Robert F Boyle: Oscar-winning art director who created some of Hitchcock's most memorable settings

Robert Boyle was an Oscar-winning art director whose early architectural training was instrumental in his success.

He worked several times with Norman Jewison, including on the original The Thomas Crown Affair and Fiddler on the Roof, and with Douglas Sirk, and Alfred Hitchcock. For the latter he created some of the most arresting visual images in cinema; on The Birds, he had to work out how to stage the attacks by seagulls on Tippi Hedren; and as part of the art-direction team on North by Northwest, for which he earned the first of four Oscar nominations, he recreated Mount Rushmore for the climactic fight scene.

Robert Boyle was born in Los Angeles in 1909. He graduated from the University of Southern California's School of Architecture in 1933, but could not find work in his field so took a job in Paramount's art department. Transferring to Universal, he was put in charge of the serial Don Winslow of the Navy (1941) and, as associate art director, worked on films including The Wolfman (1941).

In Hitchcock's Saboteur (1942) the hero is pursued across America, and the director's penchant for impressive set pieces in famous locations necessitated recreating the Statue of Liberty – inside and out. Ironically, given its story of fifth columnists, Boyle's wife, Bess, later had her screenwriting career destroyed by the House Un-American Activities Committee. For Shadow of a Doubt (1943), which Hitchcock claimed was his own favourite film, Boyle recreated small-town America.

Boyle's settings ranged from Alaska (Arctic Manhunt, 1949, and Abbott and Costello Lost in Alaska, 1952) to the boxing ring (Iron Man, 1951) and a slew of Westerns. The supernatural portmanteau Flesh and Fantasy (1943) called for some particularly creepy designs, while Lady Godiva of Coventry (1955) obviously did not concern itself too much with historical accuracy.

After a 16-year hiatus, Boyle rejoined Hitchcock for North by Northwest (1959). Apart from recreating Mount Rushmore, they also designed an impressive Frank Lloyd Wright-inspired house for James Mason (though Wright would have avoided the cantilevering, however necessary for the plot). It was achieved with sets and special effects, though the iconic design has led many film fans to hope to visit it.

It was the jolt that Boyle's career needed and he was able to escape some of the workaday assignments that had been his lot. For Cape Fear (1962), the sweaty North Carolina summer was the background for a morally troubling revenge thriller.

For Hitchcock's The Birds (1963) the extensive special effects presented their own problems, while Marnie (1964) is the director's most unashamedly artificial-looking film, epitomised by the shot along the – obviously painted – street where Marnie's mother lives. Boyle later became a regular interviewee in documentaries about these films and their director.

Boyle won two Oscar nominations for his work with Norman Jewison. After The Thrill of It All (1963), he recreated New England in California for the Cold War comedy The Russians Are Coming the Russian's Are Coming (1966). The stylish original version of The Thomas Crown Affair (1968) was followed by Chicago, Chicago (1969), about Ben Hecht's pre-Hollywood life as a reporter. Sadly uninvolving but handsomely mounted, it gained Boyle another Oscar nomination. For his next nod, Boyle could hardly have a more different assignment, with the 19th-century Russia of Fiddler on the Roof (1971) which, after extensive research, was filmed in what was then Yugoslavia.

Boyle's fourth Oscar nomination came with 1976's The Shootist, an autumnal and bittersweet Western starring the dying John Wayne.

In 1979, the star-studded Winter Kills was Boyle's strangest assignment. This presidential-assassination conspiracy black-comedy was written by Richard Condon, author of the similarly themed The Manchurian Candidate. Boyle designed luxurious settings as well as a control centre worthy of a Bond villain. Director William Richert later said of Boyle: "If you could think it, he could do it," while Boyle described the work as "delightful". Funded by drug dealers (one was assassinated part way through production, the other was later arrested), Boyle was sent to mysterious meetings to pick up suitcases of money. Production was shut down more than once, and when it was declared bankrupt, Richert and the film's star, Jeff Bridges, went to Germany to make another film, The American Success Company, to fund the completion two years later. Perhaps it was a cost-saving device that saw Boyle take a cameo as a desk clerk.

North by Northwest was initially called "The Man on Lincoln's Nose" and that was the title of an Oscar-nominated documentary about Boyle in 2000, showing the original designs and photos of him clambering over the Rushmore set.

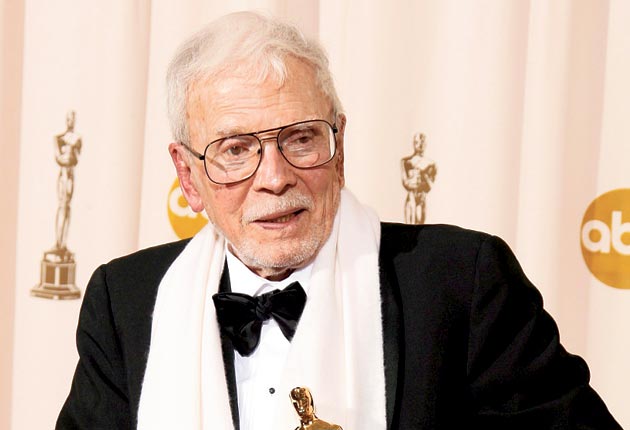

But despite his four nominations Boyle would have to wait until 2008 to receive an honorary Oscar. At 98 he was the oldest recipient of the award. In 1997 the Art Directors' Guild – of which he was a two-term president – awarded him a Lifetime Achievement Award.

After retiring, Boyle lectured at the American Film Institute Conservatory in Los Angeles where he was described by the Art Directors' Guild as its "guiding light".

Robert Francis Boyle, art director: born Los Angeles 10 October 1909; married Bess Taffel Boyle (died 1999; two daughters); died Los Angeles 1 August 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments