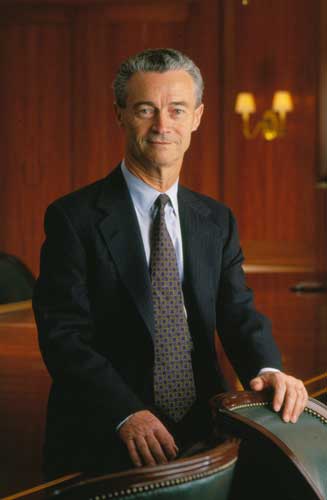

Sir Dennis Weatherstone: Son of a London Transport clerk who became one of the greatest bankers of the late 20th century

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Dennis Weatherstone was one of the greatest bankers of the last quarter of the 20th century. Little known to the public, rarely interviewed, he was very much a bankers' banker, deeply respected within the profession. Personally he was the very opposite of a major executive, described as "dapper, precise, soft-spoken. . . unfailingly polite, he moved like a cat. . . he was a man no one disliked". But, as anyone who came into contact with him knew, he "had a steely mind, especially in matters of risk".

It is safe to say that if other banks had followed the same disciplines as those he applied at Morgan Guaranty, of which he was chairman from 1990 to 1994, then the recent credit crisis would never have attained the intensity it has. Indeed, it was noticeable that JPMorgan Chase, Morgan's successor, has not suffered nearly as badly as its competitors over the past year – though Weatherstone was typical in not wanting any but the lightest regulation of banking.

He combined all the qualities required of a great banker: an instinctive grasp of market conditions, vision, calmness under pressure, and what was called "a steely insistence on evaluating the downside risk" of any given trading decision. "If you're not confused," he once said, "then you don't understand the business." One of his mottoes was "Investment has to be rational; if you can't understand it, don't do it" and he would give subordinates three chances to explain any new instruments or structures they had devised.

He required all these qualities in his career. Not only did he come from a lower middle-class background – and, as was frequently remarked, would never have reached the chairmanship of a British bank – he was English, and the first, if not the only, foreigner to chair a leading American financial institution. What made it the more amazing was that it was not any old financial institution, but "the Morgan Bank", the symbol of Wall Street over the generations for good or, mostly, bad, a symbol too of Wasp snobbery – as late as 1959, a new German recruit could be reassured that "don't worry, there are no Jews at Morgan". Effectively, Weatherstone worked for a single institution for nearly 50 years, where he served an apprenticeship in the ways of the City, especially foreign-exchange dealings, for more than two decades before any serious promotion – an inconceivable idea today.

Dennis Weatherstone was born in Islington, the son of a clerk in London Transport. But at the outbreak of the Second World War he was evacuated to Bedfordshire, where, he once said, his foster mother "instilled in me a strong sense of self-discipline". In 1946, he left school and began working, first as a bookkeeper, for the Guaranty Trust, one of the handful of American banks in a City of London that at the time was bombed out in the financial as well as the physical sense. He studied for elementary banking qualifications – his only educational qualification – through evening classes at the Northwestern Polytechnic in London, examinations which he passed when only 18, the youngest candidate ever to do so. After National Service with the RAF in Egypt, he returned to the bank as a foreign-exchange dealer, a role which instilled in him his lifelong understanding of risk.

At first, Weatherstone's career was not greatly advanced by the takeover of Guaranty Trust by Morgan in 1959. This was an admission by Morgan that it had neglected London, even selling the lease on its offices, in Lombard Street, a few years earlier. Even so, it was a pioneer; in 1960, there were only 14 American banks in the City, a number which had grown to 37 within the next decade, by which time Morgan Guaranty, as the merged bank was named, had the third-largest office of any American bank in the City.

This was the work of Lewis Preston, the key figure in Weatherstone's rise. Preston was a total contrast to Weatherstone: the archetypal "Morgan man", the grandson of a director of Rockefeller's Standard Oil, Harvard-educated, a former Marine, a hockey international, a future chairman of Morgan who became president of the World Bank. In 1966, he was appointed head of the London office and two years later was promoted to be executive vice-president of international banking. By the end of the 1960s, Morgan was at the heart of the new, totally international, completely unregulated market in "Eurobonds" and other securities. Morgan even set up Euroclear, responsible for the clearing and settlement of deals in these securities.

Although Weatherstone was still, after 20 years, a relatively junior clerk, Preston had quickly appreciated qualities of someone "who seemed to know everything that was going on in the branch" and when he moved to New York in 1971 Weatherstone moved with him, following him up the career ladder for the next two decades.

From 1980 to 1986 Weatherstone was chairman of the executive committee, where he had to help the bank recover from severe losses in loans to Latin-American countries. As president until 1990, he and Preston ensured that Morgan was virtually the only major financial institution to stay aloof from the madcap and costly purchase of British stockbrokers and merchant banks, which cost its rivals uncounted billions after the freeing of London's financial structure, known as the "Big Bang", in 1986. In 1990, Weatherstone succeeded Preston as chairman and chief executive officer, and was promptly knighted for his services to banking.

Weatherstone also followed Preston in believing that, in the age of Gordon Gekko, the Morgan tradition of "doing first-class business in a first-class way" through continuing relationships with "first-class" companies was no longer viable. Moreover, major companies were no longer dependent on their banks for capital, relying rather on issues of bonds and shares. Instead, Morgan had to become a firm relying on the issue and trading in financial securities. The move, said Weatherstone, allowed the bank "to provide any financial service, whether it be a loan, advice or a securities offering. . . I think we realised that we had to change or perish." But whereas "Preston was a traditional commercial banker trying to push the bank into the markets," in the words of the financial journalist Robert Teitelman, "Weatherstone was a true man of the markets. . . Preston now seems like a great figure, but one from an impossibly remote age."

This type of activity had been forbidden by the Glass-Steagall Act, passed in the early 1930s to divide commercial banks such as Morgan from "investment banks" such as its former subsidiary Morgan Stanley. But shortly after his arrival in the chair at Morgan, he got permission to act as underwriter and trader in securities, the first, and crucial, breach in the wall set up by Glass-Steagall, nine years before the act itself was repealed. Before Weatherstone retired four years later, three-quarters of Morgan's revenues were coming from investment-banking activities – such as trading profits and fees from issuing securities – and it was recognised as one of the leading securities firms in the United States. The repeal itself led to a series of mergers in Wall Street, notably that of Morgan with Chase Manhattan in 2000.

Under Weatherstone, Morgan instituted a system to ensure the bank knew exactly how much risk every department was running in the form of a one-page daily report from every department head showing potential losses, a system widely, though regrettably not universally, followed by competing banks. Unfortunately, one of his major innovations, the use of derivatives, a system of spreading risk – albeit in his case to reduce risk rather than increase exposure to risk – turned out to be a Frankenstein's monster in the hands of less professional bankers and contributed greatly to the present crisis.

In 1994, Morgan was named by Forbes magazine as one of America's Top 10 Most Admired Companies. That year, Weatherstone retired – he stuck rigidly to Morgan's rules that all executives should retire on or before their 65th birthday. His retirement enabled him to devote more time to his passion for tennis but he was naturally in great demand as a non-executive director of such major groups as the New York Stock Exchange, General Motors and Air Liquide. He was also an outside candidate as successor to Robin Leigh-Pemberton as Governor of the Bank of England, though he proved a friend of and powerful adviser to Leigh-Pemberton's successor, Eddie George. For five years he served on the Board of Banking Supervision, until this extremely effective body was abolished on the introduction of Gordon Brown's "tripartite" system.

Weatherstone's lifestyle was the precise opposite of that of the majority of his colleagues. He remained with Marion, whom he had married in 1959, and lived modestly, in Darien, Connecticut.

Nicholas Faith

Dennis Weatherstone, banker: born London 29 November 1930; senior vice-president, Morgan Guaranty Trust Co (later JP Morgan & Co) 1972-77, executive vice-president 1977-79, treasurer 1977-79, vice-chairman 1979-80, chairman, executive committee 1980-86, president 1987-89, chairman and chief executive officer 1990-94; KBE 1990; married 1959 Marion Blunsum (one son, three daughters); died Stamford, Connecticut 13 June 2008.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments