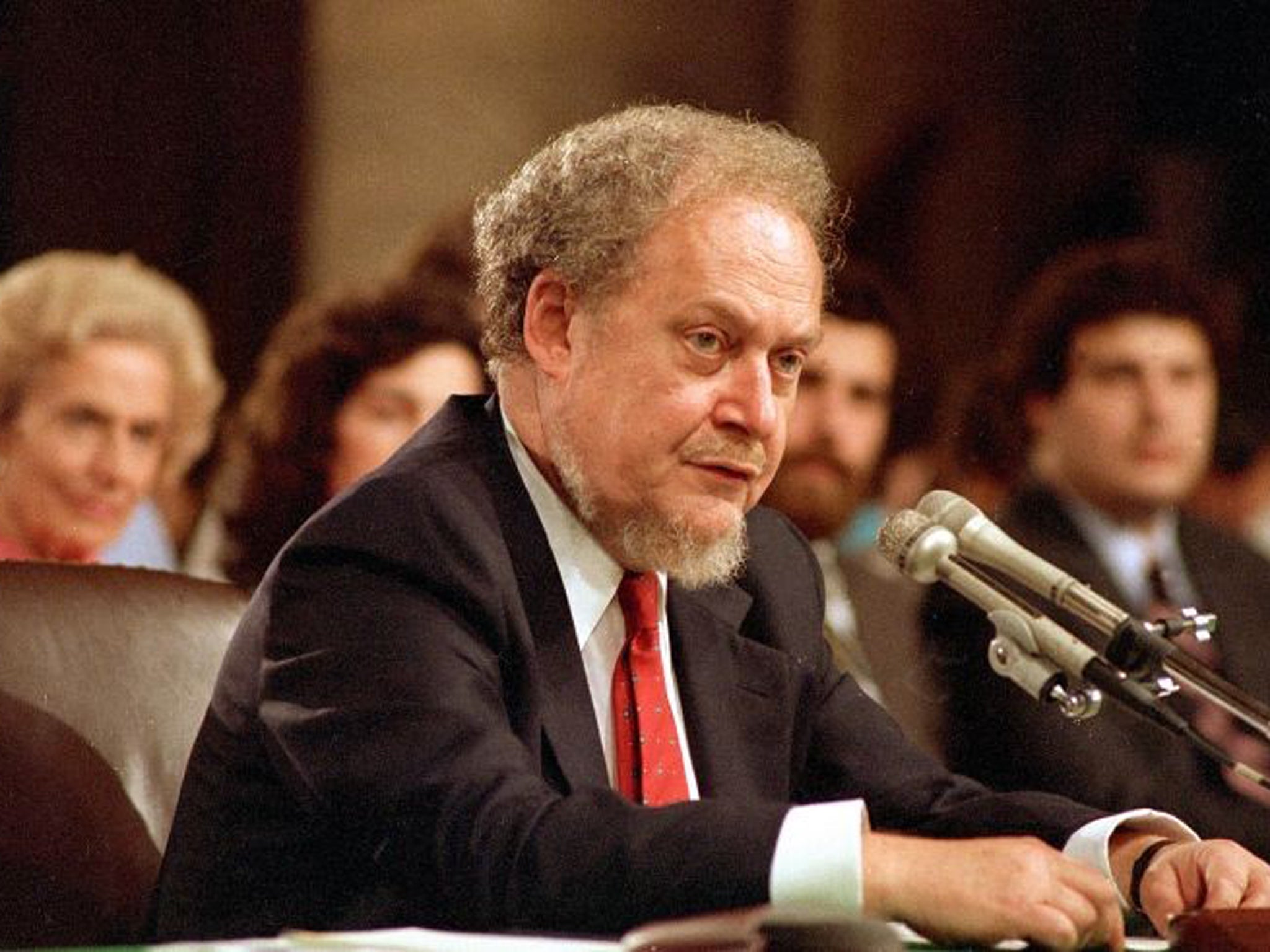

Robert Bork: Jurist who was rejected for the Supreme Court

‘They turned him into a gargoyle, an absolute beast,’ a supporter said of Congress

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Among American conservative jurists, Robert Bork was arguably the most influential of his era. He also had a highly significant cameo role in the Watergate scandal. But he is remembered above all for a failure: his 1987 rejection by the US Senate after he had been nominated by Ronald Reagan to the Supreme Court – an epic struggle whose repercussions are being felt even today.

The stakes could not have been higher. The retirement of the centrist justice Lewis Powell that year had created a vacancy liberals believed might tilt the balance of the high court decisively to the right. Those fears took concrete shape when Reagan named Bork, an outspoken opponent of abortion and affirmative action, as Powell’s successor. Over his qualifications, there was no argument. Bork had been an eminent law professor at Yale for the best part of two decades; he had held high judicial posts in government, and for the previous five years had been a judge on the federal Court of Appeals on the DC circuit, whose prestige was outstripped only by the Supreme Court itself.

But the Democrats who then controlled the Senate (and thus the nomination process) chose battle on the grounds of Bork’s temperament – that he was a extremist whose judgement could not be trusted, whose concerns were not for the ordinary man but for the abstruse rationale of the law, as seen through a rigid right-wing prism. Bork was a strict “originalist” who argued that the constitution was not an evolving entity, but to be interpreted in the light of what its 18th century authors intended its words to mean.

The battle was ferocious, and Bork did little to help his cause. In private he was courteous and warm, but during the televised public hearings he came across as brittle and combative, showing little of the deference expected by his senatorial questioners. The Judiciary Committee, headed by then senator, now vice-president, Joe Biden, voted nine to five against Bork. When the nomination came to the full Senate, it was defeated by 58 to 42.

As rarely before, opponents vilified the nominee in the media and on the floor of Congress: “they turned him into a gargoyle, an absolute beast,” said Alan Simpson, the Republican Senator from Wyoming who was a strong Bork supporter. Such brutal treatment became known as “borking”, thus adding a new word to the American political lexicon. “My name became a verb,” the victim said years later, “and I regard that as one form of immortality.”

Bork’s conservatism was born during his days at the University of Chicago law school, hardened in the Marine Corps during the Korean war, and polished during his two spells as a professor at Yale Law School, between 1962 and 1975, and 1977 and 1981, where his pupils included Bill and Hillary Clinton.

In those years he established his reputation, not just as a fervent opponent of abortion and gay rights, two of the main social movements of the day, but also as a greatly respected theorist on anti-trust issues, with his argument that the chief purpose of legislation should be to protect not small companies, but the interests of the consumer.

Such views made him a natural Republican, and in mid-1973 Bork became President Richard Nixon’s solicitor-general, the government’s representative before the Supreme Court. By then the Watergate scandal had achieved critical mass.

On 22 October 1973 an exasperated Nixon told attorney general Elliot Richardson to sack his tormentor, Watergate special prosecutor Archibald Cox. Richardson refused and resigned, as did his deputy William Ruckelshaus. Bork became acting attorney-general, and carried out Nixon’s order. The “Saturday Night Massacre” was an event that for many sealed Nixon’s guilt, even before the Watergate tapes became public the following year and forced the president’s own resignation.

Bork stayed on as solicitor-general until the end of the Ford administration, when he returned to Yale. But after the death of his first wife he went back to Washington, as a Reagan appointee to the DC Court of Appeals. In 1986, he was considered for the high court seat that was eventually filled by Antonin Scalia (and who remains the loudest conservative voice on the current Court). In 1987 he was nominated, with fateful consequences.

The rejection deeply affected Bork, turning him further against a system in which, he said, “the tactics and techniques of national political campaigns have been unleashed on the process of confirming judges. That is not simply disturbing. It is dangerous.” Ever more vociferously, he railed against left-wing judicial activism that, in his view, sought to substitute courts for elected politicians.

The very titles of various books Bork published in subsequent years summed up his views. The Tempting of America: The Political Seduction of the Law, which appeared in 1989, was followed by Slouching Toward Gomorrah: Modern Liberalism and American Decline, also a best seller, arguing that egalitarianism and other liberal causes were against natural law, and finally in 2005 by A Country I Do Not Recognize: The Legal Assault On American Values.

Even after that Bork continued his involvement in politics, serving as a senior advisor on legal issues to Mitt Romney during the latter’s unsuccessful 2012 presidential campaign. But the repercussions of what happened to him as a Supreme Court nominee have been even longer lasting.

Contentious confirmation hearings for judges have become, and will surely remain, the norm. Republicans now are as competent at “borking” opponents as Democrats. Chastened by Bork’s experience, the conservative movement has become more disciplined, less inclined to shoot from the hip, more adept at disguising its beliefs. Hence the “compassionate conservatism” peddled by the most recent President Bush in his 2000 election campaign – not to mention the inscrutability of every conservative nominated to the highest court in the land.

Robert Heron Bork, jurist and government official: born Pittsburgh 1 March 1927; married twice (three children); US Solicitor General 1973-1977; Acting US Attorney General October-December 1973; judge, DC Court of Appeals 1982-88; nominee for US Supreme Court 1987; died Arlington, Virginia 19 December 2012.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments