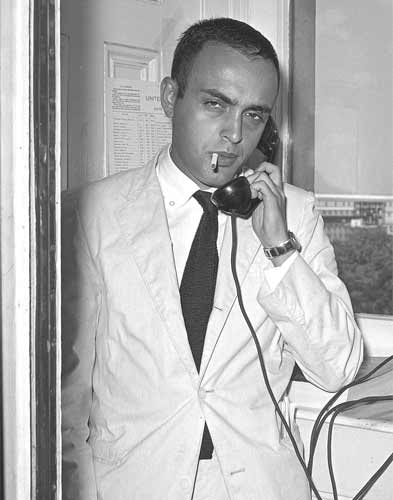

Robert Novak: Influential and pugnaciously conservative political journalist

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Today's top-tier Washington political reporter tends to be smooth and Ivy League, as much a member of the city's establishment as the politicians he writes about. Well before the end of a career that spanned half a century, Bob Novak, too, was a pillar of that establishment. He was one of the most influential journalists in town, whose columns at one point were syndicated in more than 300 newspapers, and whose pugnacious conservatism made him a natural for the shout shows of cable television.

At bottom though, he was an old-fashioned shoe-leather reporter: a small-town boy from the Midwest who had cut his teeth with the Associated Press in Nebraska and Indiana, and who in his own words always was "looking for trouble". And of trouble, Novak found and made plenty – not least with the later column for which he is best remembered, in which he revealed, in July 2003, the name of the CIA operative Valerie Plame.

The CIA-leak imbroglio is too complicated to explain here. But it became one of the most venomous domestic sideshows of the Iraq war, leading ultimately to the conviction of Lewis "Scooter" Libby, the chief of staff of then vice-President Dick Cheney, for lying to a grand jury. The affair dragged on for four years, but Novak, the man who had started it, somehow floated above the fray, even as Judith Miller, a New York Times reporter who had also learnt of Ms Plame's identity, spent three months in jail for refusing to reveal her source.

Only when the dust settled did it emerge that Novak had originally been tipped off not by Libby, but by the former deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage. At Libby's trial, several leading Washington journalists were hauled into the witness box to testify, but to the astonishment and chagrin of many liberals, Novak was not among them.

In reality, the Plame affair was hardly one of Novak's biggest scoops, most of which came in the column he wrote for more than four decades, first in partnership with Roland Evans, and then solo after Evans's retirement in 1993. In its Seventies and Eighties heyday, the "Evans and Novak Report" was a virtual bulletin board for the inner councils and rivalries of the Republican party. But its reach stretched much further. One consequential column was a 1978 interview with Den Xiaoping that helped pave the way for closer US/Chinese relations.

But even that paled beside the 1972 column in which Novak quoted a Democratic senator as saying that George McGovern, the party's presidential nominee, favoured abortion, the legalisation of marijuana and amnesty for those who had refused to fight in Vietnam. Thus was born the "abortion, acid and amnesty" label that effectively doomed McGovern's admittedly slim chances of winning the White House that year. The fact that such explosive charges were attributed only to an unnamed senator led some on the left to accuse Novak of making them up. Only in 2007 did he reveal that his informant had been none other than Thomas Eagleton, named and then dropped by McGovern as his vice-presidential running mate.

Whatever else, that scoop was a perfect illustration of how for Novak, intrigue and skullduggery always counted for more than worthy analysis and editorialising. At bottom he was a reporter, not a commentator. Evans and Novak might have been a basically Republican brand – but that did not prevent them churning out over 120 columns about the Watergate scandal that led to the downfall of a Republican president.

Novak's conservatism, and its tinge of world-weary pessimism, earned him the nickname of the "prince of darkness" (a sobriquet he shared with Richard Perle, Ronald Reagan's hardline arms control adviser). He looked the part, too, when almost daily television appearances made his face as familiar as his byline. With his three-piece dark suits, beetling black eyebrows and toothy leer, Novak epitomised the right-wing bigot who haunts liberal nightmares. And he revelled in the role, happily taking outrageous positions to provoke an argument, and once walking off the CNN set after a particularly angry exchange with his Democratic opponent James Carville.

At that point he decamped to the friendlier ideological environs of Fox News. But he was never afraid to take on the conservative orthodoxy of the hour. In 2001 he dared suggest that America's close alliance with Israel had partly contributed to the 9/11 attacks, and two years later he emerged as one of the first and fiercest conservative critics of the Iraq invasion.

By then however Novak's image was beyond change. Of Lithuanian Jewish upbringing, he converted to Catholicism in 1998 when he was 67, because of what he called a "spiritual hunger". The priest at the ceremony enthused at how the "prince of darkness" had been transformed into "a child of light". At which point Novak's friend, the no less curmudgeonly Democratic Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, is said to have remarked, "Well, now we've made Bob a Catholic, the question is, can we make him a Christian?"

Rupert Cornwell

Robert David Sanders Novak, political journalist: born Joliet, Illinois 26 February 1931; married firstly Rosanna Hall (marriage dissolved), 1962 Geraldine Williams (one son, one daughter); died Washington DC 18 August 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments