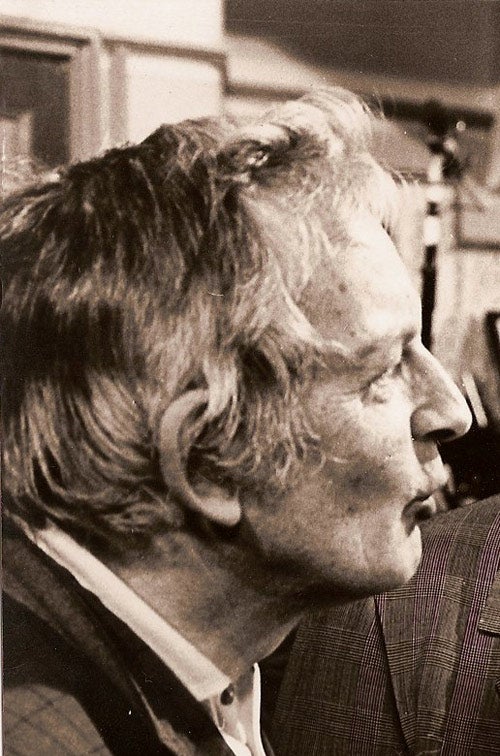

Russell Lloyd: John Huston's film editor, who began his career with Korda

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Hugh Russell Lloyd, film editor: born Swansea, Glamorgan 16 January 1916; married 1943 Rosamund John (one son; marriage dissolved 1949), 1950 Valerie Cox (three sons, one daughter); died Cranleigh, Surrey 21 January 2008.

Russell Lloyd would always say that he was practically born into the film industry: "My mother's labour pains started on a Saturday night while at the local cinema near Swansea in Wales. I was born Sunday morning." One of Britain's most respected film editors, Lloyd amassed nearly 50 feature editing credits, including 11 for the director John Huston. Lloyd's Academy Award nomination for Huston's The Man Who Would Be King (1975) crowned a career which had begun in the great days of Alexander Korda.

Obsessed with the cinema from an early age, Lloyd ended his schooling at Bradfield College in Berkshire and then worked for almost a year as a projectionist in Swansea. He bombarded British film studios with letters applying for any position in the camera department and eventually received a telegram from Korda's production executive at London Films, David Cunynghame, inviting him to report to Elstree and offering him work as a "numbering boy" synchronising film rushes under the cutting-room head Harold Young. As Lloyd later reported: "You could imagine my dismay – my chance of being that great cameraman destroyed! However, I've never since regretted that twist of fate."

In those days each film was handled by one editor and one assistant, but so active was Korda's production programme that Young was promoted swiftly to direct The Scarlet Pimpernel (1934) and William Hornbeck, an American, was brought over to replace him, with Francis D. "Pete" Lyon also recruited from Hollywood. Lloyd was promoted to assist them on Moscow Nights (1935).

He followed this by assisting on a series of Korda classics, amongst them Sanders of the River (1935), Rembrandt (1936) and Things to Come (also 1936), invaluable experience. In fact, he only ever assisted three editors, all Americans: Hornbeck, Lyon and the Texan Jack Dennis, whose hard-drinking habits and regular leaves of absence led to Lloyd having to edit sequences in his stead.

On The Squeaker (1937), the director William K. Howard had to view a cut sequence prior to striking the set. In Dennis's absence, Lloyd edited the sequence himself. Dennis was grateful, and not only suggested Lloyd should continue to edit sequences on The Squeaker but also that he should receive the editing credit. This led to other jobs with Howard and another visiting US director, Thornton Freeland, but at the outbreak of the Second World War Lloyd volunteered for the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR).

He was brought back from active duty at sea and commissioned by the Crown Film Unit to edit a documentary on submarines called Close Quarters (1943) which led to his producing, directing and also writing A Harbour Goes to France (1944) for the Army Film Unit.

The war over, Lloyd edited School for Secrets (1946) for Peter Ustinov, a propagandist piece about the use of radar during the war, and, again for Ustinov, a popular comedy, Vice-Versa (1948). His directorial ambitions were partly fulfilled when Korda invited him to film second unit for Julien Duvivier's Anna Karenina (1948, starring Vivien Leigh), but the film was not a success. Nevertheless, Lloyd secured a co-directing assignment with Emlyn Williams on The Last Days of Dolwyn (1949), necessitated because Williams was also starring, and needed another eye behind the camera. "Emlyn used to talk to the people who were going to be in the scene," recalled Lloyd, "and then I would decide where the camera went and what they did."

But the British film industry was going through what could be seen with hindsight to be one of its regular periodic depressions, and it was not a good time for a newcomer to direction. After trying to set up a solo project, Lloyd "thought I'd better go back to cutting where I was more or less of sure of getting a job". Korda had bought up Lloyd's contract and used him in an advisory capacity but Korda's glory days were, alas, nearing an end.

In 1950 Lloyd was hired to direct second unit and location sequences for Walt Disney's first British action feature, the glorious Treasure Island, and shot exquisite Technicolor material, but, as so often happened in an almost unbearably fickle industry, there was no follow-up.

Returning to the cutting room, Lloyd was fortunate to edit a series of American-financed features with US stars and directors, including I'll Get You For This (1951), Saturday Island (1952) and Rough Shoot (1953). More prestigious in terms of UK cinema, he edited The Sea Shall Not Have Them (1954), a wartime naval saga directed by Lewis Gilbert starring Dirk Bogarde and Michael Redgrave (of the title and stars Noël Coward famously quipped: "I don't see why not. Everybody else has.")

In 1956 John Huston was preparing Moby Dick for Warner Bros to star Gregory Peck as Ahab, but his regular editor was contracted to another film company. Lloyd, an admirer of Huston's work, found out that the director was shooting whale tests prior to principle photography, and quite simply arranged to visit Huston in Milford Haven in order to apply for the editing job. They met, clicked, entered into long, ecstatic discussions, and then Huston said simply, "Let's get started."

Lloyd was involved for well over a year, beginning a relationship that would continue through 11 features, of which Moby Dick (1956) afforded Lloyd a rare directorial moment. A Warner Bros executive noted the absence of a character assumed to have perished when the ship went down – Lloyd found some frames, ran them backwards, had the art department construct the matching miniature, and built up a shot wherein the character is dispatched by the collapsing ship's rigging. Huston was delighted with the result and ever afterwards exited his films when shooting was over, and entrusted post-production totally to Lloyd.

Lloyd followed up Moby Dick with Huston's Heaven Knows, Mr Allison (1957), a Robert Mitchum-Deborah Kerr two-hander for Fox, who were so delighted that Lloyd was then hired to edit a series of CinemaScope features for the Fox chief Darryl F. Zanuck, including two featuring Zanuck's lady of the moment Juliette Greco, who personally thanked Lloyd for arguing with Zanuck over choice of takes. "I don't know what you do with Darryl in the dark, but he loves you!" she said.

After The Roots of Heaven (1958) with both Huston and Greco, Lloyd's next Huston assignment was the western The Unforgiven (1960) with Burt Lancaster and Audrey Hepburn, on which shooting was delayed when Hepburn took a bad fall from a horse. Lloyd used the hiatus to learn how to fly, a new passion which almost equalled the pleasure of playing endless rounds of golf with Lancaster before shooting resumed.

Lloyd was particularly respected within the industry for his work, in between assignments for Huston, on Of Human Bondage (1964), a film which had gone through the hands of three directors, and on which Lloyd created a whole new sequence out of trims and rushes, and also for editing Fox's mammoth title Cleopatra (1963) for the director Rouben Mamoulian at Pinewood.

Lloyd's remarkable relationship with Huston reached its apogee with The Man Who Would Be King (1975) in which the editor's and director's styles meshed seamlessly, for both were opposed to the then (and still) current trend for overcutting action sequences, and there is a tremendous moment of pure cinema when Sean Connery falls to his doom from a collapsing rope bridge in a single shot. Lloyd received an Academy Award nomination for his editing.

But such a style of classical editing began to be deemed "old-fashioned" by young Turks from television and like many film technicians of Lloyd's generation, his work veered between sex films such as Swedish Fly Girls (1971) and The Amorous Milkman (1975) and foreign features such as Turnaround (1986) and Foxtrot (1988). Despite his being enlisted to salvage such movies as Caligula (1979) and Absolute Beginners (1986), after The Dive in 1989, there were no more offers.

Tony Sloman

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments