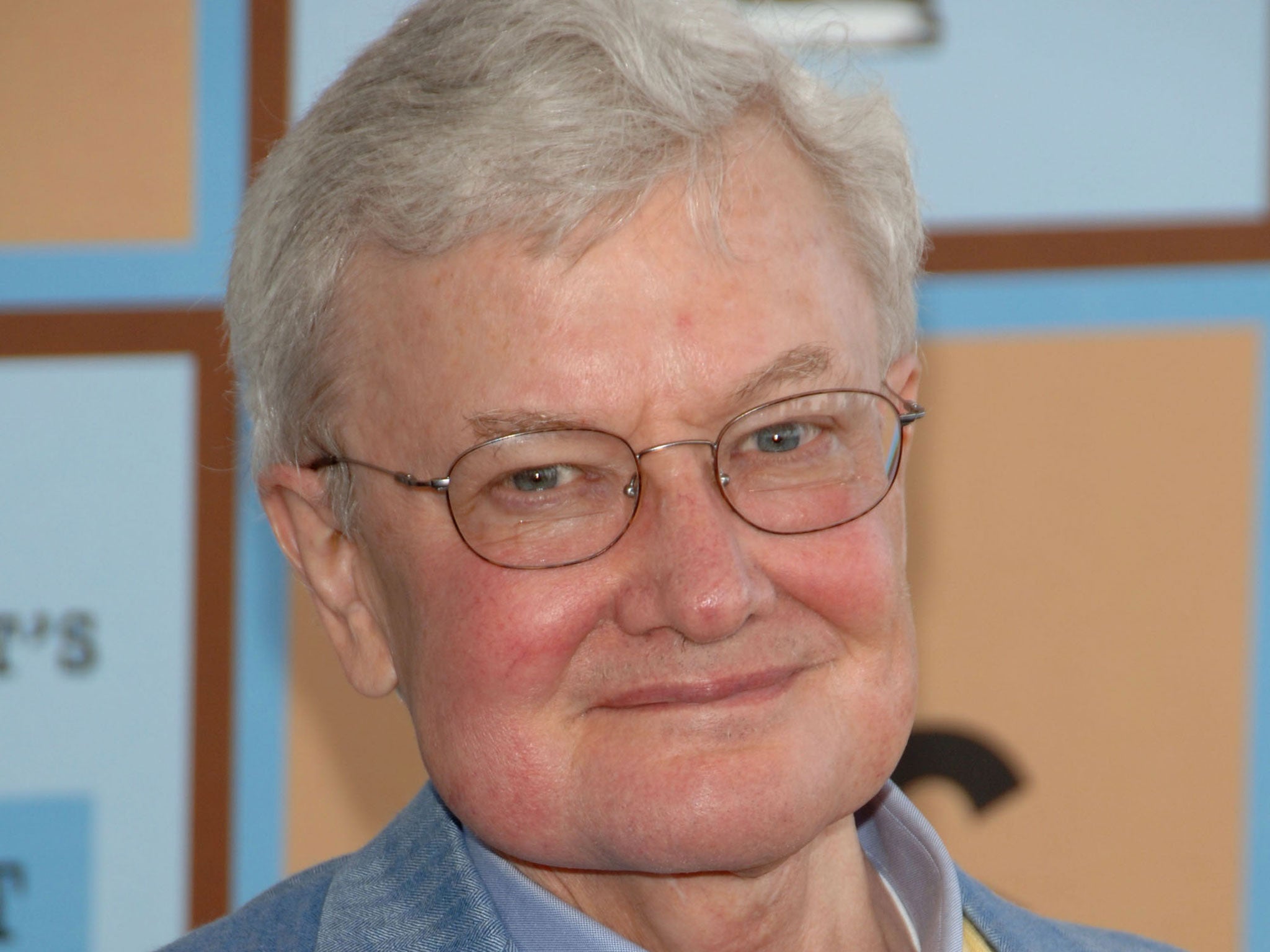

Roger Ebert: Film critic whose work crackled with his wit, acumen and occasional sarcasm

He recalled the days when the stars would say anything, ‘and not care if you quoted them’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Roger Ebert was the first writer to win a Pulitzer Prize for film criticism, and was one of the world’s best known film critics, regarded as the most influential in the US. His reviews for the Chicago Sun-Times were syndicated to over 200 newspapers, and the television show he hosted with Gene Siskel for over 20 years made the pair, and their trademark thumbs up or down verdicts, nationwide favourites. Ebert was revered for his passionate love of movies, his acumen in celebrating the first-rate, and his witty demolition of the mediocre or worse. “No good film is too long,” he wrote. “No bad movie is short enough.”

His writing was noted, too, for the occasionally mocking sarcasm he would bring to an unfavourable review – of M Night Shyamalan’s The Village, he wrote of the final revelation of the secret “twist”: “it’s so witless, in fact, that when we do discover the secret, we want to rewind the film so we don’t know the secret anymore.” Occasionally his reviews took the form of mock interviews or conversations, stories, poems or songs. Of the contentious system of star ratings, he said, “The star rating system is relative, not absolute. When you ask a friend if Hellboy is any good, you’re not asking if it’s any good compared to Mystic River, you’re asking if it’s any good compared to The Punisher. And my answer would be, on a scale of one to four, if Superman is four, then Hellboy is three and The Punisher is two.”

Fearless in his criticism of the US ratings board, the Motion Picture Association of America, he accused them of frequently misjudging their guidelines on suitability for children – he found it “stupefying” that The Exorcist was awarded an “R” rating, which meant that children could see the film accompanied by an adult, instead of the stricter “X”. When his unfavourable review of Vincent Gallo’s The Brown Bunny prompted Gallo to call him a “fat pig”, Ebert adapted a famous Winston Churchill riposte, stating, “I will one day be thin but Vincent Gallo will always be the director of The Brown Bunny.”

Ebert was also a prolific lecturer and he wrote numerous books, essays and articles. Since 2002 he had been battling thyroid cancer, learning to speak with a voice machine and appearing on television with a prosthetic jaw.

Born Roger Joseph Ebert in Urbana, Illinois, in 1942, he remembered his electrician father and bookkeeper mother as staunch liberals who prayed for Harry S Truman’s victory in the 1948 elections. He became interested in journalism while attending Urbana High School. He was only 15 when he began writing on sports for the News-Gazette in Champaign, Illinois, and the following summer he was moved to the city desk where, he recalled, “under the instruction of patient veterans, I learned the newspaper business as an apprentice.” He was also a regular contributor to science-fiction magazines, and in his senior year at high school he was co-editor of the college newspaper, The Echo.

After receiving a degree from the University of Illinois, where he edited The Daily Illini, he studied English under a scholarship at the University of Cape Town. He was a doctoral candidate in English at the University of Chicago when, in 1967, he was offered the post of film critic at the Chicago Sun-Times. He later described it as a period when “protective publicists were not so universal, and I was able to spend a lot of time with interview subjects who would, in such cases as Lee Marvin, John Wayne, Groucho Marx and Robert Altman, say anything, literally anything, and not care if you quoted them.”

Ebert lobbied for the elimination of the Chicago censorship board, and he became actively involved in film-making when, in 1970, he wrote the screenplay for Russ Meyer’s Beyond the Valley of the Dolls. Though critically panned, it has, like most of Meyer’s work, found a cult following. He also teamed with Meyer on Beyond the Valley of the Ultra-Vixens and the Sex Pistols film Who Killed Bambi? Though it was never completed, scenes from it were used in Julien Temple’s Pistols film The Great Rock’n’Roll Swindle. The DVD of Beyond the Valley of the Dolls has a commentary by Ebert, who also provided audio commentaries for DVDs of such films as Citizen Kane, Casablanca and Floating Weeds.

Ebert won the Pulitzer Prize in 1975 for his Sun-Times reviews. In 1976 he teamed with Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune to host Coming Soon To A Theater Near You, a weekly television show of film criticism for a public broadcasting station in Chicago. The following year, retitled Sneak Previews, the show was broadcasting nationally, and it went on to receive seven Emmy nominations. In 1982, the pair started a syndicated show called At the Movies, later retitled Siskel and Ebert.

They were by then a famous team, noted particularly for the lively discussions that ensued when they disagreed on a film’s quality, their thumbs-up or thumbs-down verdicts becoming so identifiable that the system became a registered trademark, owned by the estates of Siskel and Ebert. “I came up with the idea and the reason that Siskel and I were able to trademark it is that the phrase ‘two thumbs up’ in connection with movies had never been used,” he said. Their fame was such that they were frequently parodied, with Ebert’s short, heavy-set and bespectacled frame complemented by Siskel’s tall, lean and balding figure. Ebert wrote, “Tall and thin, short and fat, Laurel and Hardy. We were parodied by Saturday Night Live, by Bob Hope and Danny Thomas and, the ultimate horror, in the pages of Mad magazine.”

Though at first their relationship on screen was edgy, Ebert wrote that Siskel “became less like a friend than a brother.” Despite their mainstream audience they were staunch champions of the small-scale and offbeat movie, and Ebert once lamented that cinemas outside the major cities were “booked by computer from Hollywood with no regard to local tastes, making high-quality independent and foreign films virtually unavailable to moviegoers.” Oprah Winfrey, who once dated Ebert, has credited him with encouraging her to go into syndication with her television show, which ultimately made her a millionaire.

In 1996, on the 20th anniversary of his first show with Siskel, Ebert acknowledged the comparative longevity of his career. “I an aware of no other American newspaper critic who has been continuously at his job longer than I have,” he stated, adding his comment on a phenomenon known to most long-time filmgoers: “When I mentioned Bonnie and Clyde during a talk at the University of Virginia, a student referred to it as an ‘ancient movie’ To me, it seems contemporary. Yet a little math revealed that Bonnie and Clyde is now older than Casablanca was when I began reviewing in 1967.”

Gene Siskel died in 1999, after which Ebert worked with rotating co-hosts in the show, now called Roger Ebert and the Movies. The following year, another Chicago Sun-Times writer, Richard Roeper, became a permanent co-host, and the show, retitled Ebert and Roeper, ran until 2006.

Since the 1970s, Ebert had worked as a guest lecturer for the University of Chicago, teaching night classes and talking candidly about his life, including a battle with alcoholism in the 1970s. The books he authored, besides collected film reviews, included works on the first hundred years of the University of Illinois (An Illinois Century), a fictional thriller (Behind the Phantom’s Mask) and a guidebook, The Perfect London Walk, a tour of his favourite European city. He also compiled two books exclusively featuring his venomously wicked pans of films he disliked.

Ebert, who married a trial lawyer, Chaz Hammelsmith, in 1993, had his first battle with cancer in 2002, when an operation successfully removed papillary thyroid cancer. The following year he had an operation for cancer in his salivary gland, followed by radiation treatment, though through it all he did not miss one new film. In 2006 he had a section of his jawbone removed, then had to be taken to hospital when an artery burst as a side-effect of radiation treatment.

Shortly after, he issued a statement, saying that he believed in “full disclosure” and that doctors were seeking a solution to protect his arteries. He later learned to speak with a voice machine, and in 2010 he appeared on Oprah Winfrey’s talk show with a machine that tailored his speech more closely to his natural voice. In later years, he found the internet a valuable outlet, with millions accessing his website.

In 1996 Ebert spoke of his predilection for working in tandem. “There is always one ready to question a judgement, disagree with an analysis or second an opinion. When Siskel and I agree strongly on the worth of a film, as we have with such films as Pulp Fiction, Hoop Dreams, Leaving Las Vegas, Crumb, Dead Man Walking and Fargo, I believe we can help them to find wider audiences. Do we have ‘too much influence’, as some have said? Given the influence of national advertising campaigns, media junkets, fast-food and T-shirt tie-ins, and mass bookings into 2,000 theatres at a time, I don’t think we have nearly enough influence.”

In 2011 Ebert wrote an autobiography, Life Itself, in which he describes himself as “beneath everything else a fan”. It was hailed as his finest book, and is scheduled to become a film produced by his friend Martin Scorsese. Ebert writes in his memoir, “Kindness covers all my political beliefs. To make others less happy is a crime ... I am grateful for the gifts of intelligence, love, wonder and laughter.”

Roger Ebert, writer: born Urbana, Illinois 18 June 1942; married: 1993 Chaz Hammelsmith (one stepdaughter); died Chicago 4 April 2013.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments