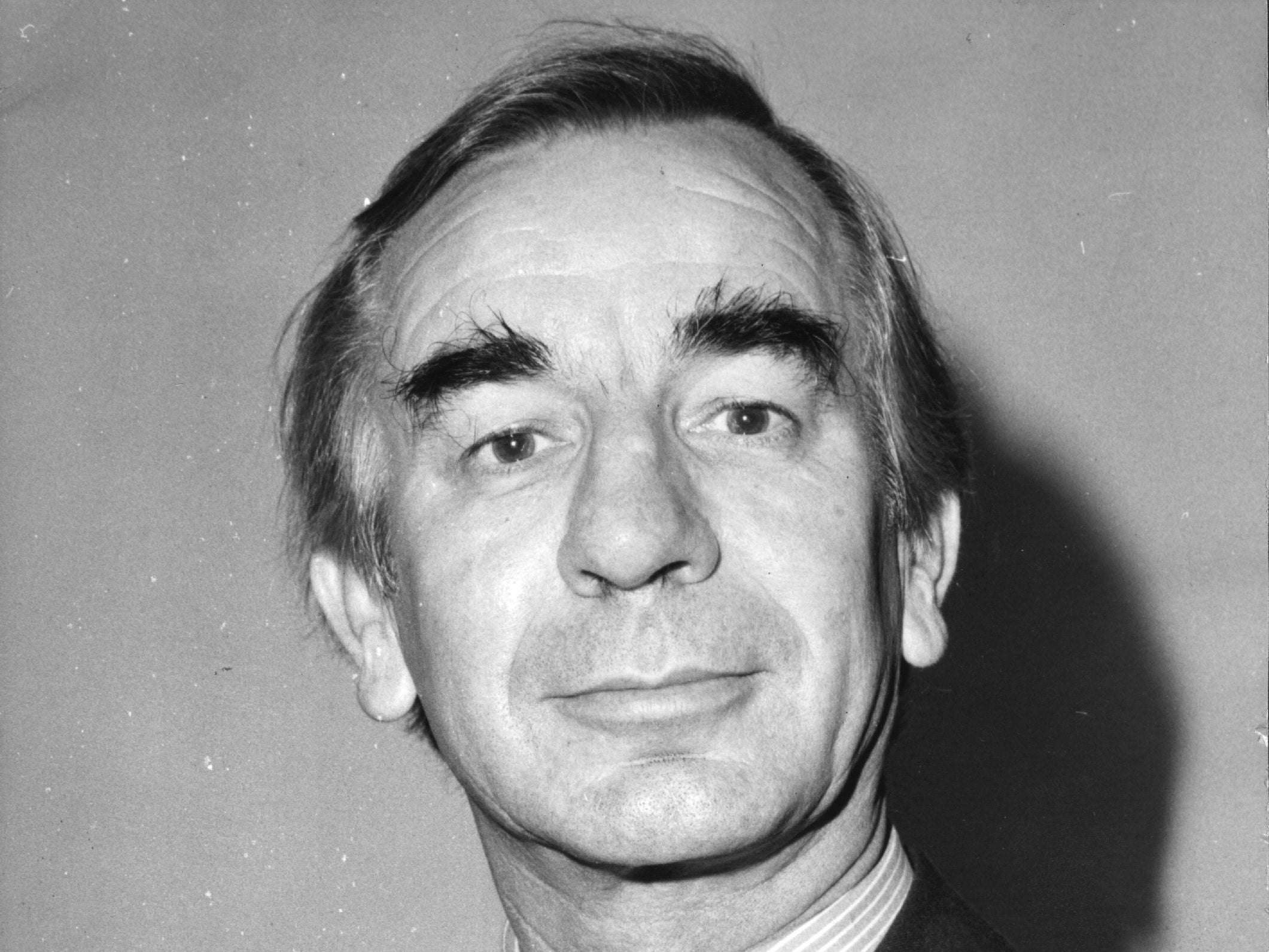

Sir James Craig: Diplomat whose grasp of Arab issues eased tensions with Saudi Arabia

He helped to heal a rift with Saudi Arabia caused by the broadcast of ITV docudrama ‘Death of a Princess’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sir James Craig was a diplomat and academic who became Britain’s top Arabist and go-to man on Anglo-Arab relations in a career that spanned four decades. Yet choosing to study Arabic was fortuitous – he told one interviewer he would “almost certainly have chosen” Celtic languages had he known the course was available at Oxford. “Then I’d have spent my life collecting folk songs in the Outer Hebrides”.

(He had wanted to study Chinese but was told the choice was Russian or Arabic. He chose the latter because it was more “exotic”.)

The son of a miner, he was not your run-of-the-mill public school British diplomat. His excellent Arabic and command of regional dialects, his understanding of the cultures and his ability to get to the heart of a problem, no matter whom he was dealing with, helped garner him much respect in the Middle East where British influence was often in flux.

Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir got to face Craig’s tough talking in a two-hour stand-up row over who started the 1967 Six Day War. And as our man in Jeddah, he was equally blunt in private with his Saudi hosts.

Despite his forthright views, expressed in his farewell ambassador’s speech, on Saudi competence, honesty and morality, he maintained good relations with the country’s royals beyond his diplomatic days.

Craig became known as an accomplished trouble-shooter following his part in ending a Palestinian aeroplane hijacking crisis in Tunis with nominal casualties; and smoothing relations with Saudi Arabia following the broadcast of the ITV drama-documentary Death of a Princess in 1980, which nearly severed diplomatic and trade relations between the two countries.

Born in a working class area of Liverpool in 1924, Albert James Macqueen Craig was the eldest of four children to James, from Scotland, and Florence. The family had Scottish roots. During the summers, he holidayed with family either in the Royal Village of Scone or in Perth.

Craig showed academic promise from an early age winning a special scholarship to the Liverpool Institute for Boys where from the age of 10 and encouraged by his Oxonian headmaster, he contemplated going to university. He won an exhibition to Queen’s College, Oxford.

Supported with a raft of such scholarships and bursaries, he secured a first in Classics Mods in 1943, and then joined the army, but returned after a year due to an illness linked back to having had tuberculosis as a child. Craig graduated with a first in Arabic and Persian in 1947.

Following a year’s postgraduate study at Magdalen College, Craig became a lecturer in Arabic at Durham University. After a year or so, in 1950, he took a sabbatical at Cairo University. In 1955 he was approached to be senior instructor at the Middle East Centre for Arabic Studies in Shemlan, then Britain’s “spy school” in the Lebanon whose history he published in 1988.

Following a suggestion to join the Foreign Office, Craig took the exam and formally joined in 1956, returning to London in 1958 to work on the Sudan Desk, without any formal training.

In 1961 he was despatched for three years to Dubai as political agent for the Trucial States, which are now the UAE. After spells in Beirut (as First Secretary) and Jeddah (Head of Chancery), Craig spent a sabbatical year at St Antony’s College, Oxford, before becoming head of the FCO’s Near East and Africa Department in 1971, which saw him travelling regularly to Europe as well as the Soviet Union.

In 1974, four Palestinians hijacked a British Airways VC-10 from Dubai to Tunis with 39 hostages. Craig was sent to negotiate; he was told by the pilot to “get things moving, otherwise there could be dire consequences”.

The hijackers demanded the release of 13 terrorists held in Egypt and two in Holland; 24 hours later, they shot dead a German bank manager and threw him to the tarmac, threatening to kill a hostage every two hours. Playing the situation “by ear”, Craig talked with the hijackers, the crew, the FCO and Downing Street, while coordinating with Arab leaders.

After 84 hours of anxious negotiations, 13 hostages were released following the arrival of the freed prisoners from Egypt. The rest were let go when those from Holland arrived. Urged by Craig, Tunisia rejected the hijackers’ asylum request and they eventually surrendered peacefully.

In 1975 Craig returned to the field as deputy commissioner in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, before moving on to become UK ambassador in Damascus, Syria, for three years until 1979. Here, he was the first British diplomat publicly to meet the PLO..

He then became ambassador in Jeddah, always a sensitive posting given Saudi Arabia’s human rights issues. In 1980 Britain and Saudi Arabia were on a collision course after the screening ITV drama-documentary Death of a Princess. Its focus was events three years earlier: 19-year-old Princess Mishaal bint Fahd al Saud had been executed by firing squad for adultery, and her lover beheaded. It also alleged that hundreds of Saudi officers were thrown out of transporter planes after a failed coup. The film particularly offended Saudi sensibilities by depicting life in an upper stratum of society where only lip-service was paid to the tenets of Islam.

Craig arrived in Jeddah with communications from London for Prince Saud Al Faisal, but on their third meeting was told to leave the country. Days later, the Saudis halted the appointment of a new London ambassador and began reviewing economic relations with Britain. The next day, a Cypriot company registered in the Channel Islands lost a £80m Saudi housing contract; overall, British firms lost £250m in orders.

After five months and numerous government apologies, Craig was able to return but Saudi hardliners blocked a visit by Foreign Secretary, Lord Carrington for talks with Saud. Craig’s rebuilding of relations was further complicated when Britain refused to accept an Arab League delegation because it included a PLO representative.

A former colleague said that Craig often found the Arabs “exasperating” but had a deep affection for the peoples and the region.

Craig married Margaret Hutchinson in 1952, and had four children; she died in 2001 and the following year he married Bernadette Hartley Lane, who survives him along with his four children.

Sir James Craig, diplomat, born 12 July 1924, died 26 September 2017

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments