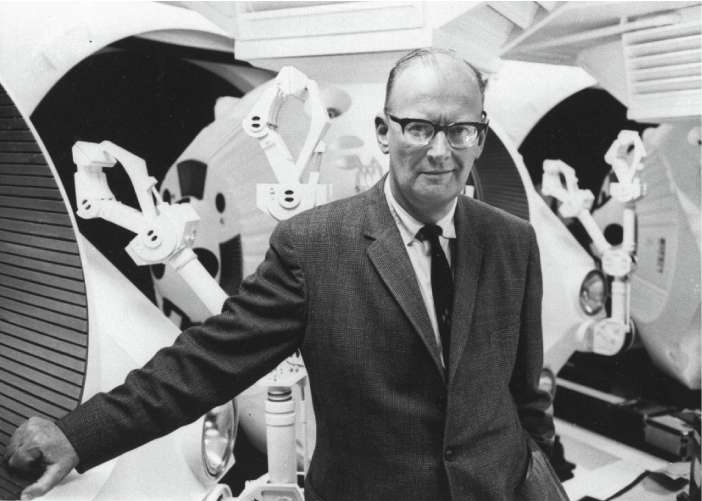

Sir Arthur C. Clarke: Science-fiction writer best known for '2001: A Space Odyssey'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Next to H.G. Wells, Arthur C. Clarke was the widest-known English writer of science fiction of the 20th century. Like Wells, he was also a voluminous author of non-fiction; both men were great popularisers of science, with styles of such pellucidity that the great issues of the century – if only for a moment or two of relief – seemed solvable.

It is, however, almost certainly for their science fiction that these two great and prominent Englishmen of the world will be remembered. Both were honoured in the United States – for the past century the main home of the SF genre – which understandably tended to advocate American dreams of the future. In their different ways, however, both men escaped that hegemony. Wells escaped the dominance of the American form by precursing it, Clarke by surviving it.

Although both men were English, they aimed their work – fiction, film scripts, non-fiction – at the whole human family, many of whose members are conspicuously less evangelical about the future than Americans have been. In their later years both were treated, and thought of themselves, as spokesmen for humanity at large. A sometimes touching vanity about the prominence they had earned marked each man, though Wells laced his amour propre with ire. Clarke's, at least until the terrible year of 1998, seemed unassailably serene. He spoke for the highest hopes of the 20th century.

Arthur Charles Clarke was born in Minehead, Somerset, before the end of the First World War, and remained loyal to his roots for the rest of his life, though his last half-century was spent mostly abroad. He described his early years in Astounding Days: a science fictional autobiography (1989), acknowledging the liberating power of the American pulp science-fiction magazines of the early 1930s.

But the book that transformed his imaginative life was Olaf Stapledon's Last and First Men, which he read soon after its first publication in 1930. The metaphysical scope of Stapledon's aeon-spanning vistas, and his stately pessimism about the ultimate fate of Homo sapiens, clearly affected Clarke at a profound level; at the heart of his finest novels, like Childhood's End (1953) and Rendezvous at Rama (1973), a serene and lyrical impassivity about the fate of individual humans transforms plots that might otherwise seem routine.

By 1937, the two-fold nature of Clarke's eventual career began to take shape. He had joined the British Interplanetary Society, for which he twice served as Chairman, in 1946-47 and 1950-53, and he had begun to publish fiction in an amateur magazine. During these years he worked as an Assistant Auditor in a British government department. When the Second World War came he joined the Royal Air Force, serving 1941-46, eventually becoming a radar instructor and technical officer on the first Ground Controlled Approach radar.

In 1945, before leaving the service with the rank of Flight Lieutenant, he published a technical paper, "Extraterrestrial Relays", in Wireless World; it may not be his most widely read non-fiction piece, but it has been by far the most influential, for in it he was the first to propose (and to describe) a geosynchronous communications satellite. It was an idea that continues to transform our world.

Not until 1946 did "Rescue Party", the first story he wrote for professional publication, appear in Astounding Science Fiction. Against the Fall of Night (1953), a novel combining Stapledonian perspectives with a fey juvenile protagonist, was published in magazine form two years later, but Clarke's first published volume, the first of several he wrote on the subject, was Interplanetary Flight (1950). Beneath the technical literacy and lucid, popularising smoothness of this book and its successors, there lies a powerful sense of urgency and longing. Humanity (Clarke suggests, carrying on from Wells) must transcend the physical trap of this single planet, which we are in any case destroying, or humanity will not survive.

Several of the novels of the early 1950s, like Prelude to Space and The Sands of Mars (both 1951), read almost like technical manuals for the first steps into space; although they suffer as fiction, they manage to convey impressively a sense of the possibility of escape, and they helped shape the minds of the aspiring young rocket scientists who would grow up to create Nasa. But the mild triumphalism of tales like these was undercut by Clarke's best work – novels like Childhood's End, which was also written in the early 1950s – tales whose perspectives are vast, and which surefootedly convey a sense that the technologies and aspirations of humanity are evanescent.

Even the short fiction, much of it datedly jocular, reflects this sharp dichotomy between the advocacy of technological expedients and the ironies that undercut the mayfly aspirations of the human species. Clarke's most famous short story, "The Nine Billion Names of God" (1953), rewards a triumph of science with the calm extinction of the universe. An Asian sect hires a computer expert to tabulate all the possible names of God, in the belief that the universe will end when that essential task has been accomplished. The computer makes short shrift of the task. And the stars begin to go out . . .

Clarke's own life clearly shared something of the transcendental longings of his fiction. In the early 1950s he discovered, through skin-diving, the southern oceans, and in 1954 he moved to Sri Lanka, where he remained until his death. Here, in some isolation, but close to his beloved ocean, he turned more and more to works of celebratory non-fiction about the sea, several of them, like Indian Ocean Adventure (1961), written with his diving partner Mike Wilson. The fiction of this period either reflected his new interests, like The Deep Range (1957), or was relatively inconsequential.

The extraordinary fame of his later years began, of course, with Stanley Kubrick, who asked him to expand an early short story, "The Sentinel" (1951), into the script that led to the enormous success of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). The application of new cinematic technologies to a script of literacy and scope made this the first science-fiction film to express the imaginative and speculative reach of the genre at its best. For many viewers whose knowledge of science fiction may not have been extensive, Clarke became an almost ubiquitous guru of future-studies, performing his public roles with a dignity not unmixed with complacence (even before the war he had been nicknamed "Ego" by his friends, ostensibly after the initials of a pseudonym he then used).

In later years he became a household word after the release of his two main television series, Arthur C. Clarke's Mysterious World (1980) and Arthur C. Clarke's World of Strange Powers (1985), and his work as commentator for the American CBS television network on the lunar flights of Apollos 11, 12 and 15.

With the success of 2001 and its sequels, Clarke returned more actively to the writing of fiction, and Rendezvous with Rama (1973), which won all four major awards for science fiction in 1973, was soon followed by Imperial Earth (1975) and The Fountains of Paradise (1979), his last novel to make a genuinely innovatory suggestion about future technologies. The physical link by elevator he here suggests between Earth and a geosynchronous space station may seem merely fantastical, but is closely argued. In future years, it may well seem an inspired prediction.

Illness now began to dog Clarke's steps. In 1985 he was diagnosed as suffering from motor neurone disease and given two years to live; only in 1988 was this discovered to be a misdiagnosis, though he continued to suffer from the effects of the polio he had contracted as a young man.

Honours and awards were numerous. He won the Unesco Kalinga Prize in 1961, the American Association for the Advancement of Science Westinghouse Award in 1969, and from 1979 was Chancellor of the University of Moratuwa in Sri Lanka, only one of the influential roles he played in his adopted country; in 1986 he was made a Nebula Awards Grand Master by the Science Fiction Writers of America. In turn, he established foundations and grants; such as the annual Arthur C. Clarke Award (at first for £1,000, increased in 2001 to £2,001) for the best British science-fiction novel of the year, given annually in London since 1986.

Clarke's last years should have been serenely plenipotential. He had been appointed CBE in 1989, and a knighthood was announced in the New Year's Honours of 1998; he had planned to be formally invested when the Prince of Wales visited Sri Lanka that February, but as it turned out, the ceremony had to be called off. On 1 February, the Sunday Mirror published allegations that Clarke had paid for sex with under-age boys. Clarke – by then 80, and in a wheelchair for 15 years – categorically denied the allegations. The Sri Lankan authorities, after an extensive investigation of the story, found no evidence to sustain them and cleared the author – who remained deeply respected in Sri Lanka.

Lingering questions about the nature of Clarke's sexuality seemed merely intrusive. Despite his position as a world-famous popular guru of the future, and as the 20th-century's most eminent science-fiction writer still alive and active, he had managed to live his life in private for more than half a century, with no breath of controversy or tabloid prurience until the abortive "exposure" of 1998. He was married, briefly, in the 1950s, to Marilyn Mayfield. The rest of his life, it seems, was devoted mainly to work. Until the beginning of this year he maintained a vast correspondence, mostly by e-mail. Leslie Ekanayake, who shared his passion for skin-diving, was his companion for many years until his death in 1977 in a motorcycle accident. Leslie's brother, with his wife and children, then shared Clarke's home. But he maintained his privacy until the end.

In any case, well before the celebrations marking 2001 – a year he had, in a sense, made his own – Clarke had fully regained his old serenity, and his last years were soothed by continuing acclaim. He had described near-space so vividly that aspiring astronauts dreamed his visions, and made them come true. He had written dozens of books which are a central record of what the 20th century hoped to accomplish. He had briefed the world about what to do next. It was not his fault that the journey has just begun.

John Clute

A glance round his study, or "Ego Chamber" as he liked to call it, gave visitors to Arthur C. Clarke's home in Colombo the bare bones of his story, writes Simon Welfare. The walls were covered with the memorabilia of a long, successful and influential life: framed citations, an Oscar nomination, photographs taken with the world's movers and shakers, tributes from astronauts, cosmonauts and scientists, and a faded, but prized, copy of his famous Wireless World satellite paper. His shelves were crammed with awards and countless editions of his best-selling books. And the daily ritual of opening the morning post, and more recently the countless emails that somehow reached him at his secret inbox, were other reminders that Clarke was one of the few authors who could claim, with justification, that his words had changed the world.

Yet the Arthur Clarke whom those same visitors invariably found lounging, wrapped in a colourful sarong, on the study sofa, was far keener to share his enthusiasm for the present and future than to talk about the past. A hand outstretched in greeting was usually filled with a press cutting that had caught his eye a few minutes earlier; books on obscure subjects were dusted down to help in the discussion; and video evidence produced at the click of the remote control that sometimes seemed to be an extension of his hand.

It was during one of these unpredictable mornings, which we spent away from his study on his favourite beach at Unawatuna, that the seeds of his famous television series took root. He began by telling me how his love of diving had taken him to Sri Lanka, and how, within hours of stopping off in Colombo en route to Australia's Great Barrier Reef, he had fallen in love with the island. Typically, this was the prelude to the far more exotic tale of a schooner, The Pearl, which, somewhere off that very shore, had been enveloped in the tentacles of a giant squid and dragged beneath the waves. A few years later, this was one of many tales that Clarke shared with television viewers in Arthur C. Clarke's Mysterious World.

Probably the first factual entertainment series shown on British television, Mysterious World was an instant hit, particularly with young viewers, who voted it their favourite new programme of 1980. The crystal skull in its titles became an icon of the age and Alan Hawkshaw's spooky theme music held millions in its thrall. Although, at first sight, many of the stories appeared preposterous – they included UFOs, Ape Men, and weird objects that had fallen from the sky – Clarke felt they merited serious, if sceptical, consideration.

"The universe is such a strange and wonderful place that reality will always outrun the wildest imagination," he said. "There will always be things unknown, and perhaps unknowable." He could be uncompromising in his scepticism and mischievously witty in his put-downs of outlandish claims, yet he happily acknowledged that there were many mysteries that he could not explain.

In the midday break, he would often travel home, eat lunch, deal with his correspondence, have a nap and rewrite the afternoon's scripts: all within the allotted hour. Mysterious World was a notable start to a new career that made him a household name far beyond the world of sci-fi. Three more series followed, and the 52 programmes, now something of a cult, have been shown around the planet. The accompanying books were all best-sellers: Arthur particularly enjoyed the publishers' claim that the first had outsold all their other offerings, bar Life on Earth and the Bible.

Between takes on location, Arthur often amused himself, and us, by concocting new, and often outrageous, epitaphs. We gave a prize for the best. For once, I think, it was written by someone else, but it was fitting for a man whose vision had ranged so inspiringly across the seas of space. It read: "I have loved the stars too fondly to be fearful of the night."

Arthur Charles Clarke, writer and broadcaster: born Minehead, Somerset 16 December 1917; Chairman, British Interplanetary Society 1946-47, 1950-53; Fellow, King's College London 1977-2008; Chancellor, Moratuwa University, Sri Lanka 1979-2002; CBE 1989; Kt 1998; married 1953 Marilyn Mayfield (marriage dissolved 1964); died Colombo, Sri Lanka 19 March 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments