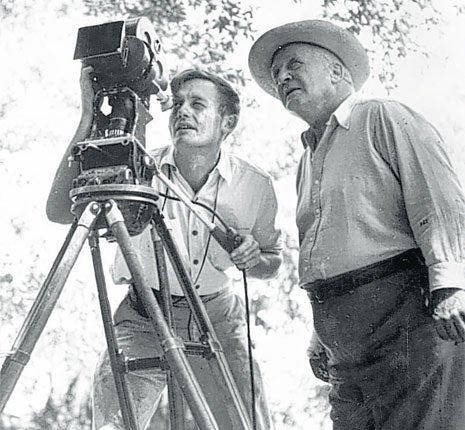

Richard Leacock: Documentary film-maker regarded as the godfather of 'Direct Cinema'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Richard Leacock was a pivotal figure in the development of the documentary film. He connects Robert Flaherty, conventionally the first film documentarist, to today's "fly-on-the-wall" digital practitioners.

Leacock, who was known as "Ricky", was the cinematographer on Flaherty's last feature, Louisiana Story (1948), where his skills as one of the cinema's greatest camera operators were deployed in the service of romanticising the benefits of oil exploration: the film was paid for by an oil company. It was not, however, the moral difficulties of such sponsorship which were to drive Leacock. He was frustrated by the endless interventions and reconstructions filming entailed, especially when shooting synchronous sound.

Flaherty had discovered the trick of turning footage of ordinary people going about their everyday lives into absorbing dramatic stories – the essence of documentary – with Nanook of the North (1922). Leacock, though, came to believe there was precious little of ordinariness – truth, really – left when the film-making was done. He was always a man of strong opinions, and documentaries, he felt, were in danger of becoming nothing more than records of what people did when being filmed, not pictures of how they behaved normally. What was needed was equipment which would allow the film-maker to capture scenes with far less intervention than was then usual.

His quest for technology better able to fulfil documentary's promise first reached fruition with Primary, a study of Senator John Kennedy's 1960 run for the Democratic presidential nomination. The multiple crew assembled for this film – DA Pennebaker, the Maysles Brothers, Terry McCartney-Filgate (on loan from the National Film Board of Canada) overseen by Time-Life journalist Robert Drew - were to spearhead a documentary film-making revolution. What are now clichés – behind-the-scenes shots of a political campaign – were then startling, fresh and unprecedentedly intimate.

Leacock was the senior figure, both by virtue of his age and Louisiana Story's Oscar nomination. Operating the prototype portable sync sound rig, he famously filmed Kennedy pacing his hotel room listening to the election results with an unobtrusive camera resting on the arm of his chair. There were no extra lights, no tripod, no personal microphones; and, it would seem, no awareness of the camera on the part of the people being filmed.

The event was far more important than the filming, and letting events, even less exceptional and exciting ones than this, always be more important was Leacock's prime intention. This style of observational documentary was to be characterised by long, uninterrupted takes using hand-held cameras, available lights and directional mics. Beyond obtaining permission to film, there were to be no set-ups, no interviews, no added sounds. These rules, largely first articulated by Leacock, were to become the dogma underpinning "Direct Cinema".

Richard Leacock was born in London in 1921 to a family descended from 16th century French Huguenot refugees. He was raised on the Canary Islands, where his communist father owned a banana plantation. Leacock was educated at Bedales and Dartington Hall, schools unconventional enough to be exposing their students, in 1930s, to, among other things, Russian revolutionary documentaries. He was inspired to take up the expensive hobby of 16mm film-making.

His first finished work, at 14, was Canary Bananas. This poetic impression of his home was made to convey to his schoolmates, who were intrigued by his exotic background, an impression of where he came from: to give them, in his phrase, "the feeling of being there". His biology master had also taken him when he was 17 to film an expedition to the Galapagos.

Among his schoolmates were Flaherty's daughters. Leacock screened Canary Bananas for Flaherty when he was visiting the school and Flaherty promised that they would work together someday. Leacock studied physics at Harvard, but was interrupted by the Second World War, in which he served as a US Army cinematographer. Flaherty kept his promise when he hired him to be the cinematographer on Louisiana Story.

Both on that film and subsequently as a successful maker of sponsored documentaries in the 1950s, Leacock became increasing frustrated at the cumbersomeness of the process,especially when shooting sync. He started hand-holding totally unergonomic 35mm stand cameras. It was one of these experiments, Toby and the Tall Corn (1954), that caught Robert Drew's attention. Out of this came the collaboration that produced Primary and the first wave of "Direct Cinema" classics for the ABC television network in America.

Leacock was a life-long enthusiast for the machinery of image capture. He had complete technical mastery of the equipment – he could maintain any of the cameras with which he worked. His main contribution to the standard documentary film-making outfit, which dominated production from the early 1960s until the coming of broadcast-standard portable video in the 1990s, was the wireless control mechanism. This allowed camera and tape recorder to be run in sync, using a crystal oscillator Leacock liberated from a Bulova electronic watch.

Leacock, though, was more than a brilliant camera operator fixated on the gear. Watching his oeuvre, one feels he never filmed anybody he did not come to like – small-time police chiefs wondering whether their town councils would stand for them buying some bazookas; fundamentalist Christians who spent their Sunday mornings vomiting up the devil; deranged Indianapolis race-car drivers. In Happy Mother's Day (1963), a film about the cavortings surrounding the birth of quintuplets in a small mid-Western town, Leacock's camera becomes the somewhat bemused mother's conspirator in observing the shenanigans. Unlike many of his peers, his eye was never cynical.

Although he never stopped his own film-making, in 1968 Leacock accepted an invitation to join the then recently established MIT film production programme. He taught there for the next 20 years, producing a whole school of observational film-makers.

On retirement, he lived in Paris with his partner Valerie Lalonde, who survives him. He is also survived by five children from two dissolved marriages and nine grandchildren.

Brian Winston

Richard Leacock, documentary filmmaker and educator: born London 18 July 1921; Professor, Massachusetts Institute of Technology 1968-88); married twice (divorced twice; five children); died Paris 23 March 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments