: CMG 1999, KBE 2002; married 1969, Diana Aldwinckle (two sons, two daughters); died Somerset 13 January 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments