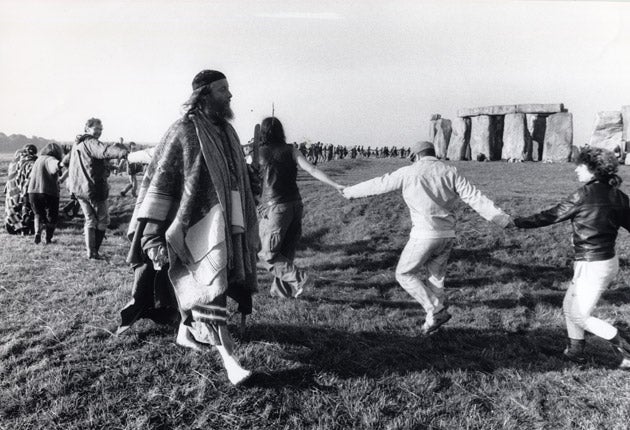

Sid Rawle: Social activist known as King of the Hippies

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sid Rawle was known as King of the Hippies, a title bestowed on him decades ago by a tabloid newspaper, probably with heavy irony.

Yet the designation turned out to be entirely appropriate, for he adhered to the hippie approach for all of his 64 years.

It was appropriate that the heart attack which killed him should have struck as he sat around a campfire following a summer camp. He spent his life in squats, in battered vans, caravans and teepees, at love-ins and happenings. Many others were hippies for a time but then moved on to other lifestyles, raising families, seeking jobs and paying off mortgages. Not Sid Rawle. In normal society's terms he grew old disgracefully, maintaining the habits of the 1967 Summer of Love and steadfastly ignoring standard sexual and social taboos. As the jargon of the '60s would have it, he simply kept on trucking.

Two decades ago, Rawle's way of life was captured by the writer Jeremy Sandford. "When I knocked on the door of his van it was opened by his three-year-old daughter, wearing the fashionable bottomless look," Sandford wrote. "Sid introduced me to a rather posh young female doctor who, he explained, had been sharing his bed for the night. 'Well, as for Sid,' said the doctor, 'the point is that he is, well, always one hundred per cent Sid.'

"Sid also introduced me to the superbly beautiful mother of his children, who was happily camped with a swarthy lover nearby. 'She's my lady,' Sid explained, 'but we neither of us believe in sexual exclusivity. I could never accept a life in which, when I meet a lovely lady, one thing doesn't sometimes lead to another.'"

Rawle's sartorial style was, according to Sandford, as free and easyas his sexual habits: "He was wearing a bulky sweater and blue underpants with holes in interesting places.Sometimes as we spoke he ruminatively stroked himself. The ensemble was topped with a striking, biblical-style cloak."

There was, however, more to Sid Rawle than self-indulgence in decades of free love. He had charisma and leadership qualities and a certain talent for negotiating with authority. This last was a useful quality in that he was forever coming up against police and locals who wanted only to see him and his friends – who sometimes travelled with him in convoy – move on to someone else's backyard.

He was prepared to indulge in a little give and take, so that police often came to knock on the door of his van to seek a diplomatically negotiated settlement. One who observed him said, "He was a master at peace-makingand bridge-building. In a dispute, he could talk to anybody – police chiefs, biker-gang leaders, junkies and councillors, and convince them to come to a compromise."

After his death, a perhaps unexpected tribute came from CouncillorNorman Stephens, who representsthe Forest of Dean, where Rawleorganised camps and festivals."Although Sid chose an alternative lifestyle he was also a gentlemanand a man of peace," Stephens said. "He had run camps for a number of years and the locals had taken the festivals to their heart. There were never any problems."

There were, however, sizeable problems elsewhere, especially in 1974, when the Duke of Edinburgh was not amused by an annual festival which Rawle helped to stage in Windsor Great Park. Police moved in, making 200 arrests. A year later, Rawle was jailed forseveral months for planning a similar event. Then in 1985, new age travellers and police clashed in Cambridgeshire, with 500 arrests in what was knownas the Battle of the Beanfield.

In another episode John Lennon offered Rawle the use of Dorinish, an island he owned off the west coast of Ireland. Rawle persuaded 25 people to follow him there to establish a settlement. But it lasted only two years, the fierce Atlantic gales proving too powerful for the commune's tents.

In an odd episode in the late 1990s, Rawle took exception when the Halifax building society featured him, without his permission, in a major advertising campaign when it wasseeking to convert itself into a bank. A photograph showed him holdinga baby, with a speech bubble coming out of his mouth saying, "Be a part of something big, man". It had been taken years earlier as Rawle presided at a baby-naming ceremony at a Stonehenge festival.

"These are words put into my mouth that I disagree with and that make me look stupid," Rawle complained. "I knew nothing about this until numerous people called me from all over the country saying they'd seen me on hoardings. They either think I've sold out on my principles or that I must have done rather well out of it financially. I feel used and abused."

He was a member of both the Green Party and the Ecology Party which preceded it, feeling strongly about land issues. Born in Somerset, he loved Exmoor and its hills as a boy.

During his life he stuck to a straightforward philosophy, strongly reminiscent of the old hippie attitudes. "Shared out equally," he maintained, "there would be a couple of acres for every adult living in Britain. That would mean each family or group could have a reasonably sized smallholding of 10 or 20 acres and learn once again to become self-sufficient. That's all we want, myself and the squatters and travellers and other people in the many projects I've been involved with.

"Just a few square yards of this land that we can, in wartime, be asked to go out and die for. In peace time is it too much to ask for just a few square yards of our green and pleasant land to rear our children on?"

This was not a particularly original or advanced idea for Rawle to leave behind: his main legacy was more in the physical line. This took the form of at least seven children, and probably more. Some women, however, found his 1960s brand of sexual licence unpalatable, seeing it as basically a recasting of old-fashioned sexism. Such criticism did not greatly trouble him. A contemporary recalled: "He had flaming red hair and around the free festivals the big joke about him was that any red-haired child around was probably one of his.

"I was with him once when a woman carrying a red-haired baby walked by. She held up the baby and called out to him, 'This is another one of yours, Sid!' and he just chuckled."

Sidney William Rawle, hippie and social activist: born Bridgwater, Somerset 1 October 1945; several children; died Westbury-on-Severn, Gloucestershire 31 August 2010.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments